Anita Piteau: Huntington Beach Jane Doe

Anita Louise Piteau

Anita Louise Piteau was born in Augusta on March 9, 1942, the second child of George and Rena Piteau. Anita’s sister, Connie, was the eldest. Like many other fathers at that time, he fought in World War 2. But even after his service ended, George was largely absent, drinking and seeing other women. He didn’t disappear completely, though… he was around enough to have seven children with Rena.

Rena relied on the state to make ends meet. But despite their meager existence, Rena still managed to create a loving home. As a single mother of a large family, Rena expected the older girls, Connie and Anita, to help out. But Anita was still a kid, and not ready for so much responsibility. When Connie became a teenager, she was taken in by her paternal grandmother, and she was able to enjoy a better quality of life and focus on school.

This left Anita as the eldest of the six remaining children. Without Connie’s help and company, Anita had no one to share the responsibility with. Connie’s daughter, Laurie Quirion, later explained that “This also caused tension between my mother and Anita, because Anita wanted to be able to have nice things and not have to take care of everything.” Laurie thought that this resentment may have triggered some of Anita’s rebellious behavior.

In grade 7, Anita began skipping school, and both she and her mother were criminally charged. The Kennebec Journal reported that “an Augusta mother was found guilty […] of a charge of being responsible for the truancy of her 13-year-old daughter. She was fined $20.” Rena’s frustration and helplessness were evident in the courtroom: “Mrs. Piteau refused to testify but did say, as the judge was preparing to issue his verdict, ‘I didn’t know she wasn’t in school.’”

The judged ordered that Anita be “kept, disciplined, instructed, employed, and governed” at the state’s reform school in nearby Hallowell for 8 years—until her 21st birthday. Anita’s intake records from the school list only truancy as the cause for her commitment, but the fact that her family was so poor was doubtlessly part of the judge’s decision.

The Maine Industrial School for Girls

The Maine Industrial School for Girls had the appearance of a 19th century asylum. Neither a prison nor a mental institution, it was a little of both. Established in 1874, it was the oldest reform school in the state.

A few years after Anita left, a report on the school described the girl’s dorms as “depressing horrors,” and concluded that “the rooms of the girls are either stiflingly hot or bone-chillingly cold. All three dormitories should be torn down.” It listed many other sad features of the underfunded school, but worst of all, “the dormitories [did] not have the required number of toilet facilities for the number of girls” and, the “plumbing [was] always breaking down.”

This was Anita’s home for most of her teenage years.

The school was a public institution, and its students, “wards of the state.” Once a girl was placed there, in the words of the Board of Trustees, “fathers and mothers lost their parental rights and responsibilities.” This meant that parents could not remove their child—the school decided when and if they could be released.

Anita would have been housed with girls from all over the state. Some, like Anita, committed petty crimes, been truant, or even been caught smoking in public, but many other fellow “inmates” had learning disorders or special needs, were neurodivergent, experienced mental illness, or were pregnant or simply poor. The school was a catch-all for girls who didn’t fit into society, and whose parents were not wealthy enough to either care for them or pay for them to be committed to a private institution.

Many of the girls had histories of sexual abuse (although it was not necessarily why they were committed), and officials often overlooked the significance of these histories. In those days, sexual abuse was often thought to result from a girl’s character, and a girl who experienced abuse was often considered morally corrupt. Reports often described girls as “diseased,” “mentally defective,” and “low-grade.”

We went to Augusta to the Maine State Archives and reviewed most of the publicly available records. It was incredible to hold hundreds of original, irreplaceable documents under the watchful eyes of their staff. We were unable to get the entirety of Anita’s school records, which remain sealed until 2035, but with the support of the family, we were able to get a few of those confidential records.

34 other girls were committed the same year as Anita. She was one of four in for truancy. The majority of the girls were said to be “in danger of falling into habits of vice or immorality.” Only a few of the girls had actually committed crimes. The most popular reason for commitment in the previous year was “wanton and lascivious.” Although “incorrigible” was on the increase over the next few years, “danger of falling” remained a staple, as it had since the school first opened. All these words and phrases were thinly-veiled euphemisms that meant a girl was too promiscuous in 1960s officialese.

Reports about the staff varied. Some were kind, and others were not. Some were abusive, and a few years after Anita left the school, several were fired for their behavior. An official report claimed “the severity of punishments of the girls could not be tolerated.” Common punishments included cutting a girl’s hair or hitting her, locking her in the “dungeon”, and forcing her to kneel on the hard wood floor for a long length of time.

Despite being a girl’s school, some men worked there, and “one was having sexual relationships with some of the girls.”

