The Murders of Rhonda and Cor’an Johnson

Rhonda Chantel Johnson

Rhonda Johnson was born on November 16, 1977, in Stamford, CT, a city where her family had roots stretching back for generations.

Her parents, Blanche and Jonathan Johnson, did not stay together—sometime during her childhood, her father changed his name to Zuberi Asim Ajamu, a Swahili name that reflected his Muslim faith and African roots. He went by his new middle name, Asim. He eventually moved to New York City, an hour or two away by train. Blanche worked in the ambulatory care unit at Stamford Hospital while raising Rhonda and her brother, Bilal, or “Bila,” as he was called—in an apartment complex on the west side of the city. It was a decent place to grow up; Rhonda’s childhood friend, Jeannette, described it as “a place where everybody knew each other. Everybody was close. You could bring your kids outside.”

Despite her parents’ separation, Rhonda remained close with her father. In 1989, at the age of 11, she went to live with Asim in New York, and would remain there for the next few years.

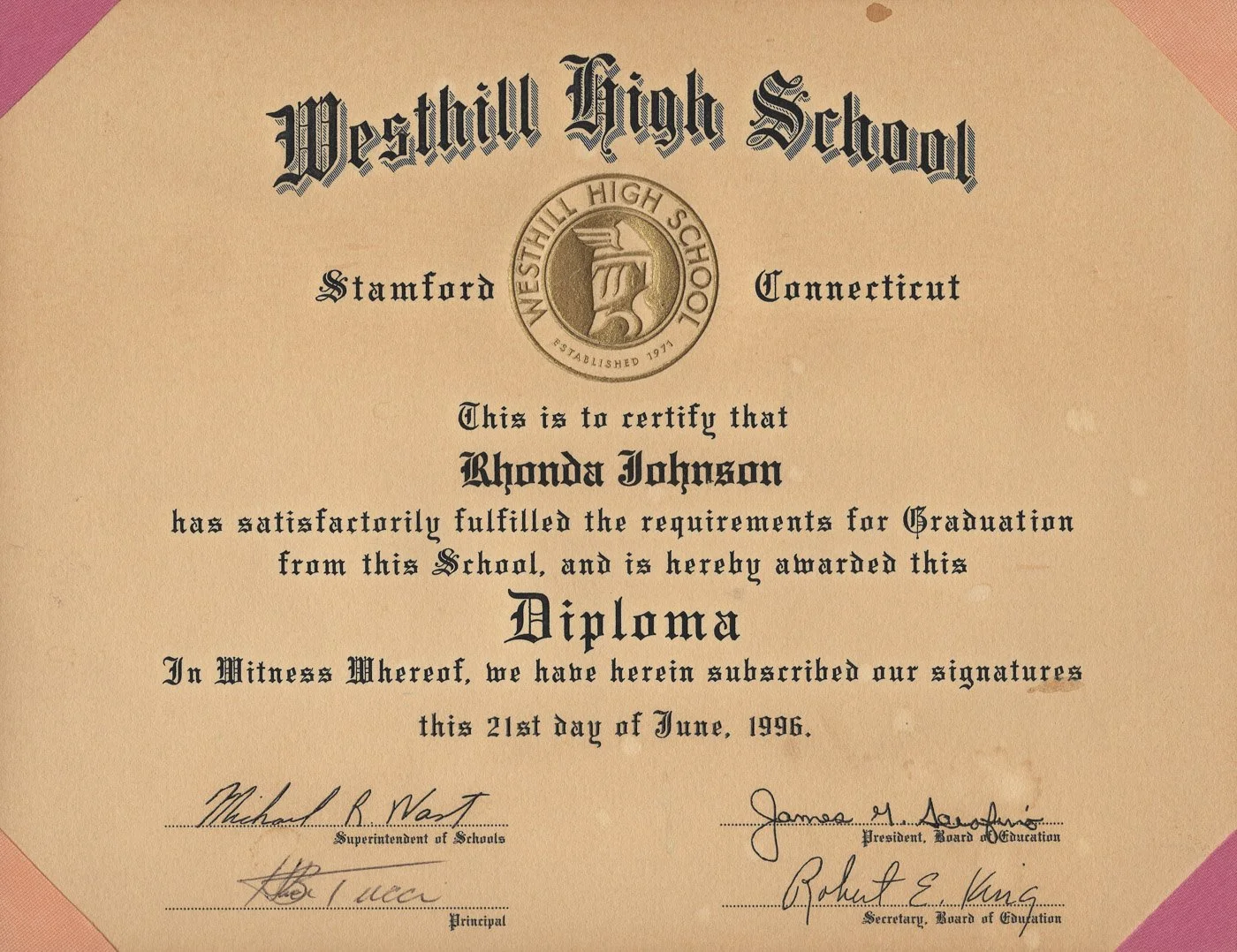

In 1994, she returned to Stamford and moved back in with her mother in a new apartment complex on Bridge Street, now known as “Fairway Commons.” Then 16, she enrolled as a junior at Westhill High School.

Rhonda stayed busy. She was a strong student and a member of the school newspaper staff, as well as Westhill’s multicultural alliance student group. Rhonda had an active social life, including a steady boyfriend. She was known to frequent the parties and hotspots of Connecticut Avenue, Southfield Village, and the West Side. All of that changed when she discovered she was pregnant in the summer before her senior year.

