Forever Young: The Story of Rebecca Pelkey, Part Two

This is the second of a two part series. Click here for part one.

Laying Becky Pelkey to rest

On the afternoon of Monday, November 14th, 1988, 5 days after 14-year-old Rebecca Pelkey’s body was discovered in the rural Maine woods, family and friends gathered at Brookings-Smith Funeral Home in Bangor to memorialize her life. The pastor from a nearby Baptist church led the ceremony. Becky was dressed in her blue prom dress. After the service, everyone headed to South Levant Cemetery for Becky’s interment, just five miles away from the spot in where her body was found. It was a cool and cloudy fall day—temps in the 40’s—and everyone’s hearts were heavy from the sudden loss of Heather’s eldest child, Rebecca Sue Pelkey. The inscription on her headstone read, “We love you” and “We miss you” and it was signed by her siblings and her mom.

Family fractured by the loss

Her cousin, Kristina, remembered that it changed her family forever.

Kristina: “I do remember that being a turning point of the family as a whole. It was a heavy vibe around the home. Heather and the children were there a lot. I specifically remember my dad spiraled into a depression—also Heather, obviously. Substance use became a more daily, prevalent, issue. My dad would play the piano when he was sad, so I remember this sad piano music.”

8 years after Becky’s death, her younger brother, JR, died in a tragic accident working on a car. He was just 18 years old.

Kristina: “Becky’s brother, JR, passed away from an unfortunate accident. And then, a year after that, her other brother [died by] suicide on Becky and JR’s graves. And my dad discovered his body.”

By 1997, three of Heather’s four children had died: one by murder, one by suicide, and one by accident. She had only one surviving daughter—the youngest of the four—who was just 3 years old when her older sister was killed. Heather’s fraternal twin brother, Kirk, took it very hard.

Kristina: “He took a lot of responsibility for that... that he wasn’t able to protect her, or find her. He carried this heavy burden. Anything related to Heather or her kids was his responsibility. I think that he internalized that. It definitely still weighs on him today. He’s very quick to get upset when discussing it or Heather or any of the kids.”

Becky’s autopsy

The day after her body was found, a group of men, all employed by the state of Maine, gathered in a well-lit room in Augusta to study Becky’s remains—to learn what they could about her death and document their findings. There were three members of the Maine State Police present, a prosecutor from the Attorney General’s Office, and two medical examiners. Ronald P. Roy, Deputy Chief Medical Examiner, took the lead in performing Becky’s autopsy. It began at just after noon on Thursday.

Her body had been stored and transported in a “plastic body pouch,” which they carefully removed. An ID tag with her body said “unidentified white female”—though Becky was Native American and by this point on Thursday had been identified. Her blue jean-jacket had been pulled over her head to the front of the body and her arms were still trapped in the sleeves. The field team had carefully put her hands and feet in paper bags to limit their disturbance and preserve trace forensic evidence. After disentangling her from her jacket and removing the bags, they could see her black 80’s T-shirt, which had an emblem on the front and said, “Bad to the Bone.” They checked the pockets of her jacket and found them all empty except for the left front breast pocket, which had an unopened package of Black Cat fireworks.

Though her body had likely been sitting in the woods for a week, it was in good condition.

An examination of her fingernails showed no obvious blood or foreign matter under them. Still, they were clipped and bagged as evidence. They carefully searched her for loose hairs and fibers and though they found several of her own hairs and even some animal hairs, they also found a light-colored short curly hair that appeared to be a pubic hair on the right shoulder of her T-shirt.

There was a skinny white nylon rope wrapped around her neck many times and pulled taut. Its diameter was only about a quarter of an inch. Part of the collar of her T-shirt was trapped in the loops and so was her hair. As it was unwound from her neck, Dr. Roy discovered that it was looped underneath itself, which he carefully undid. When he got to the final loop around her neck, he found that the length of the rope terminated in a tight knot, so he cut it off of her.

There were impressions left on her skin from the rope—it was what Dr. Roy ultimately ruled was the cause of her death—asphyxiation by ligature strangulation. There was also what looked to be a shoe print on the left side of her face and neck. Dr. Roy noted bruising in the areas near the shoe print.

Her T-shirt was removed which revealed that her mauve bra—which she was still wearing—had been pushed up above her breasts. There was plant and soil debris on the front and the back of her abdomen below the breasts.

She was bottomless—she had been discovered with her blue jeans carefully folded and placed over her genital area. Through a search of the surrounding woods, police were able to recover her panties.

Dr. Roy took sample swabs from her genitals and her mouth and turned them over to the state police for testing, but noted that there was “no evidence of trauma” to her sexual organs.

After the surface-level observations, he made some incisions to see what could be learned through an examination of her internal organs. Her stomach contained a large quantity of slightly-digested food including thinly sliced light-green pickle, tomato, hamburger, and light green lettuce. All of the organs looked normal. She was a healthy young girl.

After recovering some fluid from near the heart, he ordered a drug and alcohol toxicology screening. The results came back positive for alcohol.

After they concluded their solemn task, they cleaned things up and turned the body over to Brookings Smith, the funeral home in Bangor that would handle her funeral arrangements.

