Bring Her Home: Virginia Pictou Noyes

Virginia Sue Pictou Noyes, Parts One and Two

It was the middle of the night in October of 1990 in potato country in rural Maine—2 miles south of Fort Fairfield, the nearest town—and a fire was building. Smoke was pouring out every crevice in the modest mobile home. A large family was in peril, and they had no idea.

Earlier that Friday night—at about 10:00PM—Virginia, a young mother of five, had kicked out her husband after an alcohol-fueled spat. The five children, ranging in age from just months old to 8 years old, had all retired for the evening, and so had she.

Sometime in the wee hours of the morning, the oldest son—Randy—awakened to the smell of smoke. He ran to his mother. But by the time she realized what was happening, the fire was unstoppable.

She worked quickly to get the children to safety. Her youngest baby girl was sleeping with her. Randy was old enough to manage on his own, and so was the next oldest boy, who was 6.

Once the four of them made it to safety, Virginia tried to rescue her two remaining children, who were 1 and 2 years old. The 1-year-old boy was colicky and was separated in his own bedroom. Virginia started down the corridor to his room, but soon retreated because of the heavy smoke and the heat of the flames. She emerged from the trailer, her lungs burning, coughing violently. She tried to reach his bedroom from the exterior of the trailer home.

Virginia ripped off the clear plastic sheeting that was placed over the windows, and broke out the glass, but as soon as she made a new opening in the trailer, it opened up a draft to fuel the fire, and within seconds, the entire trailer was engulfed in flames.

As she stood there, helpless and stunned, her childhood home burned before her eyes with two of her youngest children.

The fire department, sifting through the rubble, tried to identify the source of the blaze. Though it was unconscionable to think that someone would have tried to kill 5 children and their mother, they had to do their diligence. Their preliminary inspection focused on oil-burning forced-air furnace. On Monday, the Maine Fuel Board, a regulations agency, sent an investigator to take a closer look. He concluded that the fire started from a leak in the fuel pump that ferried home heating oil from the storage tank to the burner.

Virginia’s family wasn’t so sure.

Her husband, Larry Noyes, and his brother, Roger, had a long criminal history that included arson, and they thought he might be responsible. Virginia’s brother, Robert, told us, bluntly: “We think that Larry came back and set the house on fire.”

Growing up in Fort Fairfield, ME

Virginia and Larry had grown up together in Fort Fairfield. They were nearly the same age—Virginia was just one month older. Larry was white, and Virginia was Native American. Virginia was dirt poor and part of a large family. Her parents, Robert Pictou Sr. and Susanna Pictou, were both from Nova Scotia, Canada, and were full-blooded Mi’gmaw. Though the words Mi’kmaq and Mi’gmaw are used interchangeably, the Pictou family uses the term Mi’gmaw to describe themselves, and we will follow their lead.

Virginia’s father, Robert Sr., had three children from a prior marriage and her mother, Susanna, had three children from a prior marriage. And they had four children together—a total of 10 kids—of which, 7 of them lived in Fort Fairfield with their parents, including the second-youngest, fiery Virginia Pictou.

We spoke to her older brother, Robert. He was the first born of the four children from the union of Robert Sr. and Susanna and was four years older than Virginia.

Robert: “Virginia and I were opposite and alikes at the same time. We were always vying for attention at the house. Oil and vinegar at times but we were also water and water, too.”

Virginia Sue Pictou was born in Fort Fairfield Hospital on April 2nd, 1967, and she was soon brought home to their rudimentary rural home, which the family referred to as “The Old House.”

Their home was primitive. They were grateful to have electricity, but they had no running water. A 55-gallon drum outside held kerosene, and as a daily chore, the kids would fill a 2-gallon pail to refill their heating stove for the day. It was a cold climate—the average temperature in January was just twelve degrees. Kids were 2 and 3 to a room, and there was a large cast-iron sink in the kitchen where the children would bathe.

Virginia’s father, Robert Sr., worked as farm hand, primarily on the potato fields. In the summers, when the children were out of school, the whole family would travel to work the blueberry fields, using tined rakes to harvest the small flavorful berries.

The kids grew up speaking their native tongue at home, but would travel each day by bus to public schools in Fort Fairfield where only English was spoken.

Robert: “At home, Mi’gmaw was the primary language used at home. My mom was a fluent speaker. My dad later became a fluent speaker. Initially he was a fluent speaker until he went to residential school. When he graduated he said he couldn’t speak Mi’gmaw any more until he met my mom. And then—through the language of love—he taught her English and she taught him Mi’gmaw. But at home, it was always Mi’gmaw. That was the first language I grew up with—all of us grew up with.”

It was a rough and tumble childhood. Virginia’s mom, Susanna—when she needed some space and peace for herself in the kitchen—would kick all of the children outside to play. The kids had free reign in the sprawling fields and forests of the countryside. In the winter, Robert remembered sledding down the miles of gentle slopes, and building forts in the snow. There was a “farmer’s dump” on the edge of some woods near their home, and they would often go diving for treasure, finding adventure amidst the scraps. One time, the gaggle of children all managed to stuff themselves inside an old washing machine and rode it down a snowy hill, nearly breaking an arm in the process.

With so many children, and so little to do—especially in the frigid winters—sometimes Susanna would have to get everyone to focus on an activity to have some peace in the chaos. That’s how they all learned to bead.

Robert: “My mom was a prolific beader. I can almost pat myself on the back and say I’m pretty good, but I’m a shadow of the master that my mom was. My mom was a powerhouse to deal with. She would let you know where you stood—all 4FT 8IN of her. So she would declare a ‘Craft Day,’ and she would break out her beads. Everyone would have to sit at the kitchen table. It was amazing that when that happened, things quieted down. And my mom would say, ‘You can’t do art and argue at the same time.’ So I think that was her way of babysitting us, or dealing with the craziness with those cold winters in northern Maine.”