Cor’an Johnson

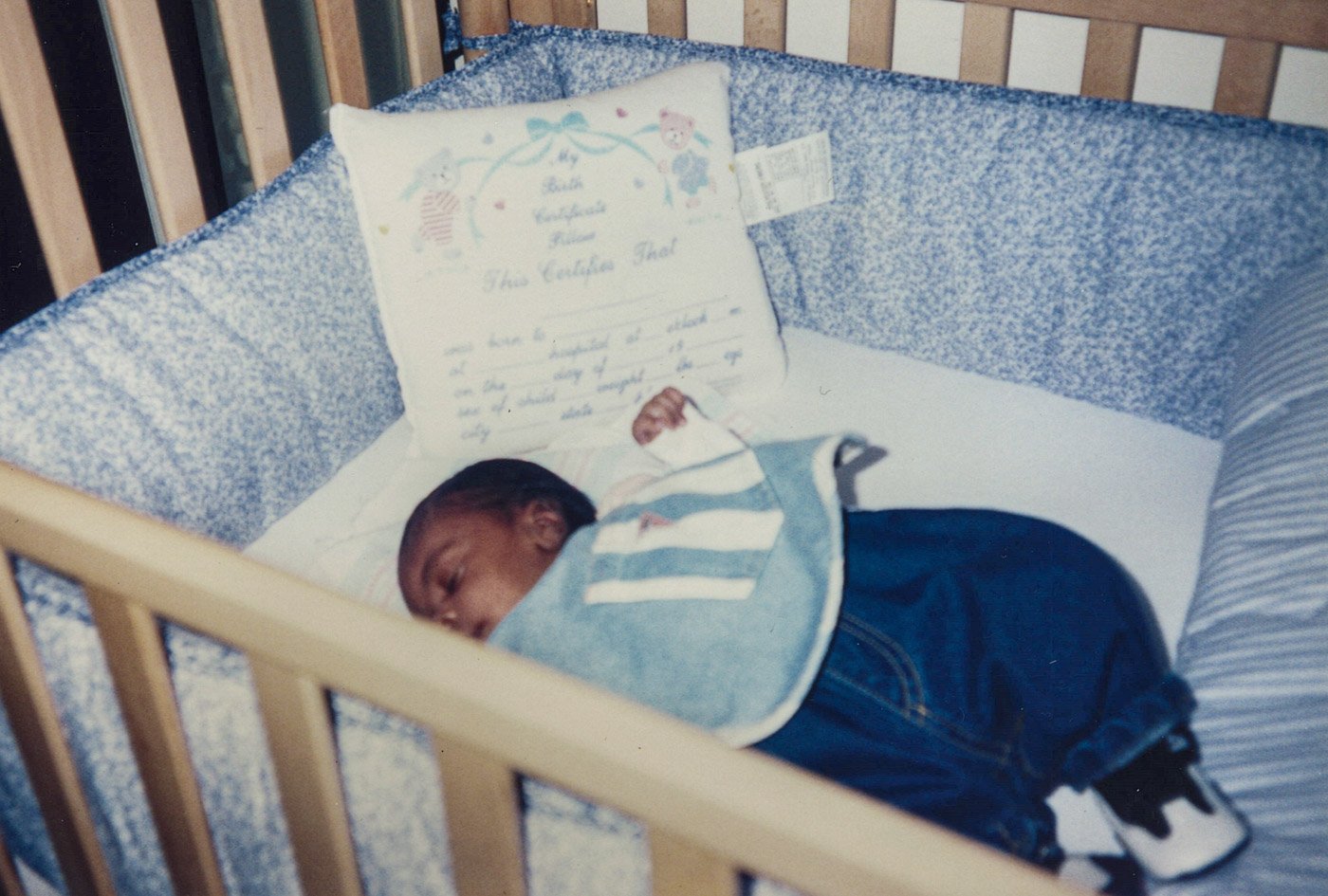

On March 12, 1996, she gave birth to a baby boy whom she called Cor’an.

He was a happy child—Rhonda’s stepmother, Jo Ann, would give him the nickname “Sunshine” to reflect his sunny disposition. Her pregnancy disrupted the first part of her senior year, but not long after giving birth, Rhonda returned to school. Even though Rhonda had many competing priorities, Cor’an was always her number one.

But there was a secret that she was keeping about Cor’an.

During the summer of 1995, Rhonda met up with a young man from her neighborhood named Andre Messam, who was a year older than her. Rhonda had cheated on her boyfriend, and Andre was the father of her baby boy. So, Rhonda told Andre the truth—that he had a son named Cor’an.

We don’t know how Andre felt about the news. He was only 18 and in a relationship with someone else (and had been when Rhonda became pregnant). Other concerns loomed over him—in December, he had been arrested for a drug and weapons charge and was out on bail. But a blood test confirmed his paternity, and he did provide Rhonda with a little financial help. Blanche told the Justice Journal in 2007 that, “Rhonda wanted the baby to grow up and know his dad, but they weren’t going together, and he didn’t come around a lot. He would give her money for the babysitter.”

Rhonda forged ahead with her classes, relying on her mother and other caretakers to watch the baby while she went to school. It was a very busy time.

