The Case of Paula Roberts, Part 2: Philip Willoughby

Philip Willoughby (left), David Willoughby (right)

This is Part 2 of the Paula Roberts case. Click here for part one on the David Willoughby trial.

Dissension in the ranks

Prosecutor Herbert Bunker was furious. He believed that David Willoughby was guilty. He had a strong case, and yet the jury had disagreed. What went wrong?

The day after David was found not guilty, Bunker spoke to the press, and was quoted in the Kennebec Journal as saying he was “dumbfounded” that the state police hadn’t interviewed defense witness Kathryn Blumberg, his alibi witness who placed him at the apartment house at the time of the murder. And that wasn’t his only surprise. The biggest one was the alternative suspect theory that Mo Harrington was responsible for the crime.

Bunker knew that the verdict was going to reflect poorly on his performance, and he was upset. He said, quote, “there’s going to be some bloodletting at the Attorney General’s Office, and it’s going to come down on me.”

The state police felt that Bunker had stepped out of line in venting to the press. The state police and the state prosecutors are on the same team and this type of public outburst revealed internal dissension; a break in the ranks. Bunker’s boss, Attorney General James Tierney, got involved.

Bunker offered his resignation.

The chief public officer for the state police and the attorney general met privately about the outburst, and released a joint statement: “having discussed this matter in full, we are in full accord and look forward to serving the public in pursuit of our identical goals.”

The state police rep added, “I don’t think it’s productive to get into this hindsight-type of nit-picking.”

Attorney General Tierney refused Bunker’s resignation, defending his record of good work, but he did take him up on his request to be removed from Philip Willoughby’s case. Prosecutor Tom Goodwin took the lead in Philip’s trial.

Public outcry

The week after David’s trial was over, a credible threat was made against Judge Alexander, who presided over it. The anonymous caller explained how he was going to come to the courthouse and kill the judge with a handgun. Security was beefed up and guards were on high alert. No one appeared, but it revealed the public anger about David’s acquittal.

David’s attorneys said that he had been “dodging death threats” and left the area to live with his sister, in part to start a new chapter in life, but in part for his own safety.

But they wouldn’t have to wait long to have another shot at justice.

Philip’s trial – Jury selection

Philip’s trial began in Hancock County in the town of Ellsworth, which is perched near the mouth of the Union River, some 2 hours east of Augusta—even further away from the crime than David’s trial. His defense team had requested that it be held far away from the public wrath that might taint the jury pool.

On Monday, November 5th, 1984, less than one month after his stepbrother was found innocent, a group of around a hundred potential jurors filed into the majestic building. Tuesday was a holiday, and on Wednesday, the group had been winnowed to 41 through strategic questioning by the lawyers. Opening arguments were expected to begin on Friday with the expectation that the trial could last up to two weeks when a big wrench was thrown in the works.

Philip’s mom, his stepfather (who had legally adopted him), and his sister Stacy were all called by the prosecution to testify against Philip at the upcoming trial by subpoena. Stacy in particular was classified as a, quote, “material witness”—a legal term meaning a very important one. State police investigators tracked her down in Louisiana and brought her back to Maine just for the trial. The Willoughby family appeared in court on Wednesday and filed a motion to quash the subpoenas because they claimed that they had a right not to testify against their own family.

In general, if you are called to testify as a witness in a trial, you must appear and answer questions on the stand. But there are some exceptions. For example, you can “take the fifth,” invoking your right not to incriminate yourself. If you’re a doctor or a lawyer, you don’t have to testify against your patient or client. And most closely related to the Willoughby’s plight, if you’re married, you don’t have to testify against your spouse.

They said that same right to silence applied to families, and that their private discussions with Philip were not subject to disclosure.

Judge Alexander disagreed. He said no such right existed in Maine state law, and he charged each one of them with criminal contempt of court. It made no difference. He said that they would spend the trial in jail. They still refused to testify. They filed an appeal the same day with the Maine Supreme Court, and the judge agreed to postpone the jail time pending the resolution of the appeal.