Key information released

A week later the Maine State Police released the cause of death to the press. They also revealed that they believed that Becky was killed where she was found dispelling the notion that her body was merely dumped there.

Charges are brought

Other than a sweet thank-you note for the support, flowers, and cards that was published by Becky’s family in the Bangor Daily News, there was no update on the case for several weeks until an explosive day in early December.

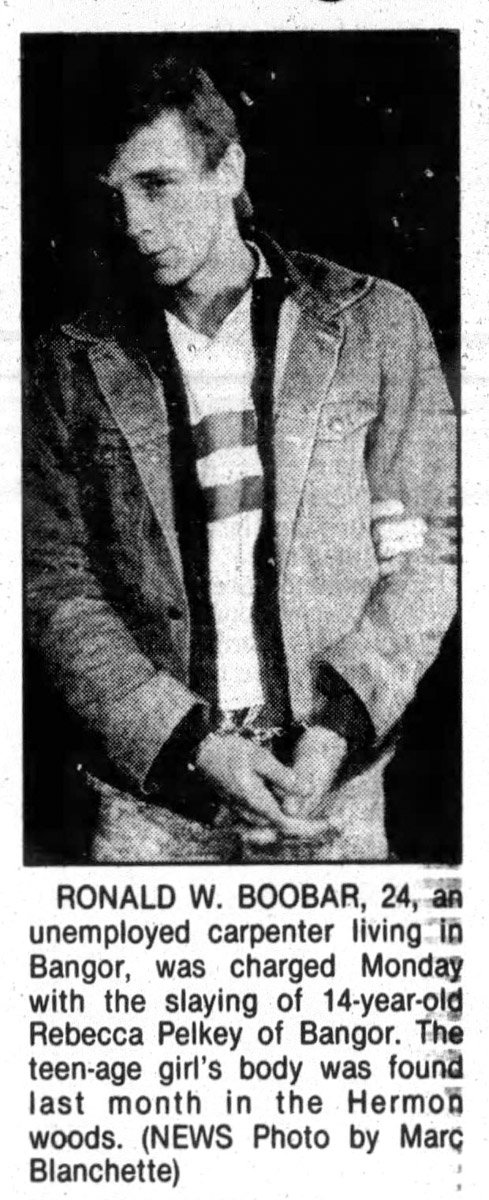

At 5:00PM on Monday, December 5th, a month after her body was found, a prosecutor for the attorney general presented the facts and evidence to a secret grand jury to indict Ronald Boobar of murder. They agreed, and Ron was arrested at 6:00PM at his apartment on Union Street in Bangor. As he was being led to a waiting police car, he told reporters that he did not kill her and didn’t know who did. Detectives told the press that crucial testing results from forensic evidence had come in just days prior leading to the arrest.

Two days later, Ron was arraigned, and he pled not guilty. Ron told the court he couldn’t afford an attorney. After filling out some paperwork, the judge agreed and assigned him a public defender: attorney John Hilary Billings. John also represented a defendant in another case we covered: James Hicks (link).

As he was leaving the courthouse, Ron spoke freely to reporters again, saying, he “was in the wrong place at the wrong time,” and that he had both an alibi and witnesses. He said that he had dropped “the girl” off in Bangor a week before she was found and had no idea who killed her.

Ron fights for freedom

The judge held Ron without bail after the arraignment, and there was another hearing, a week later, to determine whether or not to grant him bail. Ron’s family—his mom and dad, his aunt and uncle, and his grandfather—rallied behind him in the pews of Penobscot County Superior Court. Ron’s attorney offered up a number of bail conditions that Ron was willing to submit to: staying in the custody of his parents, checking in daily with the Bangor Police Department, observing a nightly curfew, abstaining from alcohol... even staying at jail nightly so that he could continue to work during the day to support his wife and future child. She was in a difficult spot as his landlord had recently evicted them. John said that in just a few short weeks—on Christmas Eve—she was due to give birth, and asked for grace from the court. Ron’s family estimated that they could come up with $8,000 as collateral to secure Ron’s release.

But the judge ruled for the state and denied him bail because of the seriousness of the offense and the evidence against Ron, which was substantial, so Ron was held in jail until trial.

His attorney appealed the judge’s decision and got an audience with the Maine Supreme Court a week later. They upheld the decision and Ron was out of options.

Ron’s attorney fires him

His attorney sought to have a key document—the summary of evidence from Detective Zamboni of the Maine State Police—made secret. By default, after a detective’s affidavit is filed with the court, it will become a public record. John wanted to keep Ron from being tried in the court of public opinion, and to reduce the difficulty of finding a jury who had no preconceived notions about Ron’s guilt or innocence. The state expressed no opinion either way and the judge agreed, impounding it for one-month periods (which were extended several times).

Soon after Ron was charged, the prosecutor turned over to him and his attorney all of the evidence that they had against him—known as “discovery.” His defense attorney got money from the court to hire experts and a private investigator to look into alternative suspects.

About three months into this process, Ron’s attorney fired him, saying, “Such deliberate, unilateral conduct contrary to the expressed counsel... has led to an irretrievable breakdown in our relationship.”