Money was tight, and the wages that Robert Sr earned as an agricultural laborer couldn’t support the large family alone. They relied on food stamps, school lunches, and commodity foods which was a government food program that doled out rations in no-frills packaging with labels like “cheese,” “pork,” and “powdered eggs.” And of course, potatoes—the primary crop in their region.

Drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes were both common in the Pictou family. Susanna drank regularly to excess. Robert Sr. barely drank at all—just having a small amount socially here and there. The kids were all drinking and smoking cigarettes by their teenage years. Violence in the Pictou home was also not uncommon.

Virginia got pregnant and dropped out of school when she was just 14. She met a boy, 3 years her senior, at the Roller Rink in Caribou. His name was Ward. She gave birth to her first son, Randy Pictou, in 1982. Two years later, at 17, she gave birth to Christopher Pictou.

Virginia loved cars, and loved working on cars. She was upbeat. She was happy. She was popular. Her older brother, Francis, said of her, “Virginia was a lot of fun. She kept me on my toes.” She did well in school, earning straight A’s. Her oldest sister, Agnes, remembered her as an attractive young woman who wanted to maintain her appearance. She recalled Virginia getting back into shape as soon as possible after her babies were born. She said, “She was bright, and witty, and resourceful. She could make a good meal out of whatever she had, like our mother.”

1985 - The Noyes boys

Larry was a neighborhood boy, and so was his older brother, Roger Noyes, who was two years his senior. They had both taken a fancy to Virginia, and they were both known troublemakers.

Robert: “He enjoyed inflicting pain on anyone around him. He really enjoyed it. In 2nd grade he broke Larry’s arms, and as that was healing, he broke his other arm. He was really good at breaking arms—he would twist them until they snapped. And he also did that to his sisters. Both of them were abusers. Unfortunately my sister was a loser-magnet. She could pick the loser in a crowd, the worst person in a crowd, she could pick ‘em.”

1987 - Virginia’s mother dies

Virginia’s mother, Susanna Pictou, died after a short battle with lung cancer at Presque Isle Hospital. She died on March 14th, 1987, at 55 years old. Virginia was just 19. Dorsey Funeral Home in Fort Fairfield handled the services; they crated up Susanna’s body and shipped her to Nova Scotia to be buried. Robert recalled that his dad really struggled with his mother’s death, and he moved back to Canada, his birthplace, never to return to Maine again.

Around this same time, Virginia’s siblings moved away from Fort Fairfield and gave her the Pictou home to raise her children. It was a turning point in the lives of the family. The seven siblings who had all grown up in Fort Fairfield had scattered, with the exception of Virginia and her two young sons.

Larry and Roger got out of prison and they all started seeing one another again.

1987 - Virginia and Larry’s incident with cops

It was the evening of Saturday, August 15th, 1987, and Fort Fairfield police got a call that two vehicles were racing on Forest Avenue, the same road that Virginia was then living in the family home.

As Officer Gray approached Forest Avenue on a gravel side road, she encountered Virginia’s 1971 Oldsmobile Cutlass going the opposite way. She blocked their path, got out of her cruiser, and approached the driver’s side window. Larry was driving, but it was Virginia’s car. He was slurring his speech, and he reeked of alcohol. She told him that he was under arrest for driving under the influence and that he would be tested back at the station. That left Virginia in the front passenger seat and two friends in the back. While the cop was occupied with Larry, Virginia slipped into the driver’s seat and took off, spinning the car around and sending a shower of rocks into the windshield of the cruiser, putting a crack in it.

Officer Gray had a choice: to go after Virginia or to stay with Larry. She went after Virginia.

Larry took off on foot into the potato fields.

Virginia was racing through farm field roads at 50-60 miles per hour and Officer Gray was in hot pursuit. But after a couple of miles, she was able to lose her in a cloud of dust.

Meanwhile, Officer Gray called in backup from the state police. A state trooper and a sheriff’s deputy showed up with a scent dog named Chico and started tracking Larry. As they went along, they found clothes that Larry had stripped off, trying to fool the canine, but Chico continued to track the scent. Eventually the dog found Larry, naked and alone in the woods, and bit him. They took him to Community General Hospital in Fort Fairfield, where he was treated for a dog bite and abrasions, and then booked him at Aroostook County Jail, charging him with a DUI and an offense called “escape.”

After Virginia submitted to the arrest, she was charged with failure to stop for a police officer, allowing her vehicle to be operated by a drunk driver, and the most serious charge, driving to endanger, a Class E misdemeanor. When she failed to meet bail, she was booked at Aroostook County Jail.

She may not have realized it, but when this debacle occurred, she was pregnant with a little girl.

Robert hadn’t realized how close Virginia and the Noyes brothers had become.

Robert: “I was never friends with them. I never got a good vibe off the Noyes brothers. I never knew that Virginia was dating Larry until I was long out of the picture because if I had anything to say about it, I would have fought her. Not physically, but argue with her, like ‘This person is not a good person to be with.’”

1988-1992 - More kids, relationship with Larry deepens

On April 5th, 1988, Virginia gave birth to her third child, Ashley Sue Noyes, at Presque Isle Hospital. Four months later, she was pregnant again, but Larry was not the father. In May of 1989, she gave birth to Jesse James Pictou in Presque Isle, and he had signs of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome.

Robert: “When it comes to what is normal drinking, I didn’t know what it was... And I think that led to a lot of difficulties for us as a family when alcohol was involved. Because it wasn’t just alcohol, it would be marijuana and pills and stuff like that. It was just a vicious cycle that unfortunately once you’re in the middle of this whirlwind you don’t know how to get out. And I think Virginia was stuck in that. She still took care of her children and tried to be responsible, but I think in my heart of hearts that she had a substance abuse problem.”

On August 12th, 1989, Larry and Virginia (who were both 22 years old) decided to get married, and Virginia officially became Virginia Noyes. In short order, Virginia was pregnant again, and on June 10th, 1990, gave birth to Brittany, her fifth child.

