The Brutal Murder of Emil Martens

A murder in Wytopitlock, Maine

There was still snow on the ground in the early spring of 1963. On April 10th, a Wednesday, at 9:30AM that morning, Emil went to Clifford’s store and bought some powdered lemonade, though in a later police interview Merle Clifford, who owned the store, said that it was actually two packages of Kool-Aid—either way, a sugary drink—and a few cans of soup. He spoke with Merle for about 15 minutes before returning to his cabin, which was only about 100 yards from the store. Emil was feeling a little sick or hungover—he had just come off a bender. Emil’s habit was to come to the store every 2-3 days to make small purchases—either pea or tomato soup and powdered drink packages. This trip to the grocery and chat with Merle on Wednesday morning is the last time known to police that Emil was seen alive.

The next day, Thursday, April 11th, Merle recalled seeing Emil’s lights on late into the evening. He later told police that they were on at midnight even though Emil typically went to bed right after the 11 o’clock news.

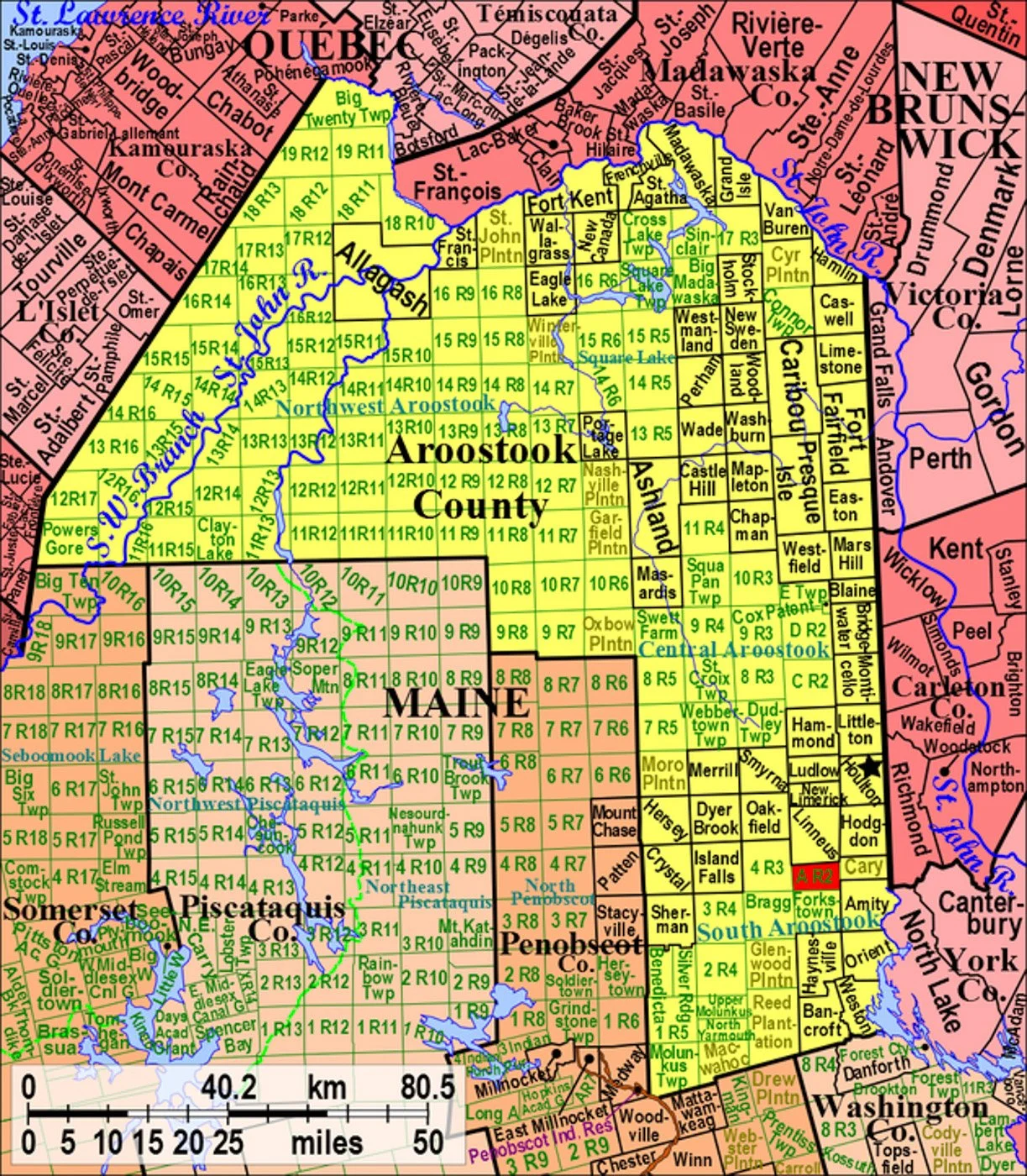

And then on Friday morning a terrible discovery was made. Mitchell Arsenault, a man who lived nearby that was a friend of Emil’s, arrived at Clifford’s store at 8:30AM. Mitchell, who was 80 years old, chatted with Merle for about an hour and a half before moseying on back to Emil’s cabin around 10:00AM. He was gone for about 20 minutes, and when he returned, he told Merle that he thought that Emil was dead. Merle then went to the cabin to confirm what he’d been told, and they both agreed—Emil was gone. When Merle returned to the store, he had his wife call the Houlton barracks of the Maine State Police. Houlton was about 50 miles away, northeast of Wytopitlock. The description of the body suggested foul play immediately, and all the top brass turned up right away to begin investigating.

Nearby state troopers arrived as early as 11:00AM, and others continued to arrive throughout the afternoon.

The first two responders to enter the cabin were Trooper Ronald McFalls and Sergeant James Brown. They found Emil on the floor laying face-down, tied up. His legs were slightly crossed and tied just above the ankles with what was described in reports as “old clothesline rope.” His arms were behind his body and they were tied at the wrists with the same type of rope. His feet were closest to the front door, and his head was further into the room. His head was turned to the left, and his right cheek was resting on the floor of the cabin. A large olive-green bath towel was tied around his head, going around the back of his neck and covering his mouth like a gag, and it was red from all the dried blood. Dried blood covered his hair, scalp, face, and nose. There was a large amount of dried blood on the floor under his head and his upper body. Sergeant Brown wrote that “it looked like he had been moving his head in the blood.”