He was talking about Ron leaking all of the discovery documents to the press. WABI-Bangor was doing nightly TV news reports on it, and John was furious. He had had it with Ron. He filed a motion to withdraw as his attorney to the court, and it was approved. So Ron got a new attorney: Martha Harris.

March 1990 - Trial begins... Or does it?

On March 12, 1990, one year and four months after Becky was murdered, jury selection began. From a pool of 112 potential jurors, 90 were dismissed due to them having a “more than basic knowledge” of the case or knowing potential witnesses, leaving them with just 22. Their goal was to find 47. By the next day they had their jury, but before trial could begin, the attorneys needed to have an evidentiary hearing about a key prosecution witness: Daniel DesIsles.

He was an Alcoholics Anonymous coordinator and knew Ron from before he was an alleged murderer. He handled all of the AA meetings for the Penobscot County Jail, and conducted a couple of telephone sessions with Ron while he was incarcerated. When he took the stand, he testified that Ron had told him twice that he had killed Becky. He said that it took him 10 days before he came forward to officials with his statement because he was grappling with a moral conundrum: was he breaking the code of confidentiality of AA?

Ron’s defense attorney immediately objected and moved to suppress the testimony, claiming that whatever Ron had said to him was protected by law as privileged communication. She later supported her argument with a memorandum that explained although she couldn’t find any case examples dealing with AA specifically, by analogy, there were other similar communications protected by statute: lawyer-client, therapist-patient, husband-wife, and pastor-parishioner. Martha added, again, by analogy, that any information that inmates shared with counselors working in a jail by law couldn’t be used as evidence. But Daniel was not a licensed counselor—he was a volunteer for AA. Daniel said that Ron had crossed a line and that he had a moral duty to disclose the confession.

Regardless of the legality of the testimony, the public was simply interested in the truth, and this was an explosive revelation: Ron had confessed to the murder in a private one-on-one conversation with someone he trusted.

The judge ruled that the testimony would be admissible because there was no statute protecting the conversation—regardless of its similarity to other types of protected speech.

The next day, in a bold move, Martha moved to stop the trial, claiming that there was crucial new information that came up during the first days of jury selection that she needed time to follow up on. She requested that the trial be continued to a later date. Despite the fact that the jury was already empaneled, the judge granted the request and moved the trial back three months—to June—and dismissed the jury.

Trial is moved!

After the trial’s false start, the release of Zamboni’s affidavit, and the release of the discovery materials, the press was armed with a lot of information about the prosecution’s case against Ron, and they presented it to the public. Martha felt like Ron was unlikely to get a fair trial in Penobscot County because she thought many people might already be convinced of his guilt. Martha filed a motion on Friday, March 16th—the same week the trial had been postponed—and asked for the trial to be moved to a different county in Maine. She explained that one of the defense witnesses, after hearing about Ron’s alleged confession, withdrew their support.

The judge approved the motion and moved the case from Penobscot to Somerset County, where the trial would be conducted in superior court in Skowhegan.

June 1990 - Ron stands trial

On June 11th, 1990, jury selection began, and by the end of the day the lawyers had selected 10 men and 4 women to make up the jury—that’s 12 jurors with 2 alternates.

Over the following 8 days, the trial was conducted. The defense had a list of 39 potential witnesses, and there were 35 for the prosecution. The prosecution had 94 evidence exhibits, and the defense 11. They played the full 3+ hour interrogation recording in the courtroom. It was extensive.

One of the first things that the prosecution sought to establish was the time of Becky’s death. The medical examiner who conducted the autopsy estimated her time of death as 5 to 10 days prior to when her body was found. And the 6-and-a-half-day period that they suggested was accurate fell right within that timeline. Martha presented her own expert witness, Dr. George Curtis, who said he believed she had been dead for only two to five days, likely 3 or 4, which didn’t jive with the prosecution’s timeline. He said that her body was not experiencing certain stages of decomposition that would typically be present—even under morgue refrigeration—if she had been dead for as long as the prosecution said. The attorney for the state, later, in closing arguments, contextualized this medical discussion, saying, quote, “both doctors acknowledged that there’s no real precision in trying to date the time of death. It’s simply an educated guess.”