In the spring, she attended prom and graduated with her class, walking the stage to receive her diploma. She later enrolled at Norwalk Community Technical College, where she took a full load of courses towards a major in communications. The campus was a 20-minute drive away, so she drove her mom’s blue Toyota Camry to get to and from class. Rhonda also worked part-time in the evenings as a dietary aid at Stamford Hospital, the same facility where Blanche worked.

Rhonda and Cor’an’s last day

Summer wore on, and Rhonda was becoming impatient with the big secret. Andre was reticent to tell his girlfriend that he had fathered a child with someone else, and, according to Blanche, he was not thrilled at the prospect of having to financially support Cor’an.

Andre and Rhonda made plans to meet on Wednesday, September 11. He was to give her some money, and they planned to discuss the pending announcement to his parents. Andre called and asked if they could postpone their meetup until the following day.

Thursday, September 12, began much like any other in the Johnson house.

After dropping her son at his babysitter’s home on nearby Connecticut Avenue, Rhonda went about her usual school day. She spent the morning and early afternoon on campus in classes. Around 2:30 or 3:00PM, she left Norwalk in her mother’s Camry and drove back to Stamford. She picked up Cor’an around 3:30PM, buckled the baby into a car seat and waved goodbye to his sitter. This was the last time that anyone would report seeing the pair alive.

At the hospital, Blanche waited for her daughter to arrive. Because Rhonda’s shift began at 4:30PM, Rhonda had only 30 minutes to make the hand off for Blanche to babysit. But on this day, Blanche watched as minutes, and then hours, slowly passed.