The body overall was very cold and stiff with rigor mortis. He was fully clothed, except for his right foot, which was bare. He was wearing a heavy, woolen, green-and-black-checkered jacket, and an undershirt. The right front of his jacket and his undershirt were soaked with blood. He was wearing heavy green woolen pants with a black belt. The front of the pants in the area of the thighs had a white substance like plaster dust in the weave. On his left foot, he was wearing a white woolen slipper and an overshoe (or a galosh) atop it. The bottom metal clasp on his left overshoe was open.

Emil had some obvious injuries. First were the injuries to his scalp, which seemed to be the source of much of the blood. Scalp injuries bleed profusely. There was so much blood on his face it was difficult to tell what underlying injuries he had sustained. His mouth was pushed in at the jaw section. His bare right foot had a large abrasion on it, about the size of a tennis ball. They would need to do an autopsy to fully understand the wounds.

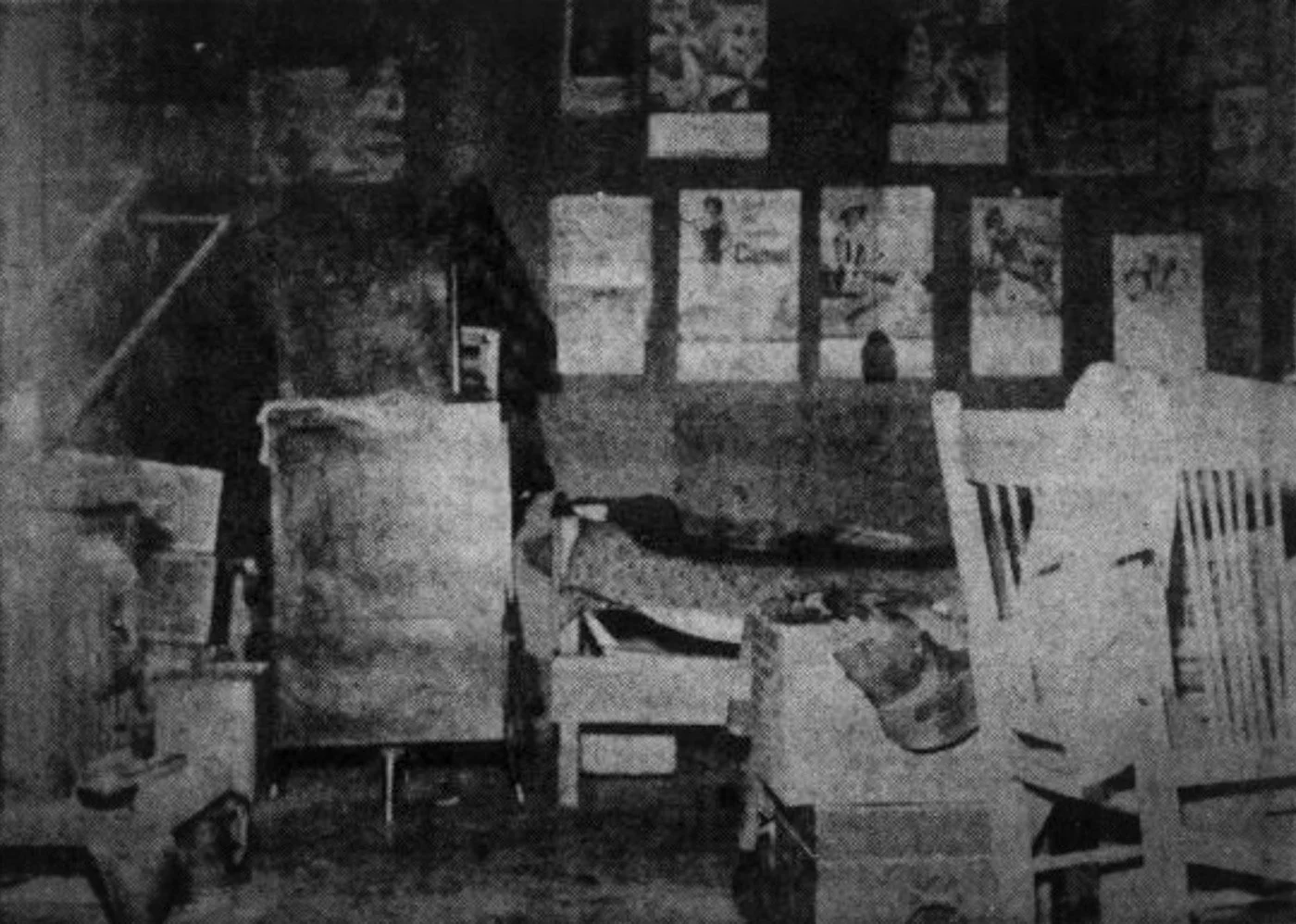

The reports also provide a detailed description of Emil’s cabin. When Merle Clifford entered the cabin, he noticed that the TV set was on, and it “smelled hot,” suggesting it had been on for a long while, so he went to turn it off using the knob. Just before he touched the knob, he thought better of it, and pulled the plug instead, hoping to preserve latent evidence. The light over the bed was on, too. Looking up, above the couch on the walls, he saw that they had been decorated with what he described as “calendar art” (which were pinup models) alongside some family photos. The place was generally in good order except for a chair that had been overturned, a breadbox that was on the floor, and nine broken eggs on the floor next to it. There was a refrigerator with a spot of blood on its door. There were various pieces of furniture and appliances including a washing machine, a wood stove, a table and chairs, and two TV sets. Split stove wood was piled against the left wall. On the table lay the packets of lemonade Emil had purchased Wednesday. The fact that the powdered drink packages were unused suggested to detectives that Emil had been killed on Wednesday night, the evening of the day he had bought them. There was another olive-green bath towel in the room, laying against the east wall, similar to the one that was used as a gag, suggesting that the gag on his face may have been improvised in the moment. On the floor, close to his body, under the kitchen sink, lay his missing overshoe—the one that would go on his bare right foot. A woolen slipper was inside the right overshoe. On the inside of the right overshoe was a substance that appeared to be egg white. He was not wearing his glasses. The left glass in it was broken, and they were on the floor near the wood stove.

Returning to Emil’s body, they searched it for clues. There were long hairs in the knots in the rope that tied Emil’s hands. It’s unclear if Emil had long hair himself, or if these hairs were thought to potentially belong to someone else. They realized that Emil’s watch had stopped. In the right front of Emil’s green-and-black checkered jacket was a splinter of wood that was taken for evidence. It appeared to have come from a piece of stove wood.