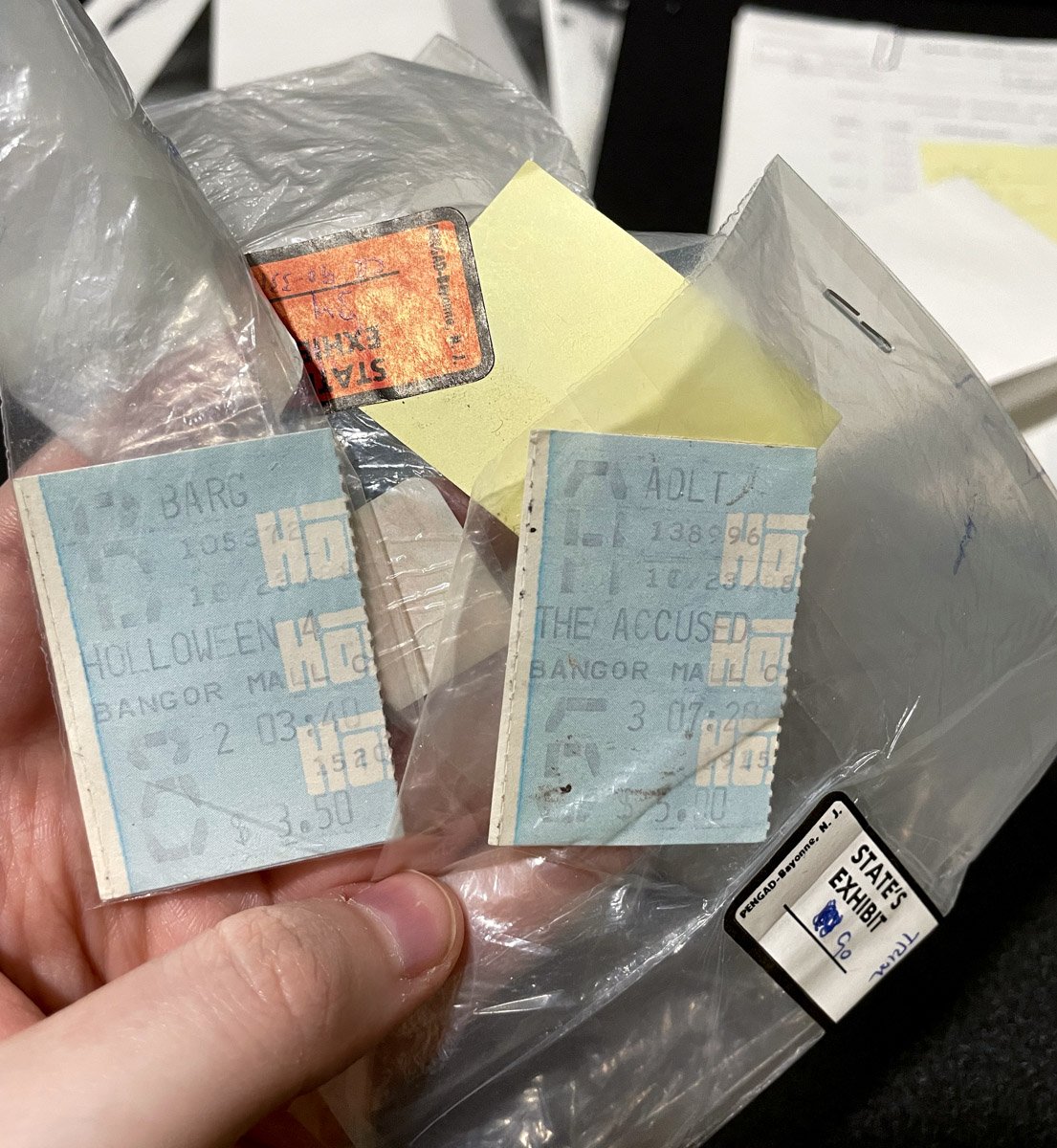

Another factor that pointed to Becky’s death occurring on the night of November 2nd was the contents of her stomach. The autopsy revealed that she had recently eaten a hamburger with pickle, tomato, and lettuce. This was consistent with what both Ron and her friends testified that she had eaten that night. From the interrogation, Ron himself explained that they first went to McDonald’s, but thought it was too expensive, and instead went to Burger King together. The defense argued that fast food hamburgers were a regular part of Becky’s diet and did little to establish her time of death. The presence of alcohol in her toxicology screening, too, was consistent with what happened that evening. Everyone in the car said that they had gone to the liquor store to pick up some vodka and made screwdrivers with it. One other point the prosecution made was that Ron had admitted that the firecrackers found in Becky’s pocket were his. He gave them to her that night.

But most important of all to establishing her time of death was that no one in Becky’s life heard from her after that evening. Where did she sleep that night if she were alive? Her mom hadn’t heard from her, nor any of her friends. Further reinforcing the time of her disappearance was the fact that even though she had made plans with her friends to meet back up at the Bangor Arcade the next day, neither she nor Ron appeared.

The prosecution then sought to place Ron with Becky near the time of her death. Ron himself said that Becky was the last person in the car with him—which was corroborated by the other occupants of the car: Ron’s friend, Scott, and Becky’s friends, Erica and Melanie. He also said during their drive that evening that he was going to take Becky out to Levant to let her try driving his station wagon. Levant is northwest of Bangor, in the same general area where Becky’s body was found. Her body was found in Hermon, technically, but it was just 1 mile from the town line of Levant. The prosecutor also established that Ron had a more than passing familiarity with the area since his wife’s mother lived there. Though Ron didn’t testify at trial, he did insist in his interrogation that he never ended up going out to the country to drive with Becky that night, and dropped her off in downtown Bangor.

The next topic was Ron’s sexual interest in Becky. There was the fact—on its face—that Ron was 24 years old and Becky was an attractive—and older-looking—14-year-old girl. Ron had isolated Becky from her friends, deciding to drop her off last. Both of Becky’s girlfriends said that they saw Ron and Becky holding hands during the car ride. And finally there was the evidence from the scene and Becky’s body, which established that she had recently had sex—pubic hairs and semen were recovered. This, combined with Ron’s history of alcohol abuse and his admission that he was drinking that night, painted a picture of a sexually-motivated crime that was fueled by intoxication.