It was then, in October of 1990, after about a year of marriage, that the Pictou family home burned to the ground, and two of Virginia’s children—Ashley Sue and Jesse James—perished in the fire.

Larry and Virginia found another home. In May of 1991, at 24 years old, Virginia gave birth to her sixth child, Myley, and a year later, in July of 1992, gave birth to her 7th and final child, Lanae.

1993 - Virginia’s disappearance

It was early spring in 1993, and Larry, Roger, and Virginia were 2.5 hours from home, in Bangor, to visit her father-in-law, Roger Noyes Sr, who lived there. It was a Saturday night, April 24th, and they were out at a bar on State Street called Judy’s. Just before 10:00PM, Virginia had had enough, grabbed the keys and went to walk out the front door. Just before she reached the saloon-style swinging doors, her husband, Larry, kicked her from behind, sending her smashing through the doors and onto the pavement. He climbed on top of her and began beating her face, and then his brother Roger joined in. The bartender yelled that they had called the police, so the Noyes brothers dragged Virginia around back where they continued the assault. Police arrived and found Virginia visibly shaken and sobbing uncontrollably. She initially told officers that both Larry and Roger were involved because, quote, “they were drunk,” but when Larry approached her, she said it was Roger alone who had struck her. In their arrest report, officers indicated that Virginia seemed afraid of her husband, and they wrote her up an emergency order of protection that night.

They took her to Eastern Maine Medical Center to be treated for her injuries. Virginia repeatedly told police that she had to get back home to her children.

They charged Larry with domestic assault and took him to Penobscot County Jail. As he was being driven away from the bar, he kicked at the windows of the cruiser and screamed at his wife. He was booked, but bailed out very shortly by his either his brother or his father. Roger, who police described as drunk and staggering, was charged with assault and given a court summons but released on his own recognizance.

After posting bail, Larry returned to Pat’s Place looking for Virginia, but he couldn’t find her. Somehow he ended up with the car that they had driven down the previous day. He said he left the bar alone and started heading home around 4:30AM, checking at every rest stop along the way, suspecting that she may have hitched a ride. He said he arrived home around 6:30AM back in Easton, a town near Fort Fairfield. They had a babysitter for the evening, and Larry said that the babysitter told him that Virginia had called the house two hours prior—around 4:30AM—from Houlton, looking for a ride. Larry said he stayed home with the children all day that Sunday, waiting for Virginia’s arrival. In another account, the telephone call she allegedly made from Houlton was made to an uncle of her husband’s but Robert found that difficult to believe.

Robert: “She would’ve called Agnes! Francis, at that time, I believe was in northern Maine. We all went to Agnes when there was crisis. No matter what happened. Agnes told me a number of times that Virginia would show up all beat up and bruised. She would say, ‘I just need a place to stay for a couple of days while things cool down.’

Hospital records from that evening indicated that Virginia left on her own accord sometime after 1:00AM after they had triaged her and taken photos of her injuries. The staff’s attention was drawn to a shooting victim that came in that night, and Virginia left without checking out with anyone.

In an article in the Bangor Daily News, Maine State Police said that they were “reasonably sure” that she was seen around 4:30AM at an Irving Big Stop in Houlton, 120 miles from Bangor and on her route home, but Robert believes that information is based only on Larry’s account of the evening. In Robert’s mind, the last reliable sighting of Virginia was at the hospital, and anything after that was speculation.

Within a couple of days, Larry reported Virginia missing to the police. Bangor PD was leading the investigation in the early days, but eventually the Maine State Police took it over.

The charges against Larry and Roger from the night of Virginia’s disappearance were dropped by the district attorney because the key witness had vanished.

On the Monday after her disappearance, two of Virginia’s siblings—Agnes and David—drove up and down I-95 to measure the time it might take to ride or walk from Bangor to Houlton. They then did the same thing from Houlton to her home. They were trying to test Larry’s story out to see if it was even possible. Robert, who was 30 years old at the time, helped to handle many of the responsibilities that arose.

Virginia’s dad, Robert Pictou Sr., later told the Bangor Daily News that Larry had approached him in a potato field they were both working, confessed his love for his daughter, and denied all the rumors that he had anything to do with her disappearance. Robert Sr. told him, “You did it, too, didn’t you?” Larry walked away from the conversation. Robert Sr. told the press, “I know he did it... And all my sons and daughters know it. My native people know it. And all the people in Fort Fairfield know it.”

Larry said that he believed she was still alive and that her family was hiding her. He also said that Virginia left a note that read, “I am leaving in April or August 1993, and I’ll be back when all my children turn 18.” But in the same breath he also said that she might have been having an affair with his brother Roger, and that he might know what happened. He explained that she and Roger had dated before they were married. He said the night of her disappearance, he got angry with them when his brother familiarly slapper her butt, but denied that he even hit Virginia at all that evening. After her disappearance, Roger admitted to him and their mother that he had loved Virginia and said that she was the only love he’d ever had. Their sister, Terry, confirmed the close relationship between Roger and Virginia. Larry said, “The whole family thinks Roger might be involved.”

No one in the Pictou family believed that Virginia would abandon her children. She loved them. Even one of Larry and Roger’s employers, Barbara Bird, said, “[Even though she was worn out from childbearing], she never would have left them. No matter what the circumstances, she didn’t want anyone else to take care of them. If she were alive today, she would be with her children.”

1994 - September

In September of ’94, a year and a half after Virginia’s disappearance, Robert Sr. was convinced of his daughter’s demise, and said that her spirit, “Red Bear,” was restless and could not find peace until her remains were found and buried with her family. He said, “I know in my heart she is no longer with us in this world.” According to the journalist for the newspaper, Gloria Flannery, police agreed with his assessment.

Robert Sr. had traveled from his home in Sydney, Nova Scotia—one of the easternmost parts of Canada—to a native fortune teller, over 2,000 miles away, in the province of Ontario. He next was pursuing a ceremony in a sweat lodge and a shaking tent ceremony, which is often conducted by a spiritual tribal leader often referred to as a shaman.