A murder weapon was not located, but it was already appearing to some of the detectives that it could have been a piece of stove wood from the stack inside the cabin—an improvised weapon. Police must have found some valuables, because they soon said that “robbery did not appear to be a motive.”

Police took careful note of the condition of the snow surrounding the cabin. The cabin was set back from the road—Route 2A—by a couple hundred yards. The snow had melted in front of the camp and the ground was visible for about 6 feet from the entry door. A roundtrip set of footprints between the cabin and the road suggested that someone had walked from the road to the cabin and returned the same way. The tracks, police believed, were made on Wednesday evening because the footprints had broken through the snow. On Thursday it was quite a bit colder, and it was believed that the freeze would have stopped them from breaking the crust of the surface.

The tracks terminated at Route 2A, and at that location were some tire tracks, which suggested that the unsub had parked a vehicle on the side of the road and then walked to Emil’s cabin. The location of the tracks was described as “300 feet south of the store.” Some particularly clear footprints were identified by police near the road, and they were described as 4 ½” wide at their widest point and 3” wide at the heel. The heel was 3 ¼” long. Unfortunately, our records are cut off and the overall length of the boot print was lost. The length of the stride in the snow, from heel to heel, was 3 feet, 8 inches. The officer described the print as “similar to a rubber boot track.” The gravel was churned up where the car’s wheels were parked, and police determined that the vehicle had left going south. The footprints led to the passenger side door which suggested that there were at least two people involved—the driver and the passenger. A clear right-tire track was identified by police, and measurements and photographs were taken.

And that is the summation of the evidence observed and collected at the scene.

Police investigation

For about seven hours, detectives of the Maine State Police and the Aroostook County Sheriff’s Dept questioned people in the area. Merle Clifford’s wife said that “[Emil] Martens was a drinking man who went on sprees, and he was just coming off a spree.” Emil received Social Security checks, and he had received one for $40 about a week ago, and after receiving a check, he would sometimes go on a binge. Detectives asked everyone about the mystery car parked on the side of the road, likely on Wednesday night, trying to get a clue as to what it looked like, or who it might belong to.

By 7:30PM, Emil’s body had been transported to the town of Danforth at Dunn’s Funeral Home, and an autopsy had begun. Other than Eugene Gormley, the Aroostook County Medical Examiner, there were 12 other men present—all observing the medical examiner’s work. It took three hours, concluding at 10:30PM.

As this was transpiring, other Maine State Police officers secured Emil’s cabin by locking the windows and nailing them shut, and then padlocking the front door.

Autopsy results

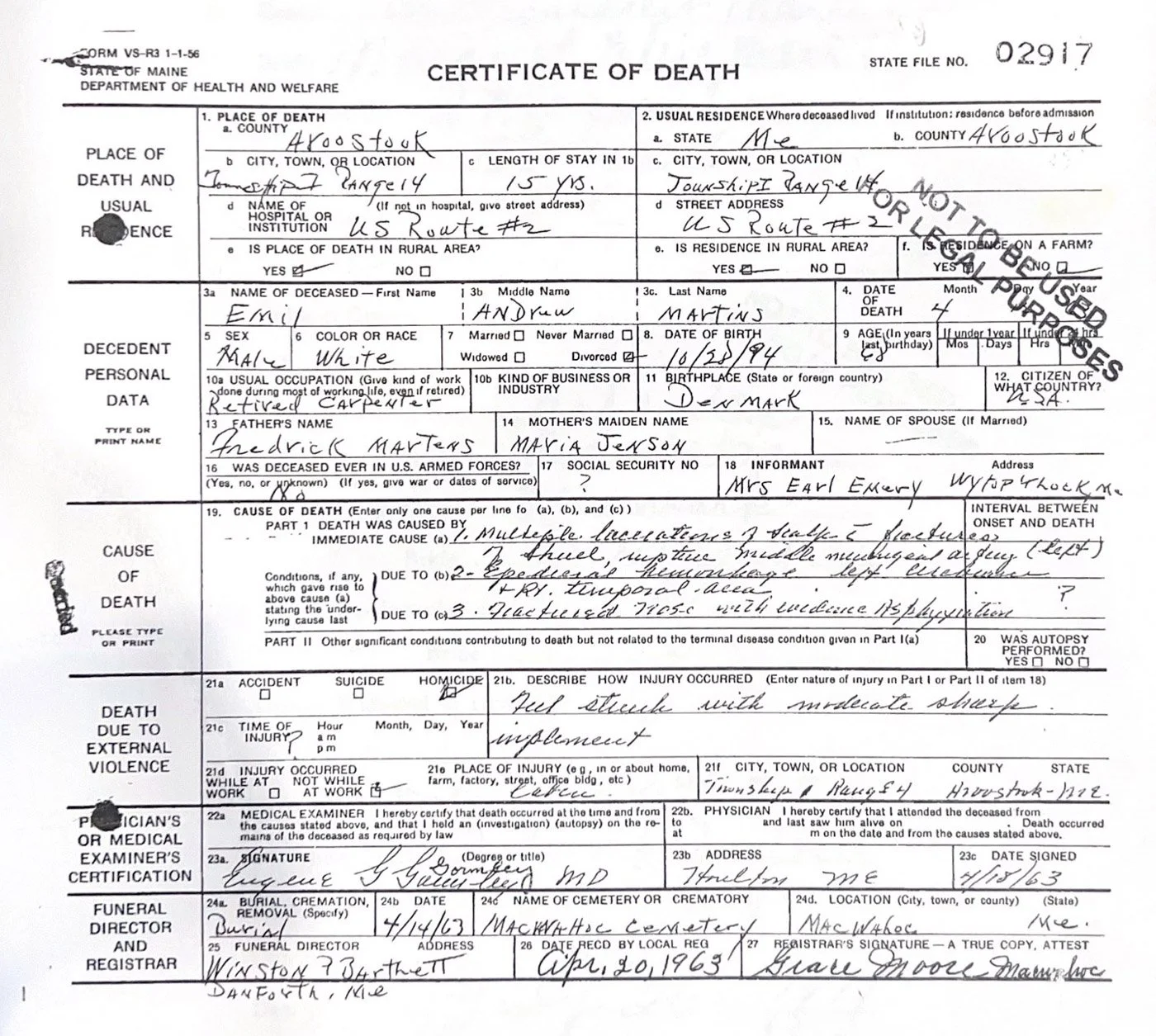

The autopsy determined that Emil’s skull had been fractured. He had been hit on the top of the head four or five times with a sharp-edged instrument which left lacerations two to five inches in length. The ME thought that a sharp edge of split stove wood or the sharp edge of a squared chair leg could have made the wounds. Emil’s nose was broken into many pieces. His left arm was broken, too. The lividity of his body suggested that he died while laying face-down with his right cheek to the floor. His stomach had no food content. There was a large hematoma, or blood clot, found inside his skull, on the left side, which was his likely cause of death. Severe internal bleeding within the skull puts a lot of pressure on the brain. In addition to the head wounds, the fact that there was blood in the whites of his eyes, a covered mouth, and a broken nose, led the medical examiner to conclude that asphyxiation may have played a role, too.