Ron went to two AA meetings the following day: one around noon and another that evening. The defense suggested it was a man simply seeking help for his addiction and that the timing was merely coincidental. Ron, in the interrogation, said that he had “fallen off the wagon” (of sobriety) again and the night that he went out with the girls, was in the final stages of tapering off his alcohol use before getting clean again. The prosecutor said—here was a man, wracked by guilt, who realized he had crossed a terrible line and was trying to get his life back under control.

The next topic was the damage to the trees and rocks near the site of the murder. The cops said that there were two rocks on the tote road that were scraped by the underside of a car. Ron said in his interrogation that he had recently had some damage to the bottom of his car—specifically the oil pan. He said that it had come from a time that he took the station wagon to a construction jobsite he was working on—a camp up in Lincoln—and that he had gotten it repaired five days after seeing Becky. The prosecutor emphasized the suspicious timing to the jury. Detectives asked him, in the interrogation, if he had told his wife about the damage. After all, the station wagon was titled in her name. He said he had told her... but then he hesitated... stumbled... and eventually claimed that he couldn’t remember when he had told her about the recent damage. There was some bluster in the interview about being able to forensically link the damage to the rocks to the damage to the car, but the microscopic comparison of the paint chips recovered from the trees and the vegetation recovered from Ron’s car was inconclusive. The black color, however, did match the color of Ron’s side-view mirror. The police took Ron’s vehicle out to the site and filmed a recreation, which was shown to the jury. They showed how it would have been possible for the station wagon to make the gouges in the tree and the scrapes in the rocks. The height of his side-view mirror aligned closely with the damage to the trees. Martha criticized the demonstration as unscientific and even called an engineer to the stand who refuted the demonstration, saying that it proved nothing. The prosecutor said that though it was not scientific, it was “suggestive.”

From there they moved onto the hairs that were found at the scene. In addition to the one that was found on Becky’s shirt, there were many other hairs that were found on or around her body. Those hairs were examined under a microscope and compared to hair collected from Ron at the interrogation. A Maine State Crime Lab forensic chemist said that they were “microscopically similar,” but she could not be certain that they were his hairs.

The detectives, during the interrogation, asked Ron about his shoes several times. They wanted to know what shoes he had worn the night he was out with Becky. He said that although he wasn’t sure, it could have only been one of two pair: some work boots or some black sneakers. They asked if they could have permission from Ron to take them as evidence, and he agreed, somewhat reluctantly, because he said it would only leave him with a pair of cowboy boots for his daily use. They then asked him if he had any white sneakers, and he recalled (suddenly) that he had three pair. The reason they were so interested is because Becky’s neck and face had some shoe-prints that looked like basketball shoe tread and some of the other witnesses had remembered him in white high-top basketball sneakers. They also remembered Ron walking on the hood and roof of his station wagon that night, and when detectives processed his car—9 days later—they found shoeprints on the exterior. They took photos and compared them to his white sneakers, and they were a match, which reinforced the theory that he had been wearing them the night of Becky’s disappearance.

The detectives had created an impression from Ron’s shoes and traced the tread pattern left on Becky’s skin onto a transparency and compared it for the jury. The prosecutor claimed that the tread was identical. The defense questioned the techniques that led to his conclusion, again, calling it unscientific, and said that other factors—such as whether the skin was pinched or stretched taut beneath the sneaker—would affect the impression. (To see an image of this exhibit and other images from the case, visit our website, murdershetold.com).

But the prosecution had saved their best evidence for last. They brought four witnesses to the stand—all of whom had direct interactions with Ron and testified as to what he told them.

Daniel DesIsles, the Alcoholics Anonymous coordinator for the jail, testified that Ron—the day after his arrest, during a one-on-one session—had told him twice that he had killed Becky and that only he and one other person knew that he had done it. Daniel said that he had even warned Ron prior to their meeting that they shouldn’t talk about the case, but Ron was undeterred. The next witness was Joseph, who Ronald had carpooled with to an AA meeting in Millinocket about a week after Becky’s body was discovered. Joseph told the court that Ron said he had “cleaned his car of evidence,” and that he had, quote, “gone parking” with Becky the night of her disappearance, lending credence to the sexual motivation theory. The next witness was Charles Kimball, who shared a cell with Ron in jail. He said that he had overheard Ron talking on the telephone saying “I didn’t mean to do it. I just kind of, like, blacked out. I was drunk and stuff.” He said that Ron had told him directly that Becky and he “went parking” and began arguing. Last was Richard Everett, another inmate at Penobscot County Jail. He said that in January of 1989, about a month after Ron was arrested, he was playing cards with Ron and several other inmates. “Somebody asked him if he killed Rebecca Pelkey and he just come outright and said, casual as can be, ‘Yes, he did.’” Richard knew Becky personally, because he had given her a ride one time when she and a friend were hitchhiking between Bangor and Hermon. He remembered her saying that she wanted to go, first to New York, and then to Arizona, where her biological father lived.