Virginia was constantly on his mind. He got an image of her laminated.

Robert: “and he had one of my mom... And he used them, in essence, like placemats. When he was eating, he’d always have one hand with them, so he was always eating with them.”

1997 - Lead detective’s opinion on the case

In 1997, the lead detective from the Maine State Police retired, and although the family wouldn’t know it at the time, he later gave an interview to the Bangor Daily News. He said, “In my opinion, Virginia disappeared at the hands of Larry. If I’d had the evidence to arrest Larry, I would have. Everything pointed toward him.” He recalled that Larry underwent a polygraph examination and the results indicated deception. But he said that they followed up all the leads that they could and said they were at a dead end.

2015-2018 - Larry’s decline and death

In 2015, Larry was 48 years old and in poor health. Bangor Daily News later did a spotlight on his girlfriend, Carolyn Fish. She said that from the moment that they started dating, they were inseparable—in part because Larry required hourly care for the health problems that had been caused by his lifelong drinking. They were in and out of shelters, campsites, and apartments together.

In early 2017, during winter, Larry was hospitalized for 170 days after he suffered an alcohol-induced stroke. He was diagnosed with advanced liver cirrhosis, but still he continued to drink. In late 2017, Larry became violently ill and required a 10-day hospital stay for pneumonia and sepsis from an infected leg wound. In December, they had a short stay at the Bangor Area Homeless Shelter, but within a week were asked to leave because they struggled abiding by the rules. Over the next couple of months, they spent the last bit of money on motels and alcohol, and in February, returned to the shelter. By this point, Larry’s eyes had turned a sickly yellow from drinking, and they would stay for 4 months until they were able to get an apartment. Larry’s health seemed to be on the upswing. On June 1st, 2018, they moved into an affordable housing unit on Court Street, but as old friends started dropping by, Larry relapsed. Within the first months, they had violated their lease 4 times due to loud parties and unsanitary living conditions. July 25th, 2018, Larry died at the hospital at 51 years old.

He died without revealing any further information about Virginia’s disappearance.

At this point, Larry, Roger, his mom, Jane, and his father, Roger Sr., were all gone.

2017 - Explosive revelation

Before Larry died, his nephew (Roger’s son), Ryan Noyes, made an explosive revelation to the organizer of the Facebook page for Virginia, Jaime Owens. He gave her the names of three people who were involved with the killing, including his own father, Roger. Ryan said that a car that was used in the killing was burned inside a barn in Easton and that it was possible Virginia was inside. Jaime had heard that he told someone in the community some details about the killing, so she decided to ask him what he knew. She provided the transcript of the Facebook messages to CBC News, a Canadian journalism outlet, and they revealed that Ryan said, “I don’t think there is anything left to be found”—presumably, of her remains. They contacted Ryan for an interview, but he declined, saying, “I don’t want to talk about it. This is 20-something years old... [and] I had no part of it.”

Virginia’s older brother, Francis Pictou, contacted the Maine Attorney General’s office—the prosecutors that would make charging decisions and could direct investigative focus. When he asked them about Ryan’s statement, an official told him that Ryan had told Maine State Police the same information directly a couple of years prior, and police had conducted a search of the location. They also said that they planned to interview remaining members of the Noyes family about the case.

This unfolded just days before the Pictou family was scheduled to testify at a hearing that was being conducted by the Canadian government looking into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG).

2017, Oct - Canadian National Inquiry Hearing

Robert traveled from the other side of Canada to join his family to testify in Sydney, Nova Scotia, at the Membertou Reservation. They were one of 50 families and survivors that agreed to participate from Membertou, and one of ten that gave public testimony. The national inquiry was initiated by the Canadian Government in August of 2016, and concluded about three years later in June 2019.

Residential schools

It’s unclear exactly why, but there is a huge disparity between the frequency at which Native women go missing or are murdered compared with white women. It may be a combination of factors—in Virginia’s case, it may have something to do with the poisonous residential school system in Canada that her father was subject to. He is a survivor. So was her mother.

Robert: “So here’s my dad at the age of 6 who gets taken away from everything that he knew, placed with other people, and there are people in positions of authority telling him things to do in a language he did not understand, and I’m punished because I don’t do those things, immediately, as a child, at the age of 6. Children are resilient. And what ended up happening, he was able to identify the words in 172 as his name. So when he heard those syllables put together, he realized that they were talking to him, and telling him what to do.

Robert: “He could stand on the top of his building, and he could see his house, but he couldn’t go there for 7 years. When he graduated, he said he couldn’t tell time. He spoke English, but he couldn’t write or read.”

The residential school program in Canada was designed to, over generations, assimilate the many different native tribes into dominant Canadian culture by isolating children from their families.

Over the course of the system’s roughly 120-year existence, an estimated 150,000 children went through the program. At its height, 1 out of 3 native children were under compulsory residential school enrollment. The kids would be sent to often far-flung locations, where they would live full-time at a school administered by a Christian church.

Children were punished for speaking the native tongue and were forced to use English. Physical and sexual abuse was rampant. The harsh discipline administered would not have been tolerated at any other Canadian school. They were forced to work long hours—some were likened to concentration camps. A historian, John Milloy, argued that the system’s aim was to, quote, “kill the Indian in the child.”

Families would frequently travel to the schools and sometimes camp outside to be close to their kids. One of the leaders of the program noticed this trend and argued that the schools should be strategically located further away from reservations to make the journey more difficult for families, discouraging them from visiting. He also encouraged schools to require students to stay on campus during holidays and breaks because he believed the trips to see their family would disrupt their assimilation. When families did have visits with their children, they would often be supervised, and the school official would often only allow English to be spoken—effectively making communication impossible.

Children suffered from malnourishment, starvation, and disease, and many died. Though estimates vary widely, as little as 2% but as many as 20% of all children enrolled perished. Huge fields of unmarked graves containing hundreds of bodes have been uncovered in the past 10 years.