News breaks

The day after Emil’s body was discovered, newspapers around the state all started reported on it. We have articles from the Bangor Daily News, the Brunswick Times Record, and the Lewiston Daily Sun. There would continue to be almost daily coverage on the case through the end of April, after which it falls off dramatically. Early information from law enforcement indicated that the focus of their investigation was on locating the mystery vehicle parked on Route 2A on Wednesday night.

Authorities reported that they were only able to reach one of Emil’s daughters in the immediate aftermath. His funeral would come very quickly. The funeral home in Danforth where his body was autopsied is where his funeral services were conducted on Sunday, April 14th. A local reverend from the Wytopitlock Baptist Church officiated, and he was interred at Macwahoc Cemetery.

Suspects abound

According to police records, all the key law enforcement personnel convened on Saturday morning at 9:00AM to review the details of the case and the direction the investigation was to proceed. There was hope that fingerprints from the cabin might lead to the killer, so they wanted to be sure that they had Emil’s own fingerprints on record to use as a known comparison. One crime scene investigator went to the funeral home in Danforth to obtain fingerprints from his dead body. The rest of the cops continued to canvass the area and establish more information about Emil’s network of friends and acquaintances, and, if known, enemies.

They soon had their hands full looking into the criminal backgrounds and reputations of these people, known to Emil. Captain Edward Marks told the press, “[Emil] associated with many undesirables, any one of whom could be considered good suspect material.” Police soon learned that a party in the area had taken place on Wednesday and Thursday nights, and they began to wonder if Emil had gotten into a confrontation there. Some investigators thought that the incident happened elsewhere, and then he was transported back to his cabin, where he eventually died. But the fact that the television was on, and Emil’s face had been wrapped with a towel, matching one from his own cabin, suggested that the crime had happened while Emil was already home.

A story that came up during police questioning was about a stolen case of beer. Emil had complained many times about a man who he knew well who had stolen a case of beer from some camp, and Emil was fixated on it. He had turned him in for the theft and made threats against him.

But what the police were really after was eyewitness statements—who may have seen the mystery automobile.

A woman who was interviewed by Maine State Police Trooper Ronald McFalls said that she noticed a 1954 Chevrolet sedan that was blue with a white top parked on the side of Route 2A on Wednesday evening around 6:30PM. Another person interviewed by police, who was taking their dog to the vet, passed by Emil’s cabin and then returned the same way an hour later. They, too, described the vehicle as a 1954 two-tone Chevrolet. The Maine State Police found a two-tone, four-door 1952 Chevrolet parked at a residence near where Emil lived. They impounded one of its tires, and its tread evidently matched the tread impressions they had measured and photographed on the side of the road. The owner of the vehicle said that they had acquired the vehicle in January of ‘63—they had traded for it. The man who owned it, whose name is redacted in police records, said that he gave his black ’52 Chevrolet for it. He claimed that he had never been to Emil’s cabin and didn’t know Emil at all. He said that he knew that no one had his car on the Wednesday when Emil was killed. As an alibi, he said that he was out collecting bottles that day. He refused a lie-detector test.

On the Wednesday following Emil’s death, April 17th, police announced that there were three suspects, all of whom had been questioned extensively. Their names were not released. Police also shared that they had returned to the cabin, collected more evidence, and sent some things to Washington, DC for the FBI to analyze.

It was later learned that two men were questioned by police in Aroostook County, and then again by police in Augusta. Eventually the police swapped stories, and it turned out that there were some discrepancies in the stories that the men had told. An arrest warrant was actually issued for the men. They were arrested in Connecticut by Connecticut authorities. Then, in a strange twist, the Maine State Police declined to go get them because they “did not have any money to go to Connecticut.” Aroostook County Attorney John Rogers arranged for the county to foot the bill, but on the day the trip was scheduled, he learned that the state police had called it off. That said, at least one of the men was questioned by Connecticut State Police. He told them that he had left Molunkus, a town close to Wytopitlock, on foot, hitchhiking to Connecticut around the time of Emil’s murder. He said he left at 7:00AM on Wednesday, the day when Emil was believed to have been killed, and arrived in Berlin, Connecticut at 8:30AM the next morning, Thursday, April 11th. He said he’d gotten a ride on a fish truck from Bangor to Berlin. Connecticut State Police were able to corroborate this account with someone else. The man claimed to have last seen Emil in the fall of ’62, about 6 months prior to his death. He had heard of Emil’s death, and he’d also heard that a group of young men, ages 18 to 25, were suspected of being responsible.

On April 26th, the police released a name—the only name they would ever give to the press—Edmund Cote, 60 years old, of Presque Isle. He had served 30 years of a life sentence for murder in Maine and was just released from prison in February. They said that he was “wanted for questioning in connection with Emil’s murder,” and that he was “extremely dangerous.” According to police, he boasted he would never be taken alive. He was eventually caught in San Diego, California, after running a red light, and he was immediately connected to a robbery of a bank in Las Vegas. Nothing further in the newspapers or police records provide more information about this suspect.

At this same point, the police said that they believed robbery could have been the motive, but it wouldn’t have been for more than $10 or $12 (worth about $100 today).

On July 18th, Maine State Police pulled up to the house of Charles Jones, who was from Wytopitlock but was now living in Portland. They wanted to question him about Emil’s murder. As they rang the doorbell, Charles was pulling up in his vehicle. When he saw the cops, he sped away, but police hurried after him. He was 41 years old at the time, and there was a 32-year-old woman in the car with him. During the chase, the car collided with a truck in the heart of Portland. He got a flat tire, but continued on. The papers described it as a “bullet-spattered chase through city streets.” Eventually two tires were deflated, likely shot out by the police, and the car came to a stop at an intersection. Police arrested him on several charges, and he was taken to jail. Police questioned him in jail, and evidently, they were satisfied—the head of the criminal investigation bureau of the Maine State Police in Augusta said that he was cooperative. His involvement with Emil’s case is still unclear.