The defense tried to impeach the testimony of the four men, one-by-one, by attacking their credibility. For example, Richard, the man he was playing cards with, took a year before coming forward with his account. Why the long wait? She further suggested that Ron had only admitted to the murder at the jailhouse to try and be perceived as tough.

The prosecution had finished, and the defense had the opportunity to present witnesses. Martha called Ron’s mother, who tearfully recalled how Ron had brought his family together to tell them that he was a suspect in the case. “He started crying, and he said he was innocent, that he didn’t do it.”

She called Ron’s father, who helped to establish some of the damage that had happened to Ron’s station wagon.

But most of all, Ron’s greatest defense was his complete cooperation with the investigation. He agreed to be interviewed by investigators immediately. He stayed with them for four hours in the middle of the night, answering all of their questions. He submitted hair samples and blood samples. He gave them permission to search his cars, take his shoes. He agreed to take a polygraph examination. He said that he had confessed to previous crimes that related to the theft and found that he liked jail. And throughout it all, he remained steadfast in his denial. His story, from which he never swayed, was that “Becky was alive and talking and healthy when he dropped her off in front of the arcade around 9:15 or 9:30PM.”

After closing arguments, which summarized the case, the judge gave the jury instructions. He explained that in addition to the murder charge that the prosecution presented, they could also find Ron guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter.

On Thursday, June 21st, at 4:00PM, the case was turned over to the jury. At about 5:30PM, they asked to hear a portion of Ron’s interrogation. It was given to them, but they were told that they had to listen to it in its entirety. As it got into the evening hours, the jury was sequestered at a local hotel and they picked it up again the next morning. At 11:45AM, they returned to the courtroom with a verdict.

The judge asked the foreman if they had reached a unanimous decision. He said that they had.

The foreman read for the court, “We, the jury, find the defendant... Guilty of murder.”

When the decision was shared, Ronald stared straight ahead, showing no emotion. His mother, friends, and other family members sobbed once it had been read.

Sentencing gives a glimpse into Ron’s life

The next step was sentencing, but there would be a thorough pre-sentencing investigation before the hearing which would take months.

Immediately following the conviction, Somerset County started billing Penobscot County for the cost of housing Ron, and there was an argument in the news about who was responsible for paying for his incarceration and other related costs—including medical bills.

For five months a series of psychological tests and interviews were conducted until finally, in November of 1990, right around Thanksgiving, Ron was scheduled to appear in court. His attorney met with him the morning of the hearing and said that he was neither capable of understanding her nor would be able to grasp the impending proceedings because he was doped up on a, quote, “big spread of tranquilizers” that he was given by a jail physician. The judge agreed to continue the hearing and they reconvened in mid-December.

There were a number of letters that were written in support of Ron from his friends and family. His mom didn’t attend the sentencing, on, quote, “the advice of her therapist,” and her letter (which was also signed by his father) seemed strangely irrelevant to the matter at hand. She clarified that he wasn’t responsible for a house fire that had happened 20 years prior, when Ron would have been just 6 years old—rather it was due to faulty electrical wiring. And she also clarified that he had a normal—not contentious—relationship with his sister. Odd.

Ron’s Aunt, whom he spent a great deal of time with, said she knew him very well. He was always well-behaved and brought a lot of joy to their lives. She said he was anxious to please and to be loved. A childhood friend’s mother said that he got along well with his peers.

But the most personal letter was from sister, Susie. She said that Ron was a bit of a loner. He never had a best friend. She found it difficult to believe he could physically harm someone. She recalled times from their youth when he would get into fights with other boys (because of his mouth), but he would never fight back. She acknowledged the times that he had been in trouble with the law for breaking-in, stealing, and forgery, but insisted that none of his crimes were violent.

Susie wrote, “To sum this up, if you would have come to me and told me that Ron robbed a gas station or even a bank, I would have believed it. But as far as him hurting—let alone killing—another human being... it’s just something he’s not capable of. I’m not saying this just because he’s my brother. If I thought for a moment he could have done this, I would want justice done and him to get help. But to me, this is something he did not do.”

Ron told the judge, “I'm no angel. I'm far from it. I made a lot of stupid mistakes, but one of them is not murder.”

Becky’s family spoke at the hearing as well. Her father wasn’t present, but her mom, Heather, said, “My hatred lives inside for Ronald Boobar—who took Becky away from me. The pain of losing my daughter is really beyond words to phrase.”

The prosecutor said that Ron had “nearly committed a crime that was unsolvable” by leaving her body in the woods, where winter weather, animals, and decomposition would have erased evidence. Had those fir-tippers not discovered it so promptly, perhaps Ron would have never been held accountable.

The Pelkey family urged the court to consider a life sentence, but the law said that it could only be applied in certain circumstances—such as the killing of a police officer, a multiple homicide, or in the case of torture.

The judge sentenced Ron to 60 years in prison.