Finally, Blanche called a family member for a ride home, and then tried retracing Rhonda’s steps. Blanche became increasingly convinced that they must have been in some type of traffic accident on the way to the hospital. Perhaps Rhonda was hurt and unable to call.

A gloomy dusk had settled over Bridge Street as the sun sank low. Blanche paced the neighborhood, her stomach in knots. Looking up from these dark thoughts, Blanche recognized the figure of a friend walking towards her on the sidewalk. They had the slow, cautious step of someone approaching a wounded animal—careful and guarded. That was when Blanche knew that her daughter and grandson would not be returning home.

Discovering Rhonda and Co’ran

At about 5:45PM that Thursday, September 12th, a resident of Grenhart road was walking home from work when he noticed a blue Toyota Camry parked on Grenhart between Victory and Diaz Streets. This was not unusual, as there was a lane for parking on the side of the road opposite the highway. However, he did notice the driver, a young woman, slumped against the partially-open driver’s side window, motionless. He assumed that she was sleeping, as was the baby he could see in the car seat in the back.

A couple of hours later, just before 8:00PM, a woman walking her dog down Grenhart Road also took note of the Camry and the figure slumped in the front seat. She noticed the lifeless pallor of Rhonda’s skin and the conspicuous silence of the baby in the back seat. Horrified, she hurried home to call the police.

It was not long before the first police officers from Stamford PD reached the Camry. They discovered that Rhonda had been killed by two gunshot wounds to the back of her head. Cor’an, still in his car seat, had been shot once in the temple at close range. No weapons were found in the car or in the surrounding neighborhood.

A community mourns

The next day, Friday the 13th, the Stamford PD interviewed Rhonda’s family, friends, and coworkers in an effort to piece together a portrait of her life and a timeline for the day of her death.

While the police continued their investigation over the next few days, Rhonda’s family grieved. Friends and neighbors arrived at the apartment on Bridge Street to offer their condolences and express their sorrow.

On Wednesday, September 18, just six days after she last saw them, Blanche Johnson laid her daughter and grandson to rest.

Visiting hours were held at Bethel AME Church, a Methodist church on the city’s West Side. Rhonda and Cor’an shared a single coffin, with the baby nestled in his mother’s arms.

The funeral service, held in the early afternoon, drew an overwhelming number of attendees. More than 600 people came to pay their final respects, with 200 or so standing outside in the rain or huddled in the church’s crowded foyer.

Rhonda’s father, Asim, performed the eulogy for his daughter and grandson, making no effort to hide the anger within him. “I pity the fool who killed my babies,” he said. “The man or woman who kills a human being takes on all their worldly sins because they didn’t have time to atone. My babies will go directly to heaven.” He demanded of the crowd, “How (could) some sick human being do that to my babies, to Blanche’s babies?”

When the service concluded, the single coffin was carried from the church by a group of Stamford fire fighters who had volunteered to serve as pallbearers. A line of cars made their way to Woodland Cemetery, a grassy patch of land overlooking the east branch of Stamford Harbor. There, Rhonda and Cor’an were laid to rest.

Afraid to talk

During the funeral, Stamford’s mayor, Dannel Malloy had pledged that the city would work tirelessly to locate the person responsible. 6 weeks after the murders, Stamford PD Lieutenant Frank Lagan spoke with the press, and asked for the help of the Stamford community. He said, “I think it is time for decent people to tell what they know about this... to put aside personal fears and do what is right for the community. Somebody that can kill a 6-month-old... can kill anyone.”

For the most part, Lt. Lagan was tightlipped about the details of the case, refusing to name any suspect. The lieutenant revealed that his team had spoken with four people he believed had firsthand knowledge of the crime, but all four either refused to talk or denied knowing anything.

To anyone who was afraid to come forward, he offered to help protect them—offering to relocate them to another part of the city, saying, “We can work with the Housing Authority if people are scared.” But all he heard was silence.

Andre Messam

While there didn’t appear to be any direct evidence linking him Andre Messam to the crime, Andre surely felt the eyes of the law—and the community—focused on him.