The Judge asked the prosecution what they intended to do without these important witnesses, and the prosecution filed a motion to postpone the trial. They needed to regroup.

David leaves Maine behind

While Philip’s trial was in limbo, David moved away from Augusta to live with his sister, who was in York, Maine, and then moved again to live with his brother in Dallas, Texas.

On December 12th, a month after Philip’s trial’s false start, attorneys met with judge Alexander to discuss it and everyone agreed to wait until the Maine Supreme Court had ruled on the family testimony question.

Willoughbys roll the dice

On January 7th, 1985, the highest court in Maine heard the Willoughby family’s appeal.

In a unanimous opinion, the high court said that they wouldn’t rule on a hypothetical scenario. In other words, the trial judge was within his right to deny the motion to quash the subpoena, but the trial judge should not have charged the Willoughbys with criminal contempt.

The Willoughbys “must appear at trial and refuse to testify and risk a finding of contempt. Only upon a judgment of contempt at trial is the issue ripe for appeal,” said the high court. There was no legal basis for enabling a witness to obtain a ruling on family privilege in advance of trial.

The Willoughbys had to roll the dice. Were they willing to take the risk of being charged with a felony and potential jail time to protect their son?

In February, the Willoughbys announced their decision to the press: no matter the consequences, they would not be witnesses for the state against their own family.

“Stir-crazy” syndrome

The new trial’s date had been set, Monday, April 1st, but Philip had been stuck in jail, held without bail, for 15 months, and he was getting a little antsy. He was becoming a little too free about what he was saying to other inmates and correctional officers.

His lawyer got word of it.

The prosecution had interviewed some of his cellmates and jailers, and they learned that Philip had made some self-incriminating statements. The prosecution has a duty to turn over to the defense any incriminating evidence, and when Philip’s attorneys found out, they wanted to put a stop to it.

In March, they filed a motion to suppress the new testimony claiming that Philip was suffering from a psychological condition called “stir-crazy syndrome,” which would make his statements inadmissible. They asked for $1,000 from the state to hire a psychologist to perform an examination. The judge approved $500.

David to testify against Philip

Just a couple of weeks before the trial, prosecutors decided that they wanted David to testify against his stepbrother, so they sent two state police officers to Texas to arrest him on a, quote, “material witness warrant.” He told the police he wouldn’t fight the extradition and would testify at trial.

Philip’s trial

Philip’s trial had been relocated yet again. Instead of Ellsworth, Maine, it had been moved to York County Superior Court in Alfred, Maine, an hour and a half south of Augusta.

On Monday, April 1st, jury selection began, and by Tuesday, 8 men and 4 women had been chosen to decide his fate.

On Wednesday, the defense summarized their case to the jury: “Philip Willoughby did not and could not kill Paula Roberts. This is a whodunnit, and the state doesn’t have the evidence to prove that Philip has done it.”

The prosecution led with their recent revelations from jail: “This is a nasty crime, and I can produce as many as 15 people who heard Philip discuss the murder while in jail.”

The defense countered that those conversations stemmed from fellow inmates taunting Philip.

On Thursday, David appeared in court. The defense petitioned the judge to prohibit his testimony on the basis that his truthfulness was questionable. Judge Alexander cleared the jury from the courtroom and heard David’s testimony privately. He ruled to allow it, saying that he had no overwhelming reason to believe that his statements were false.

“I am making no determination of credibility. That's for the jury. I am not the factfinder in this case. It is not my role to decide in this or any other case which witnesses are telling the truth.”

On Friday, David took the stand and testified against his stepbrother. He said that Philip had borrowed the tan Pontiac Volare to get some beer and came back “hyper, scared, and drunk.” He said that Philip had confessed that “he had robbed a store and couldn’t leave no witnesses.” He recalled how he later discovered the body of Paula, froze, started getting sick, turned and ran.