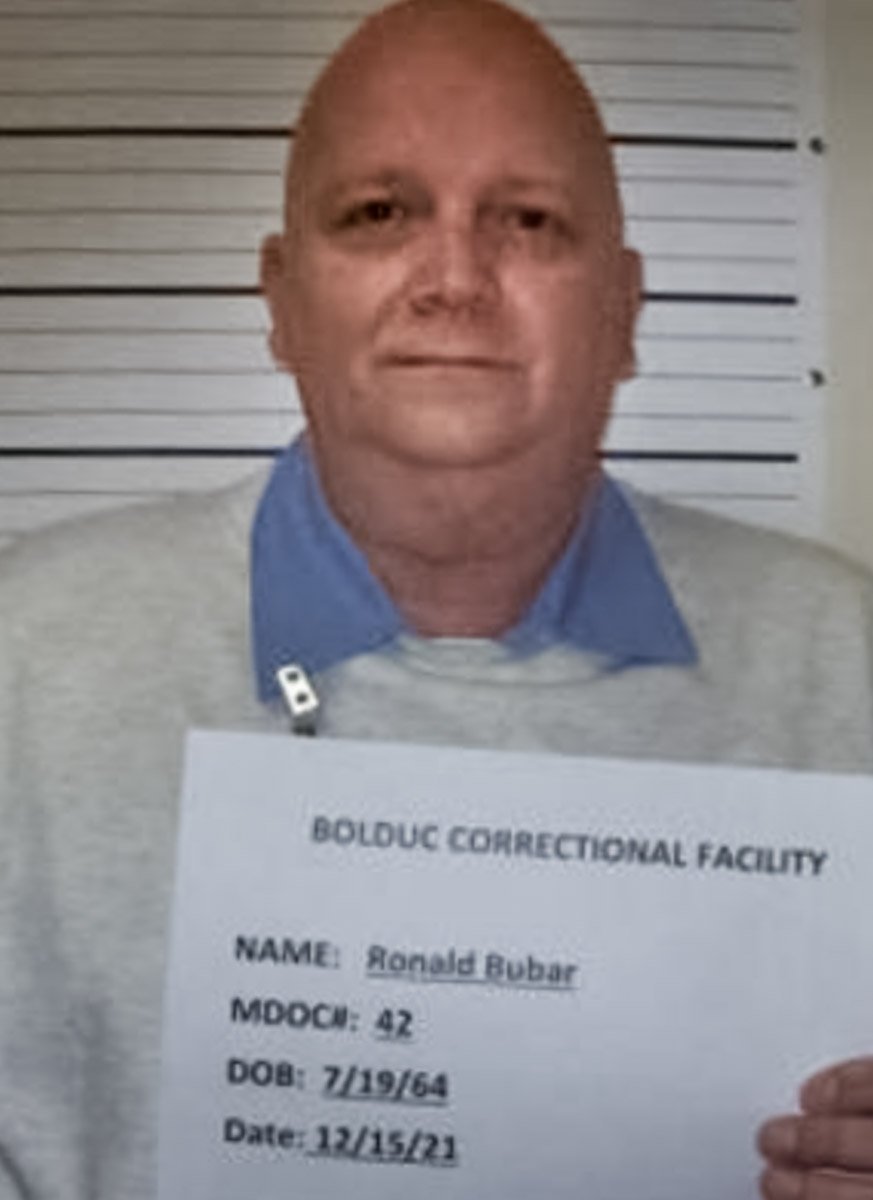

A model prisoner

Five years into his sentence, Ron’s life in prison was spotlighted by the Biddeford Journal Tribune. I can imagine that the reporter contacted the warden and asked them for a recommendation for a man that was doing well, and his name came up. Ron was thriving in prison. He was a leader of the Alcoholics Anonymous chapter, was an AIDS counselor for new prisoners, and president of the “Longtimers Club”—a position he campaigned for and was voted into by other prisoners.

Ron said, “What goes on in this institution is important to me. This is my town. I'm going to be here for the next 40 years. If you were going to be in a town for 40 years, wouldn't you get involved? You got people who do hard time and people who do easy time.”

Early on he divorced his wife and cut off visits from his son, saying, “it was a lot easier not to deal with some things.”

The article briefly mentioned the crime for which he was convicted, saying “she was found in the woods—nude, from the waist down,” and in the next breath, said, “Ron was a carpenter from Bangor with a wife and a child.” It seemed to cast Ron as a responsible, salt-of-the-earth, family man, especially in the context of the rest of the glowing piece on him, and it was infuriating. The author never even mentioned Becky by name. Ron’s earliest release date is February 13th, 2026.

Aftermath of Becky’s family

Meanwhile, Becky’s family’s struggles were only amplified.

Kristina: Looking back as an adult, I can see that it was a co-occurring issue—the depression and the substance-use. And then the depression from the substance use, and then using because you’re depressed, and it was just on and on. And I would say it... didn’t go away.

In years that followed her death, depression and alcoholism and darkness set in. Heather fell hard into substance abuse. There was lots of crying. It was a tipping point where the family took a turn for the worst. Becky’s name would come up and put everyone in a funk, listening to sad country music. Becky’s uncle, Kirk, and his wife, were involved in the “Parents of Murdered Children” group—Kristina remembered that her dad played piano for one of their events.