When they ‘graduated’ from these institutions, they would often face new difficulties returning to their families. They could no longer speak their native tongue. They were unfamiliar with their own culture. They felt like outsiders in their own home.

In the late 2000s, Canadian politicians and religious organizations began to recognize and apologize for their roles in the system. In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada determined that the residential schools were a system of “cultural genocide.” The system ultimately proved successful, though, in disrupting the transmission of Indigenous practices and beliefs across generations.

In learning about residential schools, it seemed like something that would have existed in the 1800’s, but I was stunned to learn that the height of student enrollment happened in the 1960’s, and the final residential school didn’t close until 1997. Even today, at 84 years old, Robert Sr. still grapples with lingering trauma from his experience.

Robert: “His biggest fear right now is actually going to sleep. He’s 84 years old, and he says when he sleeps he becomes that little boy again, and he wakes up drenched in sweat.”

Robert: “’Cause it isn’t a simple one of someone going missing... It’s residential school, it’s MMIW, it’s domestic violence, it’s substance abuse, it’s being raised around substance abuse... There’s all kinds of factors in this. Unfortunately, Virginia was just that perfect candidate. It was gonna happen, it was just a matter of when unfortunately.”

Criticism of the police / the system

Whenever he has tried to follow up on Virginia’s missing person case with Maine authorities, he just gets the runaround.

Robert: “As familes, we keep bumping our head in the bureaucracy. We don’t know who we need to talk to or what we need to do. We just know that Virginia’s missing, and we’re just trying to find some kind of justice. I believe that her two assailants have passed, and we just want to bring her home. One of the things we’ve run into over and over and over again is being passed around. ‘That’s not my job. Oh, you have to talk to this department. You need to talk to this person.’ We just want to know what’s going on, what can we do to help? You need to make it easier for the victim’s family. They’re dealing with enough grief already with a missing person, and then you hit up with ‘You’re talking to the wrong person,’ or ‘We can’t tell you that, it’s an active case.’”

We asked Robert what he thought happened to Virginia

Robert: “They... killed her. It may have been accidental. It may have been accumulation of things. I believe what happened was after she got out of the hospital, I don’t know if she left on her own free will, or if they came and got her after they bailed out, but I think they crossed paths shortly thereafter. Either hitchhiking, whatever it may be, but they crossed paths. They were gonna go to prison, and they beat her again. Except this time when they beat her, she suffered a brain hemorrhage and died. It may have been accidental, but you still put your fist to someone, and there are consequences for that. Law does make leeway for things called manslaughter, where it’s an accidental death. ‘I beat her, but I didn’t mean to kill her.’ It could’ve stopped there. Instead, I believe they took it to the next level, when they went and concealed the body somewhere, and I think they did that while they were down in Bangor, before they even left home.

Robert continues to honor Virginia’s memory in his own way as a beadwork artist. Because of the fire at the trailer, the Pictou family doesn’t have a lot of photos of Virginia. Robert wanted to create something in her memory, so he beaded a 4x6 portrait of Virginia out of about 7,423 beads. He also made one for this dad.

Robert: “I also take Virginia with me wherever I go. Just recently I was at the assembly of First Nations in Canada. They had a gathering for Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls in Vancouver, and I brought Virginia there. I introduce Virginia to the assembly of First Nations chief.”

Robert, like me, wants to humanize the victims behind the statistics. He proposed bringing childhood objects to show the girl behind the picture. For his sister, it would be her tea set. He said, “Virginia would always invite you to her tea and bannock party, and that’s the Virginia I remember. I want to let the world know about that little girl.”

Speaking to Robert, I can feel his passion for his sister and to make a difference more broadly in the MMIW movement. And I believe he will.

Robert: “We can’t stop. We got nowhere else to go. And we’re not going away until we stop... breathing. Because this is our family.”

If you have any information about the disappearance of Virginia Pictou, please contact the Maine Major Crimes Unit North at (207) 973-3750 or toll free 1-800-432-7381. Submit a tip online here.

Visit Robert Pictou’s shop and support his MMIWG2S inspired work.

Connect with Murder, She Told on instagram @MurderSheToldPodcast

Click here to support Murder, She Told

Virginia’s brother, Robert Pictou, as a baby (1964)

Robert Pictou (1966)

Virginia’s brother, Robert Pictou, in stroller, with siblings Carl, David, and Agnes; fields of Fort Fairfield in the back (1964)

Virginia Sue Pictou, age 1, potato houses in back left

Virginia Pictou (~4 years old)

Virginia Pictou (~8 years old, 2nd grade)

Virginia Pictou (~9 years old)