On October 1, 1996, just a few weeks after the killings, Andre was arrested on a number of drug-related charges after a foot chase with police. He was caught with 37 baggies containing a paltry 5.2 grams of crack cocaine and two bags of marijuana.

As a result of his flight, Andre was charged with interfering with the police in addition to six drug charges that included possession of narcotics with the intent to sell and possession within 1,500 feet of public housing. His bond was set at $35,000, and he was released from jail after it was paid.

His next brush with the law came in late March of 1997, when a task force focused on narcotics conducted a search of his apartment. The officers reportedly seized 50 prepackaged, $10 bags of crack cocaine, along with about $1,500 worth of loose crack cocaine. In addition to possession and intent-to-sell charges, Andre also faced the charge of “operating a drug factory.”

His lawyer, Matthew Maddox, suggested that he was being targeted unfairly by the police because of their suspicions about his involvement with Rhonda and Cor’an’s deaths. “He’s absolutely innocent. The child was his child. He had no motive to commit this crime,” he told The Advocate around the 1-year anniversary. “He had even offered his cooperation to Lt. Lagan twice while awaiting trial but received no reply.” Regarding his drug arrests, his lawyer told the paper that, “It virtually amounts to a persecution campaign.”

Both sets of charges—arising in 1996 and 1997—were settled in ‘98. He was sentenced to 92 months in state prison—about 7 ½ years. His attorney, Matthew Maddox, said that the punishment was excessive. Most offenders in Andre’s position, he claimed, would have been sentenced to a maximum of three to five years. “I think the eight-year sentence speaks for itself,” he later told the media in 2000. “It makes me think that he is being punished for an uncharged offense.”

Kenneth Brickhouse

Kenneth Brickhouse was only 15 years old, about to turn 16, on the day that Rhonda Johnson parked her mother’s Camry on Grenhart Road. He is in his 40’s today and has spent the majority of his adult life incarcerated.

During his stint in prison from a 1998 conviction, Kenneth was approached by FBI agents collaborating with the Stamford Police on the Johnson murders. There was a rumor that Kenneth had some information about the weapon used in the crime. He willingly submitted to a polygraph test in December 2000, during which, he mentioned that he had sold a gun to Andre in August of 1996, the month before Rhonda and Cor’an were killed. Andre and his brother Adrienne, he claimed, threatened him to remain quiet.

Not long after his interview and polygraph, Kenneth was released on probation. His freedom did not last long—in March 2001, he was arrested in Norwalk, CT, for leading the police on a car chase and being caught with a handgun in his possession. Later that month, he was arrested again for attempting to sell 30 bags of crack cocaine to a police informant. This time, he faced federal drug charges. In January 2002, Kenneth stood in the US District Court in Bridgeport, CT, to await his sentence.

Also present in the courtroom was Frank Lagan, the lead investigator in the Johnson case, now assistant chief with Stamford PD. He listened as Kenneth pleaded for leniency, perhaps waiting for the young man to reveal more about the gun he sold to Andre—the gun that could have taken Rhonda and Cor’an’s lives. He made no further mention of selling a handgun to Andre Messam in the summer of 1996.

Justice for Rhonda and Co’ran

Years drifted by and the case remained open. A skin of moss grew in the lettering of Rhonda and Cor’an’s grave. The neighborhood where she grew up and where she had planned to raised her son changed, gentrified. Her mother Blanche relocated to a new home, taking her daughter’s toys and scarves with her. Her contact with the Stamford PD slowed to a trickle, and eventually stopped. She resigned herself to the idea that the justice that she and her family will see in their lifetime may not be of the judicial variety.

In 2006, Rhonda’s father, Asim, passed away. Like many family members of victims whose cases remain unsolved, he never had the satisfaction of seeing his daughter’s and grandson’s killer convicted. Asim’s ashes were buried at Rhonda and Cor’an’s grave at Woodland Cemetery.