When Kristina grew up, she became a social worker and looked back at their family trauma, trying to understand and process it.

MMIW and MMIWG2S

Becky’s heritage is a rich part of Maine’s history.

Kristina: “We actually a part of two tribes, but you can only be recognized as one tribe in the state of Maine, so we are registered “Aroostook Band of Mi'kmaqs.” It’s actually called “Mi'kmaq Nation” now. But we’re also Maliseet, which are just two tribes that are up in northern Maine.

Becky was never identified in the newspapers as Native American—she was only referred to as ‘white.’ We only learned of her ethnicity through her family.

Native American and indigenous women, girls, and two-spirits are victims of murder, violence and rape at a much higher rate. And pioneers of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women movement are starting to get the recognition that they are due. In studies that have been conducted, it has been found that indigenous victims are less likely to get media coverage and their cases are often not investigated with the same rigor.

Kristina: “30% of indigenous homicides are covered in media, opposed to 51% of white homicides, and only 18% of indigenous female homicides are covered. 1 in 3 native women are victims of sexual assault, and 67% of those assaults are perpetrated by non-natives. Native women are murdered or sexually assaulted at a ten times higher rate.”

You can visit areyoupressworthy.com to see the bias in newsrooms when somebody goes missing.

We asked her if she believed the underlying causes of these disparities were relevant in Becky’s case.

Kristina: “She was beautiful—strikingly beautiful! She had beautiful dark hair and eyes... beautiful skin tone. Looked older for her age. Also I think he could see that she lacked supervision. So I think it was a recipe, something that some perpetrators can see. This kid is out roaming the roads, they’re more susceptible to being able to take a ride, whereas if a kid has good supervision and parenting, they would be less susceptible to be taken out for a booze cruise.”

A closing thought

At the end of the day, no matter how mature Becky looked and acted... no matter what the newspapers said or didn’t say, or what the police said, or what the public thought, Becky was just a kid—a 14-year-old girl who was adored by her friends and family—a girl who was just beginning her life, and who had it taken away by a predator.

Kristina believes in the inner strength of her cousin.

Kristina: “I like to think that she would have made it—would have made good choices—would have broken the cycle of poverty and substance use. I just feel strongly [about it]. She just had a presence about her. She was very maternal and a leader of the family, and I think she would have made it through.”

This is an MMIW case from Maine. Becky is part of the Aroostook Band of Mi'kmaqs, one of Maine’s Native tribes. By sharing her story, we are keeping her name alive and bringing awareness to the epidemic that is violence against Indigenous women and girls.

Learn more about the MMIW movement and how you can help.

Connect with Murder, She Told on instagram @MurderSheToldPodcast

Click here to support Murder, She Told

Grand jury indictment of Ronald Boobar for murder

Arrest warrant for Ronald Boobar

Ronald Boobar trial, defense exhibits

Ronald Boobar trial, prosecution exhibits

Ronald Boobar trial, prosecution exhibit, shoe prints from his Chevrolet station wagon

Ronald Boobar trial, prosecution exhibit, shoe prints from his Chevrolet station wagon

Ronald Boobar trial, prosecution exhibit, shoe prints from his Ron’s white sneakers

Ronald Boobar trial, prosecution exhibit, shoe prints from Becky’s neck

Letter for sentencing from Susie Glidden, Ron’s sister

Sources For This Episode

Newspaper articles

Various articles from Biddeford Journal Tribune, Sun-Journal, Kennebec Journal, Morning Sentinel, and primarily the Bangor Daily News, here.

Written by various authors including John Ripley, Nancy Garland, Ned Porter, Robert George, and primarily Margaret Warner.

Photos

Photos from Google Maps, various newspaper articles, and the Pelkey/Small family.

Interviews

Special thanks to Kristina Small.

Official documents

1988-11-10 - Autopsy report

1988-11-11 - Interrogation transcript, Ronald Boobar, Det. Zamboni, Det. Stewart

1988-12-05 - Grand jury indictment, Ronald Boobar

1988-12-05 - Arrest warrant, Ronald Boobar

1988-12-12 - Bail hearing transcript

1988-12-21 - Bail order

1989-01-11 - Motion for funds for private investigator

1989-07-03 - Jail grievance

1990-01-12 - Motion for funds for expert witness

1990-02-02 - Memo in opposition to motion to suppress

1990-02-16 - Memo in support of motion to suppress

1990-02-20 - Decision on motion to suppress

1990-03-13 - Memo in opposition to defense motion to exclude witnesses

1990-03-13 - Memo in support of defense motion to exclude witnesses

1990-06-14 - Memo in support of defense motion to exclude vehicle demonstration

1990, Nov - Dec - Various letters in support of Ronald Boobar for sentencing consideration

Defense Exhibits 1-5

Trial witness lists for both prosecution and defense

Exhibit lists for both prosecution and defense

Docket record for both Penobscot County and Somerset County

Email responses from both Bangor PD and Maine State PD regarding missing person record request

Credits

Vocal performance, audio editing, and research by Kristen Seavey

Written by, research, and photo editing by Byron Willis

Murder, She Told is created by Kristen Seavey