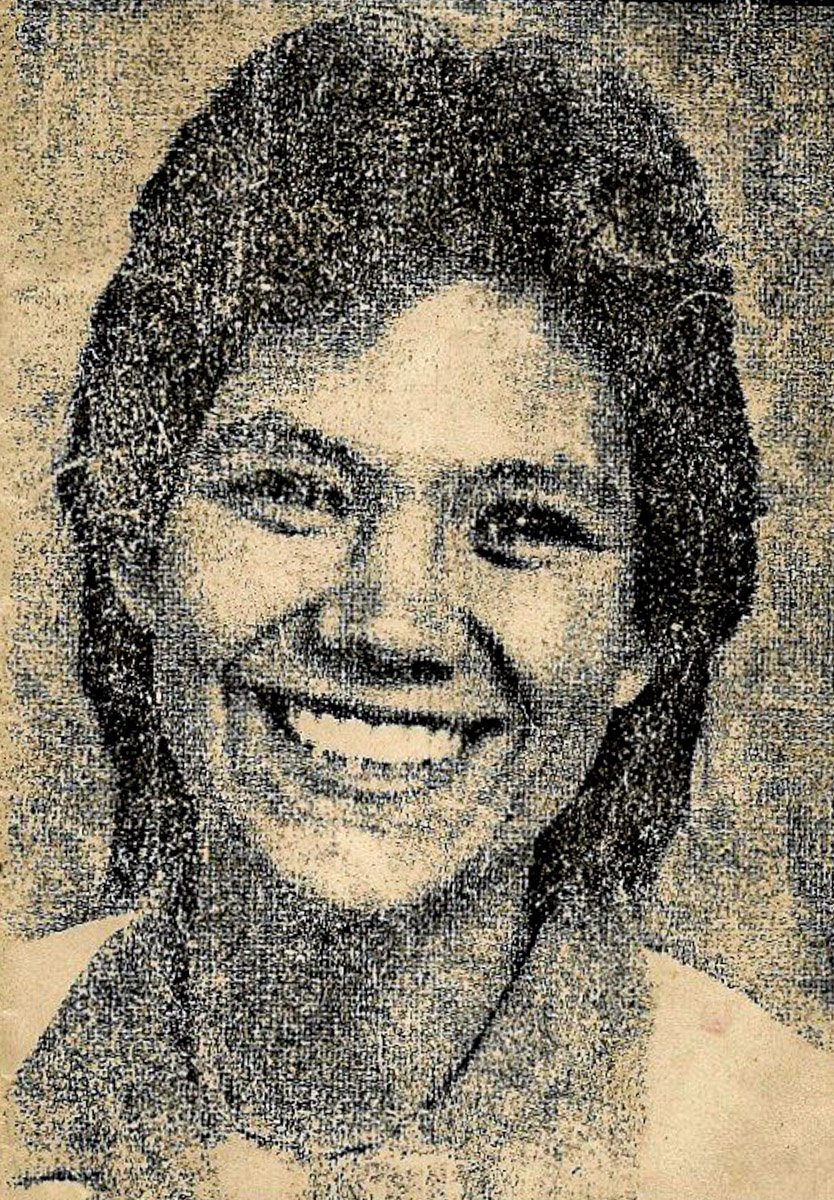

Virginia Pictou (~13 years old)

The Pictou family in Fort Fairfield, Maine

Virginia Pictou (~14 years old)

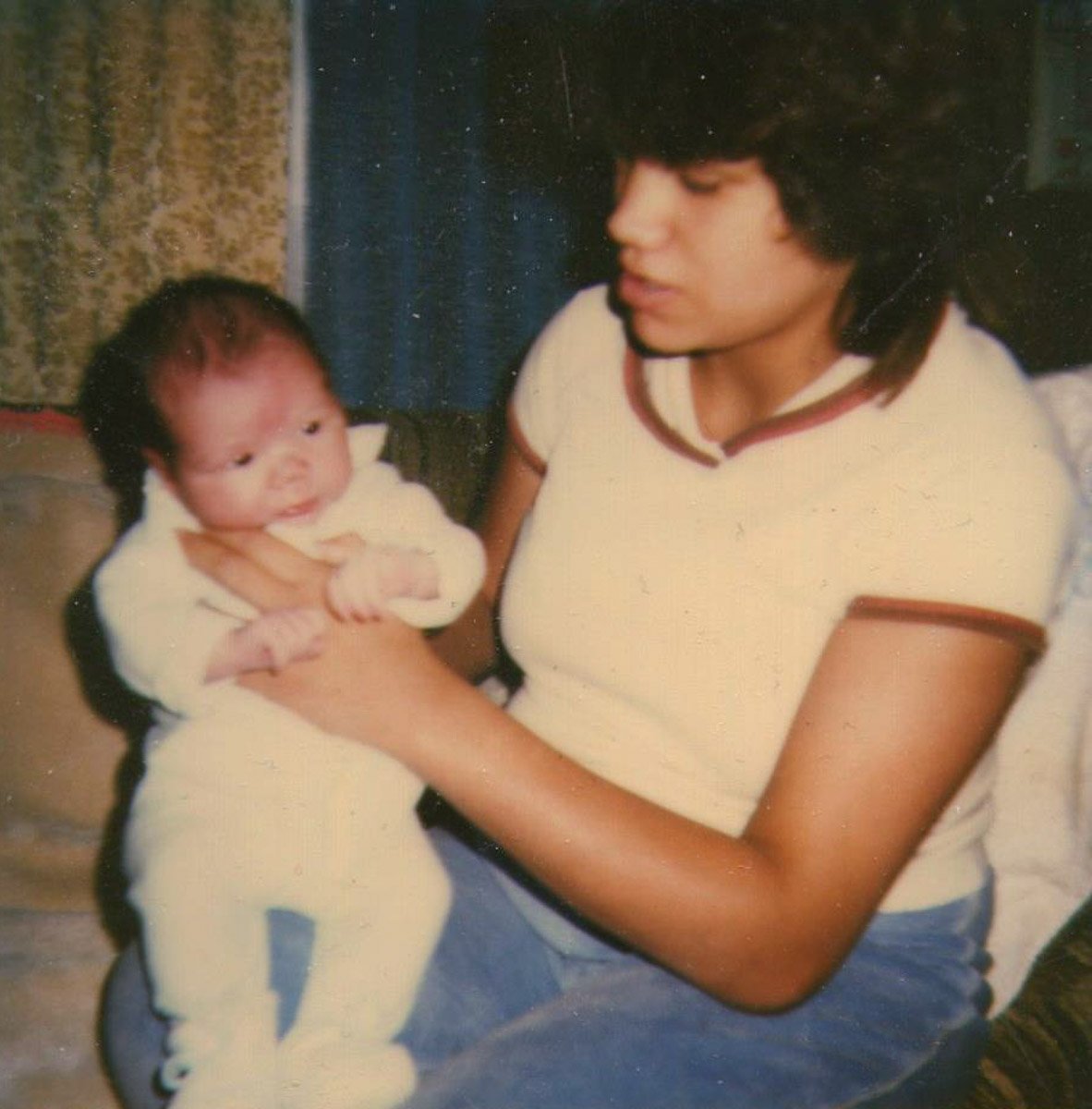

Virginia (~15 years old) with her 1st child, Randy Pictou (~1982)