Stamford Sgt. Anthony Lupinacci, who worked the Johnson case from 2009-2012, also believed that the case was solvable, but needed witnesses or informants willing to step forward. Sgt. Lupinacci told The Hour in 2012 that, “The guys who originally investigated this worked around the clock and gathered a lot of physical evidence, and a pretty solid lead on a suspect. I interviewed the same witnesses and investigated the case with a fresh look on it, and came up with an additional suspect.” In the intervening 11 years, this additional suspect has never been named. With new advancements in DNA technology, it may be possible to go back and find further evidence.

Andre Messam has spent more time in prison than out of it. In 2010, the DEA once again arrested him in a sting that they dubbed “Operation Hammertime,” which targeted 20 individuals dealing narcotics and firearms in the greater Norwalk area. He pled guilty to the possession charge and received a sentence of 105 months with six years of supervised release.

This past summer, in 2023, while on parole, agents from the FBI’s Transnational Organized Crime Task Force purchased approximately 55 grams of methamphetamine from Andre. In July, Andre fled from police who tried to stop him in New Haven. The authorities caught up with him in Newington, CT. He is currently awaiting trial and, if convicted, faces a minimum of 10 years behind bars, with the possibility of a life sentence. But his time will be served in a federal facility, where he will not have to worry about drawing the ace of hearts from a deck of CT cold case playing cards and seeing the all-too-familiar face of Rhonda Chantel Johnson.

If you have any information on the murders of Rhonda and Co’ran Johnson, please call the Stamford Police Department Crime Stoppers Hotline at 203-977-TIPS or email the CT Cold Case Unit at cold.case@ct.gov.

This text has been adapted from the Murder, She Told podcast episode, The Murders of Rhonda and Co’ran Johnson. To hear Rhonda and Co’ran’s full story, find Murder, She Told on your favorite podcast platform.

Click here to support Murder, She Told.

Connect with Murder, She Told on:

Instagram: @murdershetoldpodcast

Facebook: /mstpodcast

TikTok: @murdershetold

Rhonda Johnson, yearbook photos

Rhonda Johnson, at prom

Rhonda Johnson, seated, 2nd from right

Blanche Johnson holding Cor’an Johnson

Blanche Johnson holding Cor’an Johnson

Baby Cor’an Johnson

Parting words from Rhonda Johnson in her yearbook

Rhonda Johnson’s diploma from Westhill High School

Blanche Johnson’s Toyota Camry

Connecticut Cold Case unit files

Sources For This Episode

Newspaper articles

Various articles from Stamford Advocate, here.

Written by various authors including Dan Mangan, David Lopez, Edward Shen, Eric Detwiler, Eve Sullivan, James O'Keefe, Kerry Tesoriero, and Zach Lowe.

Interviews

Special thanks to Blanche Johnson for speaking with us.

Photos

Photos from the Johnson family (scanned and edited by Murder, She Told), Westhill Highschool yearbook, Stamford Advocate, Google Maps and other newspaper articles.

Online written sources

'United States v. Brickhouse' (AnyLaw), 9/14/2003, by AP

'Zuberi Asim Ajamu' (Legacy), 6/15/2006

'Fear of Retribution Blocks Arrest in Decade Old Murder Case' (The Justice Journal), 1/1/2007, by Dawn A. Miceli

'Rhonda Johnson' (FindaGrave), 8/10/2011

'Coran E Johnson' (FindaGrave), 8/10/2011

'Cold Case Chronicles: 1996 murders of mother, son still remain unsolved' (The Hour), 4/28/2012, by Kara O'Connor

'Stamford Woman's Unsolved Homicide Case Featured in Inmate Playing Card Deck' (Patch), 10/21/2014, by Rich Scinto

'Mom, 6-month old son shot in the head. Police have yet to make an arrest…' (Front Page Detectives), 11/21/2021

'Left on a road in Connecticut. Who took the life of Rhonda and her infant son Coran in 1996?' (Newsbreak Original), 10/28/2023, by Mr. Billy

Credits

Vocal performance, research, and audio editing by Kristen Seavey

Research, writing support, and photo editing by Byron Willis

Writing by Morgan Hamilton

Additional research by Samantha Coltart and Brian King

Murder, She Told is created by Kristen Seavey.