The same day at trial, the prosecutor played a recording of Philip Willoughby saying that it was David’s idea to rob a store and that following the robbery, David returned home sweaty.

The jury had agreed to meet on Saturday in an effort to get the trial over with, so court convened on Saturday, April 6, 1985.

Two former inmates from Kennebec County Jail (where Philip was held) took the stand. They said that Philip had bragged of committing the murder. On cross, they admitted that he had included some gruesome embellishments to his story that turned out to be false, and Philip’s attorney suggested that Philip had simply lied to his fellow inmates to appear to be tougher.

That same Saturday, Robert, Rita, and Stacy Willoughby were all called to the stand, and they each said, verbatim:

“I respectfully decline to answer on the basis of a privilege and a constitutional right of privacy which precludes me from being forced to testify adversely about my fellow family member.”

The judge threw the book at them. He charged each of them with felony-level criminal contempt, jailed them, and set their bails at $75,000 each. The serious charges would warrant a trial unto itself, but in the meantime, they waited in jail.

The judge then released Robert Willoughby’s grand jury testimony that had been given back in January of 1984 to the public. He ruled that it could not be read to the trial jury, but that the public had a right to know what Robert had said.

The Biddeford Journal Tribune released this statement:

“Robert Willoughby told the grand jury that his stepson, Philip, told him that he and David (Robert’s biological son) had robbed the Summer Haven convenience store in December. Philip told him that it was David who had killed 21-year-old Paula Roberts. Robert said that Philip was ‘deeply involved’ with the crime, but that he believed it was David who had hit the woman ‘with an iron.’”

On Monday, the attorney for the Willoughbys petitioned the Maine Supreme Court to lower their bail amounts, but for the time being, they remained in jail.

On Tuesday, the final prosecution witnesses testified. FBI crime techs spoke about the physical evidence that linked the car and Philip to the crime, and so did a correctional officer from the Kennebec County Jail. He said that he was with Philip Willoughby while he was watching the news on TV. When the story broke about David’s acquittal, he asked Philip what he thought. Philip’s response? “This just ain’t fuckin’ fair because he did most all of it.”

The defense began its presentation the next day and they opened with an audio recording of Philip where he said that David and another man, Kenneth Shephard, had committed the robbery. His attorney was trying to establish that Philip had said from the beginning that it was David who was primarily responsible. But who was this other man, Kenneth Shephard?

Philip took the stand in his own defense. “I’ve never seen Paula Roberts. I never touched her.”

He said that David was responsible, and though he initially fingered Kenneth for the crime, it was actually Mo Harrington who had robbed the store with David. Philip had named Kenneth to protect his friend, Mo. He explained that when David showed him a wad of cash and a class ring with the initials ‘P.R.’, he knew what he had done.

On Friday, April 12th, the lawyers presented their closing arguments to the jury. Lead prosecutor Tom Goodwin pointed out that Philip’s story bore a striking resemblance to his brother, David’s. During cross examination, Philip had admitted that the story was identical, with “only the names changed.”

"There was a tragic breakdown in the criminal justice system in David Willoughby's case," Goodwin told the jurors. "David Willoughby was very much involved in this tragedy and there was an additional tragedy that he walked away free. But there's no way for you to redecide David case. Philip Willoughby is the person on trial here."

Philip’s defense attorney stressed the lack of physical evidence presented by the prosecution.

"I told you in the beginning this was a whodunit.

Philip was wrong to lie to the police in the beginning but the state has not proven that Philip abducted and killed Paula Roberts, or that he assaulted Dixon Smith.

The case is difficult because of the lack of evidence, the lack of tie-ins. There's a gap that can only be filled in by conjecture. Please don't fill it in."

While Philip’s parents sat in jail, he, too waited for the jury to decide his fate.

In three short hours, the jury filed back into the courtroom and delivered their verdict.

Guilty on all counts: murder, kidnapping, robbery, and aggravated assault. The courtroom erupted with a mixture of emotion: another life destroyed, but a triumph for justice.