During Anita’s stay, it seemed that life at the school was strictly scheduled, and girls were discouraged from talking while working. Leaving their rooms during leisure hours was a privilege. There was an emphasis on religion, and girls were encouraged to attend church and evening devotions. For someone as spirited as Anita, this atmosphere was stifling, maybe even depressing.

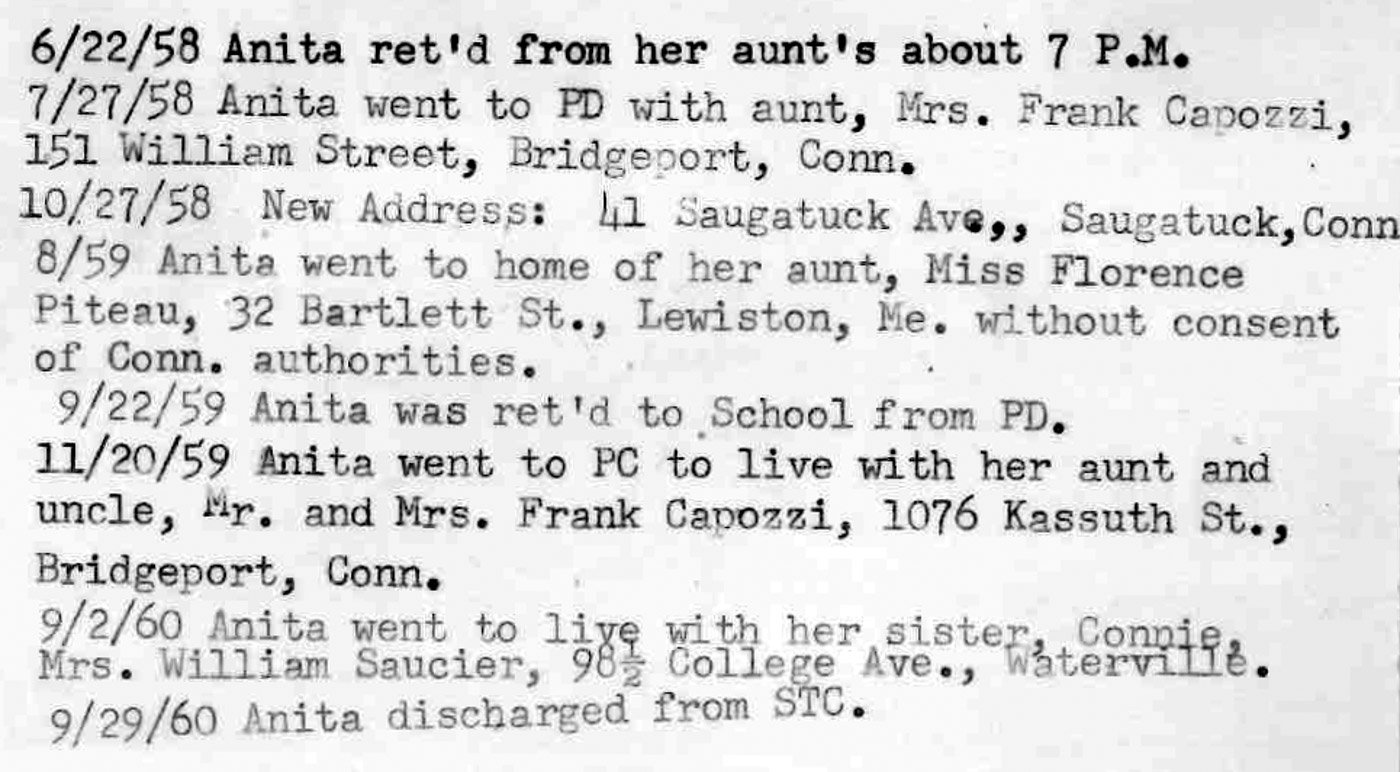

For three years there are few entries in Anita’s log other than her occasional home visits. On September 29th, 1960, after about three years at the school, Anita was finally discharged at the age of 18 years old.

When she was finally free for good, Anita was not reformed. Laurie explained that “she came out even more determined to get what she wanted and live on her own terms without anyone telling her what to do.”

Road Trip to Los Angeles

When she left the reform school, Anita lived with her mother in Augusta and worked, but didn’t hold down any particular job for too long. Laurie later explained in her book, “She jumped from job to job staying long enough to learn it and get a couple paycheck, and then [she] mov[ed] onto the next thing.”

Going out together dancing and drinking was how Monique met her husband, Archie, and, according to Laurie, “The three of them spent a lot of time together going out dancing and drinking.”