As summer of 1963 was coming to a close, it seemed that police still had leads, but nothing concrete. They told the press that there were “many suspects in the case” and that some people were under close surveillance.

1969, new witness

6 years after Emil’s death, a strange new witness came forward. He was a truck driver for Merril Transportation, a company out of Bangor, and he claimed to have driven by Emil’s cabin on Route 2A the day of his presumed murder. To corroborate his account, he presented his “truck disc” to investigators—it was an early but reliable tracking method to show speed traveled, distance traveled, and other details about the driver’s route. It showed that he left Houlton at 1:15PM traveling south on Route 2. At 2:15PM, the truck was traveling up Beech Hill, the hill upon which Clifford’s Grocery rested. Just shortly after passing the store he saw a black Chevrolet parked on the side of Route 2A, and saw three men in the back seat of the vehicle, fighting or wrestling. He said the two on the outside were struggling with and beating the third man, who was seated in the middle. In addition to the 3 men in the back, there was another sitting behind the steering wheel. He said he started to stop his truck, but then changed his mind and continued on. He said that he recognized the black Chevy—which he believed was a 1950 to 1952 four-door. He had seen it parked in a yard of a house on the left side of the road, and he said, further, that he had never seen the vehicle again after Emil’s death. The location of the vehicle matched up with where the footprints in the snow had terminated. It seemed like a credible tip. The residence where he had seen the black Chevy parked was about 3 miles from the cabin, but its exact location and the names of its residents have both been redacted.

Case solved by 1973?

The investigation, after 1969, seemed to fizzle out for a very long time.

10 years after Emil’s death, the Kennebec Journal published an article about unsolved murders in Maine. Emil’s name is not even included in the article.

One of Emil’s children, Theresa, contacted the paper to inquire why his name was omitted. She wondered if perhaps the case had been solved, and why she was never notified? The paper printed her letter, which was signed only ‘T.W.’, and answered her question. They had contacted the AG’s office about the matter, and Richard Cohen, who would go on to become the Attorney General of Maine in a few years, said that the list only included murders after 1965. He said that “his department is presently gathering older cases to see if they should be reopened,” which included Emil’s case. This was a fairly direct admission that nothing was being done on the case, nor had anything been done, since 1969.

Modern investigation

From 1993 to just the last few years, the case remained dormant.

But thanks, we believe, in large part, to Emil’s young friend and neighbor, Gerry Clifford, his case was reopened by the Maine State Police.

Gerry was returning to the area after decades away, and he always wondered what had happened to his old friend. He began posting about the case on a Facebook group dedicated to Wytopitlock news. He started talking to old friends and acquaintances who remembered Emil’s name. He spoke to us about the case.

It’s unclear in what year, but sometime in the last 3-4 years, the Maine State Police took another close look at Emil’s case, and I believe they now know who did it. We spoke with Detective Chad Lindsey who worked on this modern reinvestigation. He was willing to speak freely with us if he were given the opportunity, but the Maine State Police, likely directed by the AG’s office, have decided to keep whatever new information he has from the public.

Emil’s family, his grandchildren and great-grandchildren, still want to know what happened to him.

Postscript

We drove out to Mattawamkeag with ambitions of speaking to a man who we’ve heard from credible sources has a story to tell. He is 75 years old now, so he would have been a teenager when Emil was killed. We knocked on many doors, including the one where we believe he lives, but were unsuccessful at reaching him. We still hope to reach him and may provide an update to this story in the future if we do.