Bail reduced for parents

As Philip was waiting in jail for his sentencing hearing, his parents successfully petitioned the Maine Supreme Court to reduce their bail. From $75,000 it was reduced to $10,000 each for Rita and Robert; $5,000 for Stacy. They posted bail and were out of jail.

Philip’s sentencing

On May 8th, 1986, Philip returned to face Judge Alexander.

His attorney pled for leniency. He said Philip was “a follower” and “a wimp” who couldn’t have committed the crime himself.

The judge, unfazed by the attorney’s words, read from a prepared statement. He described the evidence as undisputed, and that he believed Philip not only killed Paula, but later went back to desecrate her body. He pointed out that Philip implicated a ‘totally innocent’ man in his initial account to police, but what stunned him the most was Philip’s “total lack of emotion” at the trial.

“When your family members chose jail rather than taking the witness stand out of their love for you, it appeared to me that you couldn’t have cared less.”

He gave Philip a life sentence for murder. In addition to the life term, he gave concurrent sentences of 20 years each for robbery and kidnapping, and a 10-year term for aggravated assault.

Philip, standing tall, with wire-rimmed glasses and an ill-fitting charcoal sports jacket, betrayed no emotion as the judge addressed him, but spoke briefly: “the state used me as a scapegoat for their failure to convict my stepbrother, David.”

He was transferred to Maine State Prison in Thomaston that afternoon. His attorney promised an appeal.

Willoughbys felony contempt trial

A week later, the trial for his family began. They, too, were entitled to a full jury trial. It was conducted in Alfred at York County Superior Court. A different trial judge presided: Arthur Brennan.

The defense cited a precedent set by the Nevada judge and explained that the public’s interest is supported by “fostering open, trusting and confidential communications between parent and child.” Their attorney said,

“How many of us ever thought that sometime we would be called upon to come into a court of law and divulge what was told us — to testify against that person who had come to us for nurturing, for assistance, for guidance, for counseling.”

The state prosecutor countered that the Nevada judge’s opinion was not widely held and was outright rejected by the Massachusetts Supreme Court where it said, “there exists no authority or persuasive policy reason for such an extreme position, and it is this extreme position—an absolute privilege not to testify at all—that we reject.”

But the defense attorney explained simply, “These people aren’t criminals. Philip’s involvement in the crime was a tragedy, but it isn’t right to make his flesh and blood put the nails in his coffin.”

The judge said that it was not up to the jury to decide whether a right to privacy existed amongst family, but merely to decided whether the Willoughbys had broken the law by refusing the judge’s order to testify. The instructions to the jury left little room for opinion about the family’s unfortunate situation to color their views.

Unsurprisingly, the jury quickly found them guilty.

Willoughbys’ sentencing

Two weeks later, on May 31st, they returned to court to face the music at their sentencing hearing.

The prosecutor made a recommendation for a heavy sentence as a deterrent to others who might defy the court.

Judge Brennan sentenced Rita and Robert to 9 months in jail and their daughter, Stacy just 1 month. He explained, “the parents made a conscious decision, and Stacy, who looks to them for guidance, followed.”

Their defense attorney asked that the sentences be temporarily suspended pending an appeal to the Maine Supreme Court. Brennan agreed and allowed the trio to remain free on bail.

Willoughbys appeal to Maine Supreme Court

The Maine Supreme Court later heard their appeal and considered carefully their claim of an intrafamily right to privacy.

Many legal arguments are decided by precedent. The legal system strives to be consistent in the administration of justice, and legal consensus establishes policy. The defense pointed to some examples of a recognition of a right to privacy of family communications in some cases in New York district court and in a federal court case in Nevada, but the prosecution found that every federal appellate level decision and every state supreme court decision had ruled against such a right.

This pretty much settled the matter, but to be thorough, the justices still considered the merits of their argument.