Saturday night dances were held at community centers, dance halls, and barns, and there was always live music. Laurie explained that “Anita knew many people from her time going out.” This was how she met the guys she went to California with. “They asked her if she wanted to go with them” and “She said ‘Yes,’ knowing [it] was likely her only chance to get there (because she couldn’t afford to go on her own).”

One day in early December 1967, the guys pulled up to the apartment house she shared with her mother. There wasn’t much room for luggage, but she didn’t have much anyway. Rena hugged her daughter and told her to make sure to write.

California Dreaming

In January, Monique had exciting news to share: she had received a postcard from Anita in California. In the postcard, dated January 9th, Anita wrote that she’d been in California for 2 weeks, and promised to write more soon. In February, Anita wrote a letter to her mother with more details about her travels.

When Anita first arrived in LA, she met a woman who helped her get a job and offered her a place to stay. The guys wanted to return to Maine, but Anita wanted to live and work there for a while. She assured them she would be able to get back on her own once she made a little money.

The woman Anita lived with had two teenage sons and lived in Whittier, a rapidly-expanding bedroom community just outside Los Angeles. Anita’s new home was on Sunshine Avenue, aptly-named, a street lined with single-story homes and palm trees in the working-class neighborhood.

When she wasn’t working, Anita traveled around the state, often with the woman she lived with. In her letter to her mother, she wrote that they had visited tourist attractions in LA, like the homes of movie stars, and planned to go to San Francisco. They’d taken color photographs together that Anita promised to send to Rena once they were developed.

She also dated. Her relationships seemed to follow the same pattern as her jobs—nothing really stuck. She wrote that she “wasn’t going out with anybody,” but she had previously dated a Mexican truck driver, and had just met a “very nice” nightclub singer.

Anita enjoyed the local nightlife, and wrote to her mother, “they sure have some nice places to go out and dance.”

Anita wrote that she would return to the East Coast “in about May” — first to her aunt Brigitte’s in Connecticut, then to her mother Rena’s in Maine. Although she was having a good time, she wanted to come home eventually.

Anita Piteau’s last letter

The month of May came and went without word from Anita. Her mother had never received the second letter with color photographs she had been promised. No one else had received a postcard or a phone call. The letters they had sent to the Sunshine Avenue address had gone unanswered. Without a phone number, they had no way of getting in touch with her except through the mail. They did not know the name of her roommate, and they didn’t know if Anita still lived with her.

In June, the family became increasingly worried. Laurie remembered there were a lot of phone calls as her parents and the other adults tried to figure out what to do. Anita’s sister, Monique, had her husband, Archie, call the Whittier Police, who eventually dropped by the Sunshine Avenue home to check on Anita. The home was empty. Seeing nothing wrong but free spirit who had come to California and joined a growing subculture, the Whittier PD did not consider Anita a missing person and wouldn’t take the report.

To Anita’s family, it didn’t add up. Though she was a free spirit, she loved her family and would have informed them if her plans had changed.

Anita seemed to have vanished, and time moved on without her.

Huntington Beach Jane Doe, 1968

Laurie started using the internet as soon as it became available, and by the early 2000’s started looking through missing persons databases, searching for any mention of Anita.

By the 2010s, the internet had grown. Laurie’s daughter, Dakota, took on the task of searching through Jane Doe listings online. One night, she called Laurie over to the computer and showed her a photo...

The woman had dark hair and a round face. She was in her 20’s or 30’s, and the description next to the sketch included blood type, height, and weight. She had pierced ears, brown eyes, brown hair, and was described as “white and/or Hispanic.” Her teeth were in poor condition, but she had otherwise been healthy. Jane Doe had been found on March 14, 1968—a month after Anita’s last letter. The sketch was a recent one, but the site also included older sketches that had been made back in 1968 and postmortem photographs. When Laurie and Dakota took it all in, they felt there was a good chance that this Jane Doe was Anita.

This was the first promising lead they’d had in years, but the site did not tell them which law enforcement agency to contact. Not sure where to turn, they called the Whittier police, who told them they didn’t have the resources to help and suggested a private investigator—something the family couldn’t even afford.

In 2016, Laurie’s mother, Connie, died. At this point, her grandmother, Rena (Anita’s mother), had passed, too. This was a crisis point for Laurie. At this point, she thought that none of Anita’s siblings would ever find out what happened to their sister.

What Laurie didn’t know, was that another search was underway—one that would finally solve the mystery that had plagued her family all these years. Just around the corner was the answer they were looking for: what happened to Anita after the last letter—the one Anita wrote in February 1968.