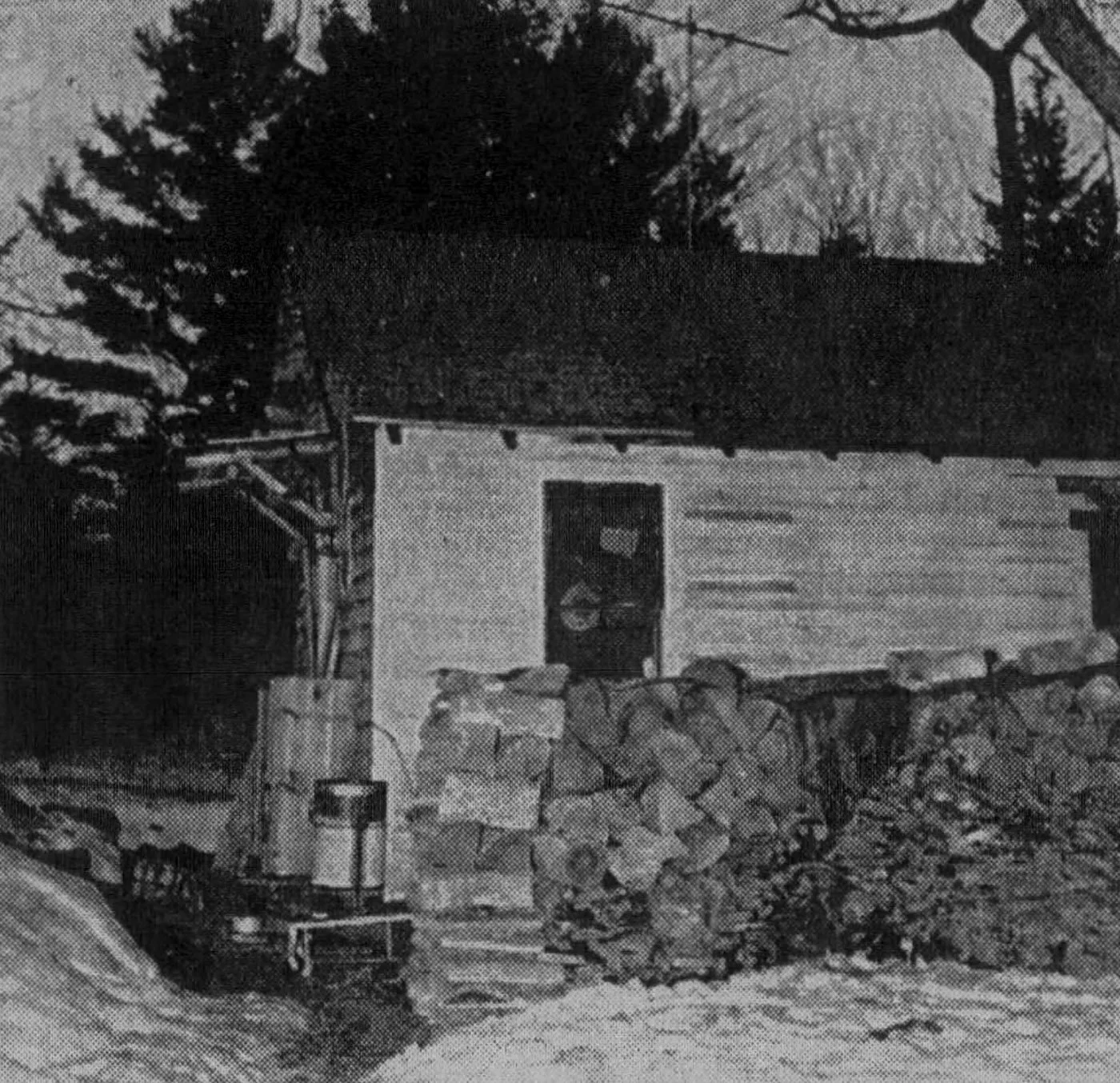

During that same drive, we went to the site where Emil’s cabin formerly stood—on the pinnacle of Beech Hill. Clifford’s Grocery Store is still standing, though it is now used as a residence, and the current property owners were very kind to us, walking through the deep snow to where Emil’s cabin once was. All that remains there now is an outhouse (photo below). We have heard that Emil’s cabin was, years ago, jacked up and transported to some other location. Emil was a fine carpenter—it may still be in use by some family out in the Maine woods.

Though Emil had his faults, he was loved by his family, and he has friends who still talk about him today, 131 years after his birth. These instances that have made the public record about Emil are the negative highlights of his life. What we don’t have are all those moments in between. His wife is gone. All of his children have died (the last of whom passed in 2015). We do not have those first-hand accounts to provide a more thorough picture of Emil Martens.

In his later years he led a quiet life, living in a cabin in the woods of Maine, but violence found him. And despite a flurry of police activity in those initial years, the case was buried in the archives—nary a public mention by a Maine media company or police agency in decades. It is for cases like these that I started this podcast—to remember these murder victims, to support their friends and families, and to bring these stories to a modern audience. Gerry Clifford told us that he often visits Wytopitlock Cemetery in the spring and puts flowers on Emil’s gravestone.

But as those flowers wilt and the moss and lichens cover his name, I think of the dark shadow cast by a lifetime of hard living. I think of him raging against his captors... raging, perhaps, against himself. I think of his final moments and wonder... Did he know his killers? And if he did, did he know, then, why he was being killed.

But whatever the reason, murder is, by definition, without justification, and Emil was murdered. And an imperfect victim is a victim yet.

There was no lucky break in this case, no deathbed confession. This story has no happy ending. This story ends with a sobering truth: his killers have escaped justice.

Continue Emil’s story: Listen to the podcast episode. This text has been adapted from the Murder, She Told podcast episode, The Brutal Murder of Emil Martens. To hear Emil’s full story, find Murder, She Told on your favorite podcast platform or listen on the player at the top of the page.

Click here to support Murder, She Told.

Connect with Murder, She Told on:

Instagram: @murdershetoldpodcast

Facebook: /mstpodcast

TikTok: @murdershetold

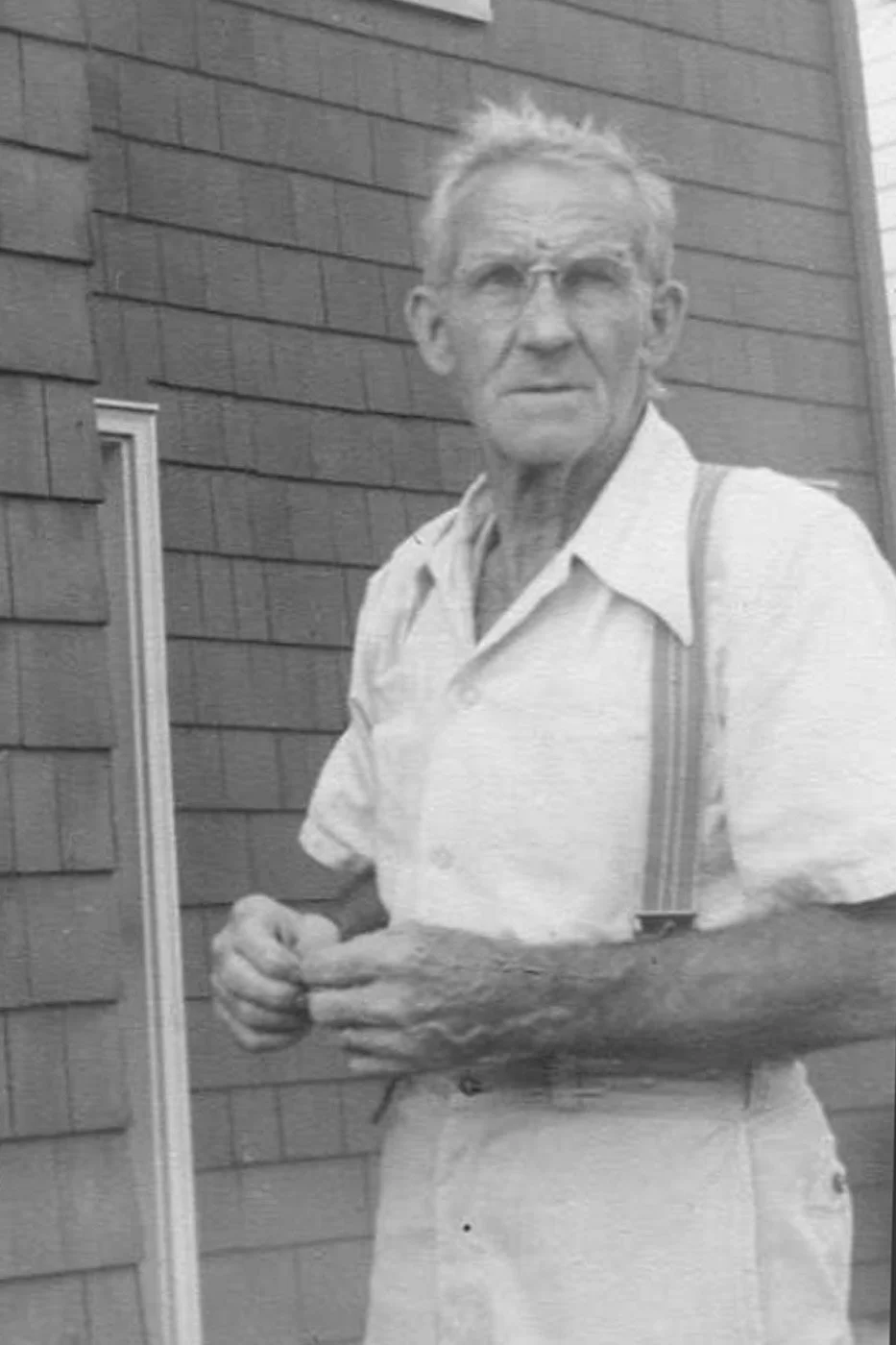

Frederick Carl Martens, Emil's father (Joergen Jorgensen)