They explained the ethos that guided their thoughts on the matter: the very integrity of the judicial system and public confidence in the system depended on full disclosure of all the facts. And the courts must have the authority to compel the production of evidence—including the ability to punish those who don’t comply.

As they explored the similar privilege of interspousal testimony, the justices were emphatic: in neither the US Constitution, nor in the Maine Constitution could they find any basis for intrafamily testimonial privilege. They said that the only witnesses who could refuse to testify were those that had that exception spelled out expressly in black and white.

Lastly, they challenged the sentence of 9 months, pointing to an old Maine law on the books for “refusing to testify” which carried a maximum sentence of just 3 months. The Supreme Court decided that this old law was an option available to the trial judge, but not a requirement or a limitation of his ability to charge them with contempt and sentence at his discretion.

The three counts of their appeal were all rejected. The decisions of the trial judges involved were upheld.

Willoughbys’ jail term begins

The Willoughbys returned to superior court one final time before reporting to jail.

Their attorney made an impassioned plea to judge Brennan:

“They stood silently when the state compelled them to come forward. They upheld family values of loyalty and confidentiality. They encountered a crisis when a family member told them in confidence about events surrounding Paula’s death.”

He pointed to a Maine journalist who had refused to testify in another Maine murder trial because it violated his professional principles. That man was charged with contempt but was given no jail time—just a hefty fine. He told the judge, “the sentence in that case should give you something to think about.”

The prosecutor told the judge to make example of the Willoughbys: “There should be a message that’s sent out that this type of refusal cannot be tolerated.”

Judge Brennan said himself that “refusing to testify creates the potential for a great deal of chaos, so it’s pretty serious business.”

He did make a concession, though, and reduced the parents’ sentence to 6 months. No change was made to the daughter’s 1-month sentence.

David returns to Maine and ends his life

While the Willoughbys had been focusing on defending themselves against the contempt charges, the state was still dwelling on David Willoughby’s trial (that we covered in part 1), where David was acquitted. They felt he had gotten away with murder.

On October 8th, 1985, exactly one year after his trial, the state charged a witness—Kathryn Blumberg—with perjury. She lived at the 30 North St apartment house and testified in David’s trial that she had seen him there right around the time that the murder was happening.

She was arrested and arraigned shortly thereafter and made $5,000 bail.

Meanwhile, the state approached the US Attorney for Maine about what other charges could be brought against David. After all, they couldn’t try David for murder again because of double-jeopardy laws, but they were looking into the possibility of federal conspiracy to commit murder charges.

David had moved away from Maine, but had returned in the late summer of 1985, and since his return, investigators regularly appeared in his life, reaching out to him for questioning. He could feel their presence, and the pressure of the Maine legal system still weighed on him.

The day after Christmas, December 26th, an investigator from prosecutor Tom Goodwin’s office was paying David a follow-up visit, and he discovered David’s body, lifeless and alone, in his apartment. He was living in Augusta at a Grove Street apartment house. His door was locked, and he was found sitting in a chair, with bottles of pills and alcoholic beverages close at hand. Goodwin later said, “I think it’s pretty clearly a suicide.” The medical examiner agreed, and after the autopsy examination done the following day, he, too, ruled it a suicide. Regarding the conspiracy charges, Goodwin said, quote, “that idea never got beyond the realm of just a possibility.”

About a year later, the perjury charges against Kathryn were dropped. Goodwin said that “they didn’t develop the evidence they expected to find in the investigation.” He discovered that neither David nor Philip were at the house at the time of the murder, but it was not enough to support the charge of perjury. He had to prove that Kathryn knew that she was lying and that she had lied on purpose. Evidently, they didn’t have adequate proof when they charged her initially...

Philip’s appeal to Maine Supreme Court

As promised, Philip’s attorneys appealed his conviction to the Maine Supreme Court, and on Monday, March 3rd, 1986, about a year after his conviction, the seven justices heard his appeal.