Just 17 miles south of Anita’s last known address in Whittier, a terrible discovery was made. The Huntington Beach Police Department found a body—a body they would spend 50 years trying to identify—the body of Anita Piteau.

Click here for Part 2.

This text has been adapted from the Murder, She Told podcast episode, Anita Piteau: Huntington Beach Jane Doe, Part 1. To hear Anita’s full story, find Murder, She Told on your favorite podcast platform.

Click here to support Murder, She Told.

Connect with Murder, She Told on:

Instagram: @murdershetoldpodcast

Facebook: /mstpodcast

TikTok: @murdershetold

Anita Piteau, as a teenager, at the Maine Industrial School for Girls, Hallowell, ME (Maine State Archives for Murder, She Told)

Main classroom building, Maine Industrial School for Girls, Hallowell, ME (Maine State Archives for Murder, She Told)

Map of the Maine Industrial School for Girls campus (Maine State Archives for Murder, She Told)

Anita lived at Flagg-Dummer Hall, Maine Industrial School for Girls (Maine State Archives)

Interior corridors at the Maine State Industrial School for Girls (Maine State Archives for Murder, She Told)

Anita Piteau’s comings and goings at Maine Industrial School for Girls (PC: Maine State Archives for Murder, She Told)

Anita Piteau at her older sister, Connie’s, wedding

Anita Piteau sitting at the table, her mother, Rena, pouring coffee

Anita Piteau (From Laurie Quirion)

Anita Piteau (Huntington Beach PD)

Anita Piteau’s final letter (Laurie Quirion)

Sources For This Episode

Newspaper articles

Various articles from Chula Vista Star-News, Kennebec Journal, Kitsap Sun, Los Angeles Times, Morning Sentinel, New York Post, Newsday, Orange County Register, Press-Telegram, Santa Maria Times, Sun-Journal, TCA Regional News, Telegraph Herald, The Daily Review & Sunday Review, and the Lompoc Record, here.

Written by various authors including Alejandra Molina, Andrew Galvin, Andrew Binion, Anthony DeStefano, Bill Hazlett, Colleen Shalby, David Li, Eric Russell, Frank Anderson, George Laine, Hannah Fry, Keith Sharon, Leila Miller, Michael Levenson, Nate Jackson, Nick Sambides, Nicole Santa Cruz, Robert Gettemy, Scott Schwebke, Selene San Felice, Steve Emmons, and Wendy Post.

Online written sources

'457UFCA - Unidentified Female' (TheDoeNetwork), 5/9/2010

'Calif. Police "Desperate to Identify" Murder Victim in 1968 Cold Case' (CBS News), 1/28/2011, by Naimah Jabali-Nash

'68-00745-C - John/Jane Doe Summary Form' (Orange County Sheriff's Department), 10/1/2016

'Anita Louise Piteau' (Find a Grave), 7/23/2020, by John P. Bell

'Family gets 'sense of peace' after DNA identifies Maine woman as 1968 homicide victim' (Bangor Daily News), 7/23/2020, by Nick Sambides

'Southern California Police Solve 52-Year Murder Mystery, Identify Victim at Last' (Courthouse News Service), 7/23/2020, by Martin Macias

'Investigative genetic genealogy helps Huntington Beach Police, District Attorney’s Office identify Maine woman as 1968 homicide victim and finds her killer' (Orange County, Office of District Attorney), 7/23/2020

'Maine family grateful after 52-year-old cold case murder solved' (WGME CBS 13), 7/24/2020

'Anita Piteau' (Fandom), 5/4/2022

'Hallowell library to host program on Stevens School May 5' (CentralMaine.com), 4/29/2023

'(Huntington Beach PD announcement)' (Facebook), 7/23/2020, by Huntington Beach Police Department

Books

The Last Letter by Laurie Quirion, written by Dakota and Marisa Allen

Interviews

Special thanks to Laurie Quirion for sharing her memories and agreeing to be interviewed.

Official records

Special thanks to the Maine State Archives for allowing us to view all of the publicly available Stevens School Records (aka Maine Industrial School for Girls). They also made an exception at the request of the family and provided certain documents from Anita’s student file.

Photos

Laurie Quirion and Anita’s family, the Maine State Archives for Murder, She Told, Huntington Beach PD

Credits

Vocal performance, research, and audio editing by Kristen Seavey

Research, photo editing, and additional writing by Byron Willis

Writing by Anne Young

Additional research by Sarah Lafortune and Samantha Coltart

Murder, She Told is created by Kristen Seavey.