Emil Martens, ~10 years old, right, and mother, father, and sister Anna, ~1905

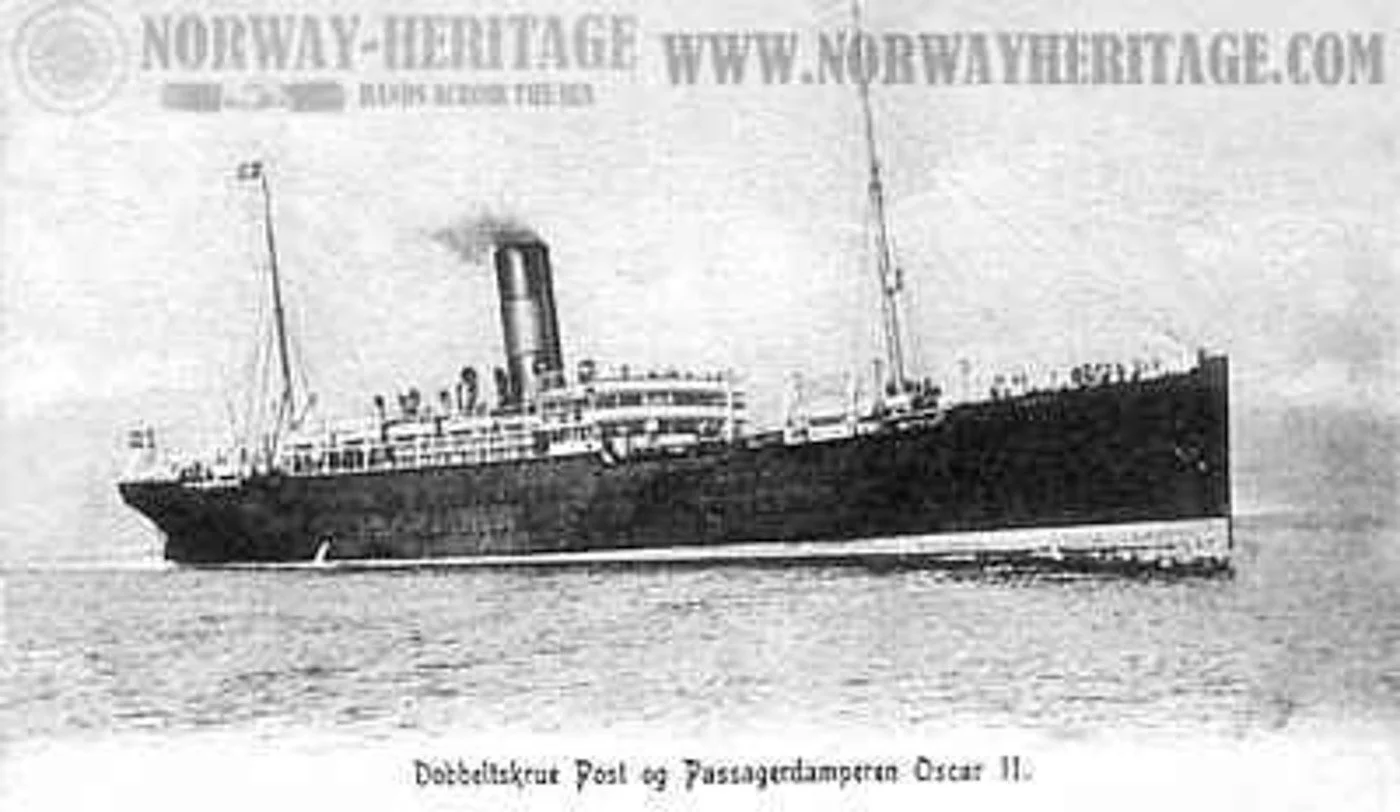

Oscar II, the ship on which Emil sailed to the United States from Denmark

Oscar II, the ship on which Emil sailed to the United States from Denmark

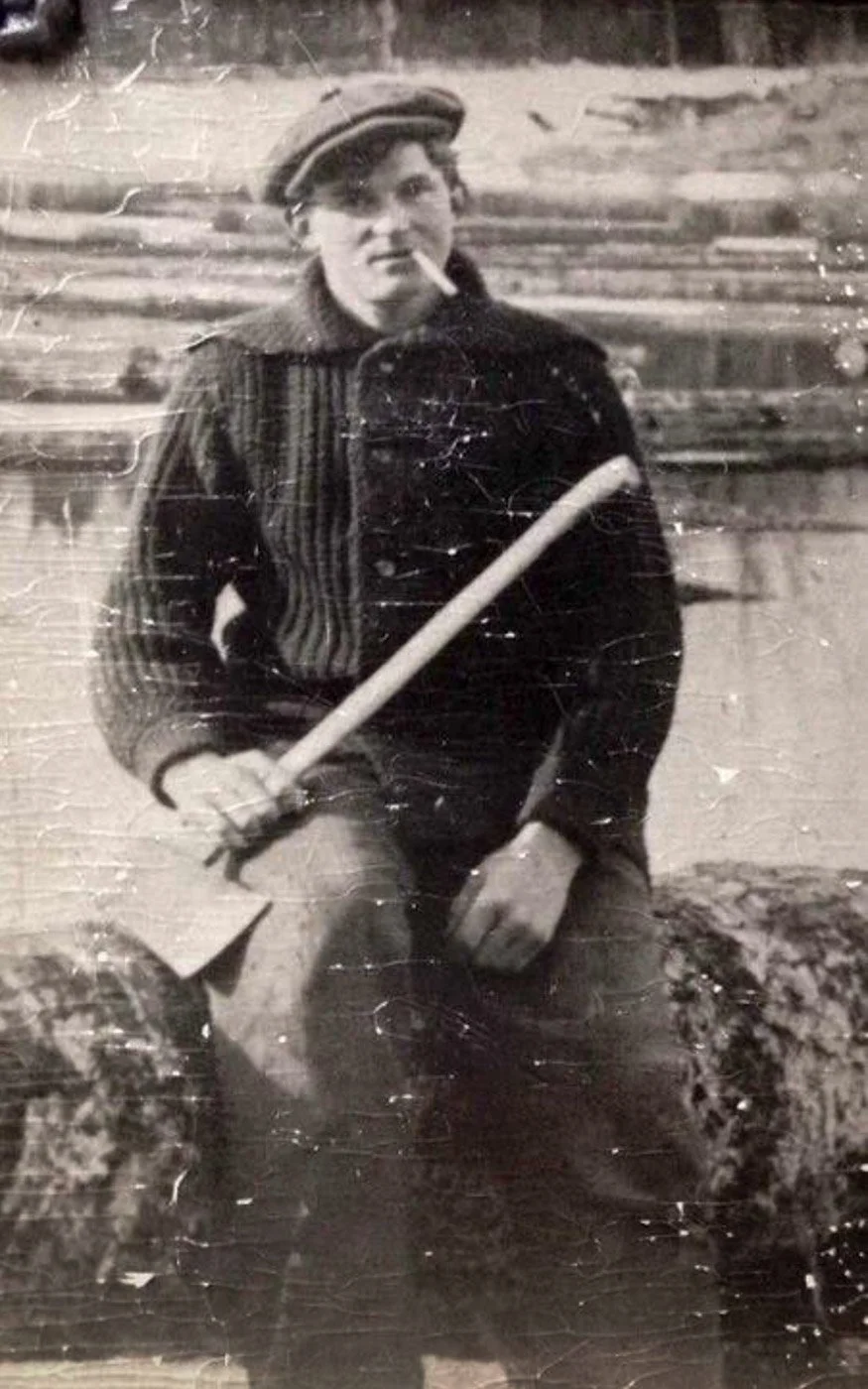

Emil Martens, ~20 years old, (ancestry.com)

Emil Martens, ~20 years old, colorized by Murder, She Told (ancestry.com)

Emil’s draft registration card, June 1917

Emil’s draft registration card, June 1917

Emil Martens, ~58 years old, Joan, Bill, Maggie, Nov 28, 1952 (Emery family)