The defense appealed five different points about the trial procedure, and the supreme court agreed with Philip on one of those grounds. The judge had disallowed testimony by the psychologist who had examined Philip in the wake of his “stir-crazy” self-incriminating statements in jail leading up to his trial date. The psychologist, Dr. Brian Rines, was prepared to testify about Philip’s tendency to “puff up” or exaggerate his participation. Philip and other witnesses at the jail where he was held all testified that there was a pecking order amongst the inmates that was determined by the severity of the crime. Philip said that he wanted to get into certain cliques by bragging about his crime and saying “anything they wanted to hear.” His jailmates testified about sexual details that Philip had divulged to them that were simply untrue. They also testified about different and at time inconsistent stories Philip had told them.

But the Supreme Court ruled that even if Dr. Rines had been permitted to testify, they didn’t believe it would have changed the jury’s judgment, so they ruled it a harmless error by the trial judge.

On the other 4 counts, they more or less ruled against the defense, and in a unanimous decision, said that Philip did not deserve a retrial.

Philip’s attorneys were still dissatisfied and appealed to the highest court in the land: the US Supreme Court. 7 months later, the US Supreme Court reviewed his case and refused to hear it. Philip had exhausted his appeals.

We looked up Philip Willoughby on the department of corrections, and found that he is MDOC #556, and is currently serving a life sentence. He is 6 ft tall, 390 lbs, has a large bushy brown and gray beard, and a shaved head. He is currently 59 years old. At just 21 years old, in 1984, he was arrested for Paula Roberts’ murder, and he never left jail again, nor will he.