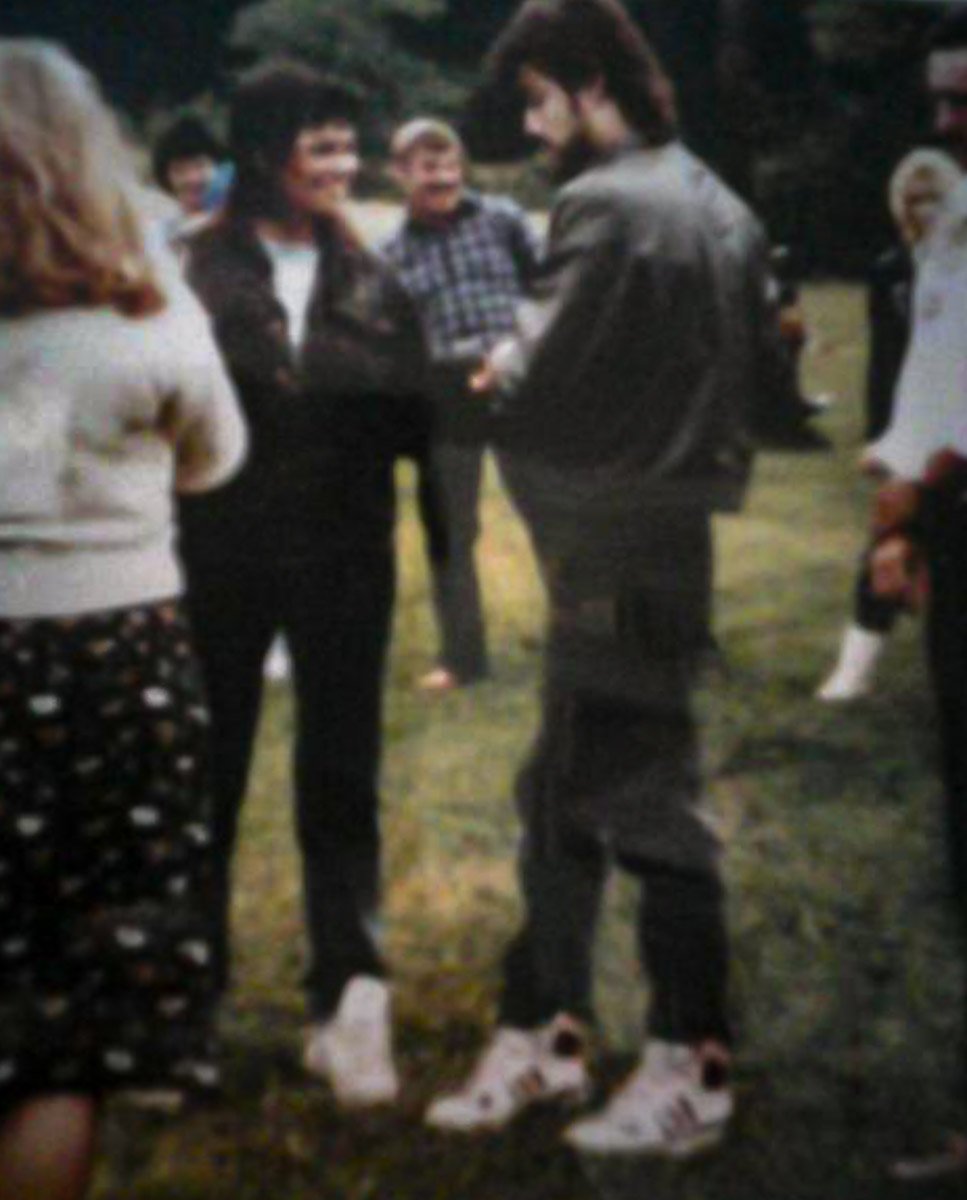

Virginia Pictou (~18 years old) with a friend

Pictou family (1986)

Virginia Pictou with her son Christopher John Pictou (~1985)

Virginia Pictou (~18 years old) at a baby shower

Virginia (~21 years old) with her 3rd child, Ashley Sue Noyes (~1988)