Remembering Paula Roberts

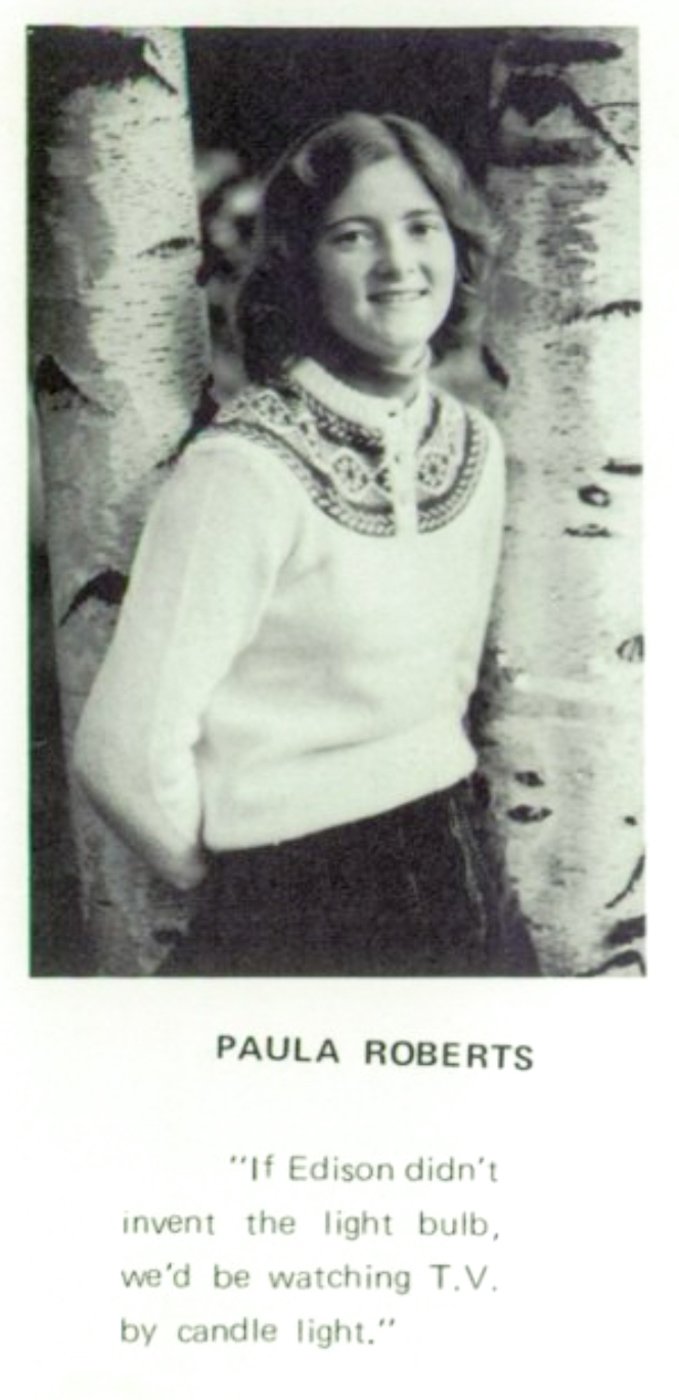

Paula’s life, too, was taken away from her at just 21 years old. She and Philip shared the same birth year: 1962.

She was getting ready to graduate from the University of Maine and begin her adult life. She had the rest of her life ahead of her. It was taken away in a senseless act of violence that was driven by greed and an instinct for violence (stoked by alcohol).

“It wasn’t me”

In telling this story, I can’t help but be reminded of Ashley Ouellette’s case or Ayla Reynold’s. In both cases, the evidence is conclusive that someone in the Sanborn house or in the DiPietro house were responsible for Ashley or Ayla’s death. But who? What do prosecutors do when two brothers are pointing the finger at one another. Who do you convict? Who do you believe?

In Paula Roberts’ case, the car involved was undisputed, but there were three people who had access to that car: David, Philip, and Maurice. It was undisputed that 2 men were involved in Paula’s death. David said it was Maurice and Philip. Maurice said it was David and Philip. And Philip said it was David and Maurice. What do you do when everybody says, “it wasn’t me”?

I can only trust in the prosecution’s judgment not to indict Maurice Harrington. It was only his fingerprints that were not found at the scene. He was never charged with any crime relating to Paula’s death, so I assume that all of the evidence pointed to David and Philip. But that evidence wasn’t enough for a jury to convict David beyond a reasonable doubt. And although there is finality to the situation (because of David’s sudden death), questions still remain. I wonder, today, if we were to ask Philip Willoughby, ‘who killed Paula Roberts?”

What would he say?

Connect with Murder, She Told on instagram @MurderSheToldPodcast

Click here to support Murder, She Told

Paula Roberts and her father (Lawrence Roberts)