Virginia at a summer camp, she’s center right with dark sunglasses on

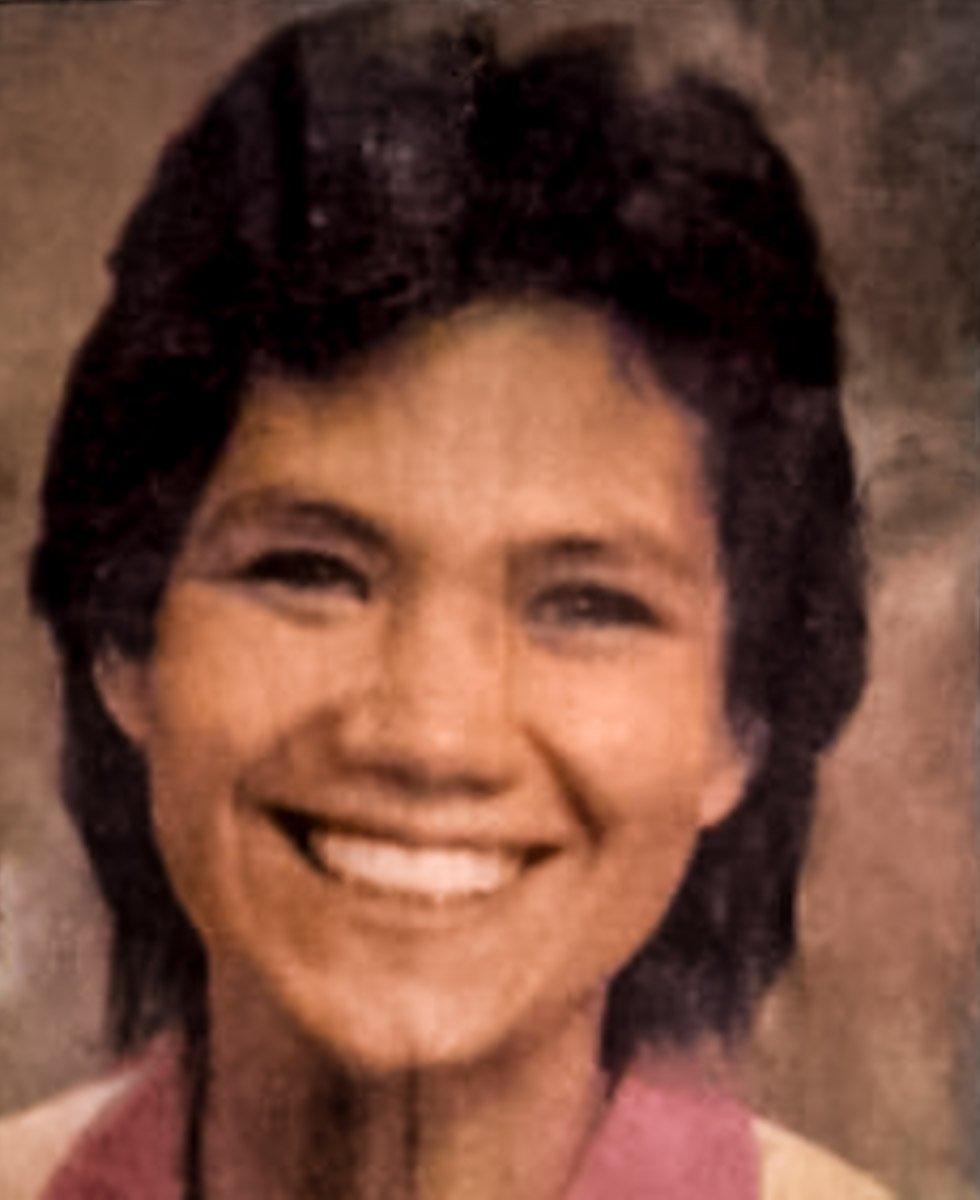

Virginia Pictou Noyes (~25 years old)

Robert Pictou’s wedding, family portrait, Virginia second from left

Virginia Pictou Noyes with Larry Noyes

Larry Noyes

Roger Noyes

Agnes Gould, Virginia’s oldest sister

Agnes Gould, Virginia’s oldest sister, at her radio station

Agnes Gould, Virginia’s oldest sister

Agnes’ artwork in memory of Virginia Sue

Robert Pictou’s beaded portrait of Virginia Sue Pictou

Robert’s artwork in honor of MMIW

Virginia’s father, Robert Pictou, Sr. (center) with actor, Ethan Hawke (left)

Robert Sr.’s phone cover

Pictou family (Top: Robert Jr, Robert Sr, Bottom: Marie, Agnes, Francis)

Agnes, Robert Jr., Francis, Robert Sr. (MMIW national inquiry, Membertou, NS)

Sources For This Episode

Newspaper articles

Various articles from Bangor Daily News, Chronicle Herald, Evening Express, Fort Fairfield Review, Houlton Pioneer Times, Kennebec Journal, Morning Sentinel, St. John Valley Times, and the Sun-Journal, here.

Written by various authors including Aaron Beswick, Callie Ferguson, Christopher Bouchard, Dawn Gagnon, Diana Estey, Eesha Pendharkar, Emma Campbell, Gloria Flannery, Helen Deane, Janice Clark, Judy Harrison, Julia Bayly, Katherine Flannery Finney, KJ Kingston, Melissa Lizotte, Michael Tutton, Tom Harvey, and Walter Griffin.

Photos

Photos from various newspaper articles, Facebook group, and courtesy of the Pictou family.

Interviews

Special thank you to Robert John Pictou for his passion and generosity with his time.

Online written sources

'I-Team: Mother of 7 disappears, still no answers 20 years later' (WGME), 2/21/2016, by Marissa Bodnar

'Missing Mi'kmaq woman Virginia Sue Pictou remembered with beadwork' (CBC News), 4/22/2016, by Molly Woodgate

'Virginia Sue Pictou-Noyes' (The Signal), 12/16/2016, by Rob Csernyik

'Family testifies about pain of searching 24 years for missing Aboriginal woman' (National Post), 11/1/2017, by Michael Tutton

'Families want answers on loved ones, MMIWG commission hears' (The Coast), 11/2/2017, by Maureen Googoo

'Missing and murdered Indigenous women inquiry: We must listen and act' (The Conversation), 11/23/2017, by Jane Arscott

'Maine police investigate claim long-missing Mi'kmaw mother was murdered' (CBC), 11/29/2017, by Jorge Barrera

'Facebook Page Hopes to Find Answers for 24-year-old Missing Persons Case' (WABI5), 11/30/2017, by Ashley Blackford

'Family of missing Easton woman seeks closure after 25 years' (The County), 4/24/2018, by Melissa Lizotte

'Family still searching for answers 25 years after disappearance' (WAGM), 4/24/2018, by Alaina Stewart

'Agnes Marie Gould' (Dignity Memorial), 6/20/2018

'Searching for Justice' (WAGM), 2/5/2019, by Ashley Blackford

'Easton mother missing for 26 years' (WFVX Bangor Fox 22), 4/30/2019, by Susan Farley

'Darrell A. Pictou' (Bangor Daily News), 10/6/2019

'Self-defense classes being taught to bring awareness to Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women' (WAGM), 4/23/2021, by Adriana Sanchez

'‘People are angry’: US families feel let down by Indigenous missing unit' (The Guardian), 4/1/2022, by Hallie Golden

Online video sources

''The hurt is still there': Robert Pictou wants to find out what happened to his daughter' (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC)), 1/1/2018

Credits

Vocal performance, audio editing, and research by Kristen Seavey

Writing, research, and photo editing by Byron Willis

Research by Brittany Healey and Ericka Pierce

Murder, She Told is created by Kristen Seavey