Lawrence and June Roberts

June Roberts

Paula Roberts

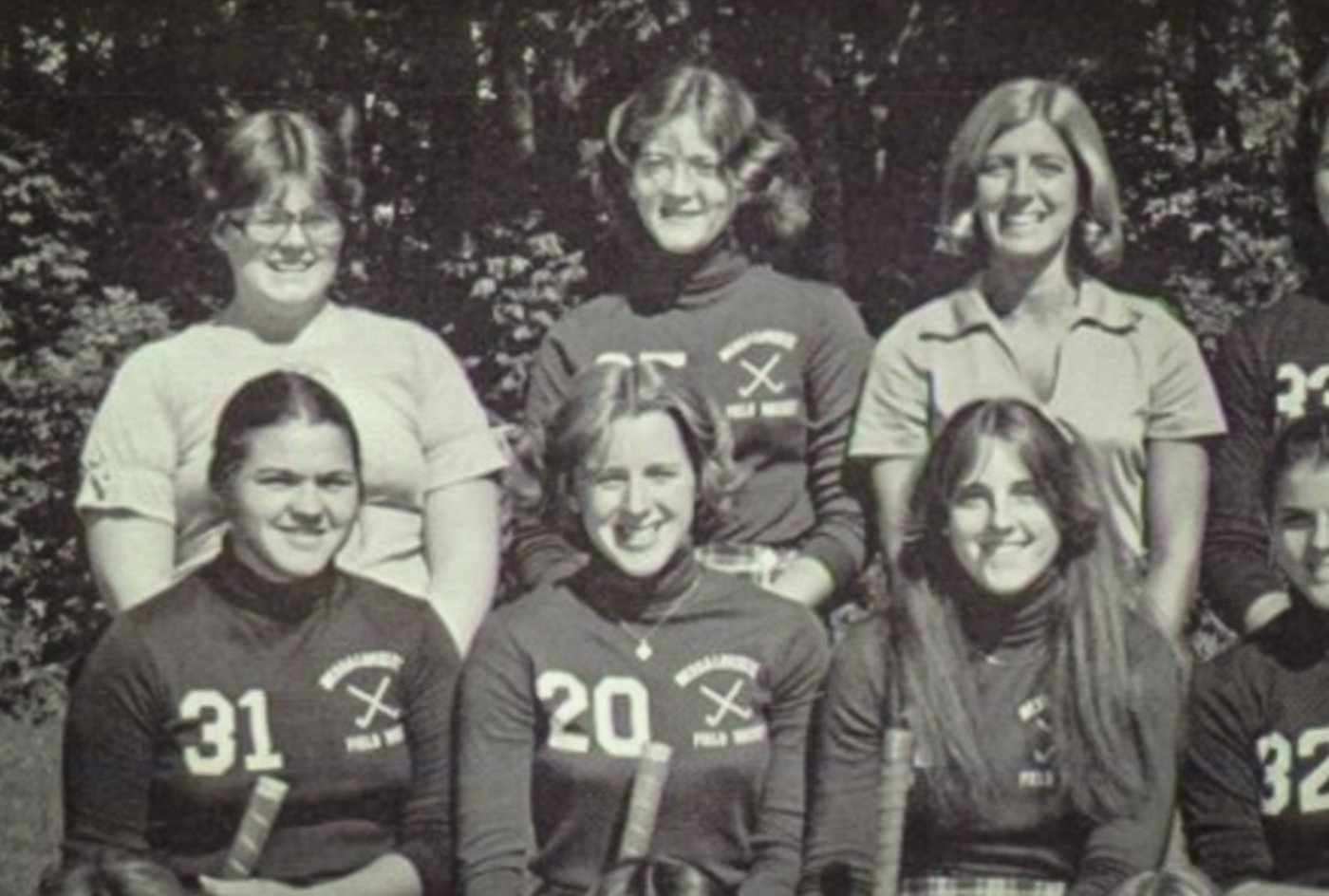

Paula Roberts (with field hockey team, Messalonskee HS)

Summer Haven Ice Cream Shop (881 Civic Center Dr, Augusta, ME 04330)

The search for Paula Roberts in the days following her kidnapping

Paula’s body discovered in Augusta (near 21 Gray Birch Dr, Augusta, ME 04330)

United Baptist Church, Oakland, ME

Lewis Cemetery, Oakland, ME (Paula’s burial place)

David Willoughby, arrested for Paula’s murder

David Willoughby, arrested for Paula’s murder

David Willoughby

David Willoughby, after his acquittal

Apartment house where Philip Willoughby lived (30 North St, Augusta, ME, modern image)

1980 Plymouth Volare (same model used to abduct Paula)

Philip Willoughby (right)

Philip Willoughby (center)

Sources For This Episode

Newspaper articles

Various articles from Bangor Daily News, Biddeford Journal Tribune, The Boston Globe, North Adams Transcript, and The Berkshire Eagle, here.

Written by various authors including Bruce Hertz, Denise Goodman, Emmet Meara, Jean Hay, and Ted Sylvester.

Official sources

Maine Supreme Court decision, Philip Willoughby’s appeal, 4/9/1986, from Justia.com, here

Maine Supreme Court decision, Willoughby family contempt appeal, 10/28/1987, from Justia.com, here

Photos

Photos from various newspaper articles, Google Maps, and findagrave.com (user: Paul Lawrence)

Credits

Created, researched, written, told, and edited by Kristen Seavey

Writing, research, and photo editing support by Byron Willis