Judith, Joyce, Carla, Emil's grandchildren (Emery Family)

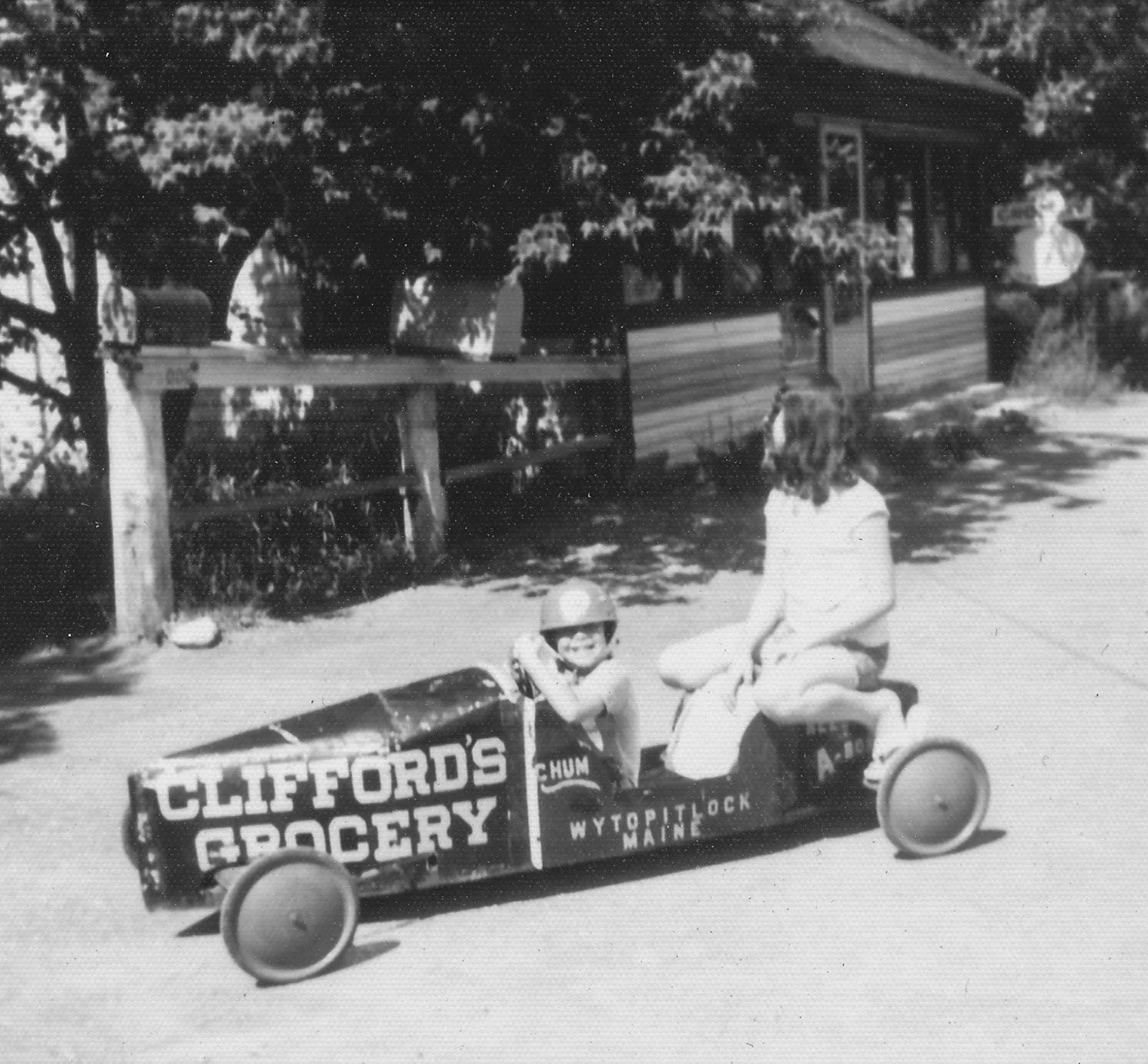

Gerald Clifford with his soapbox derby car that Emil helped craft (Facebook)

Merle Clifford and dog, Skish (Facebook)

Emil Martens, ~66 years old, with granddaughter Lillian, left, and daughter Theresa, right (Bangor Daily News)

Emil’s cabin, exterior (Bangor Daily News)

Emil’s cabin, interior (BDN)

Outhouse between Emil’s cabin and Clifford’s Grocery, still standing today in 2026 (Photo by Murder, She Told)

Emil Martens, death certificate

Sources For This Episode

Newspaper articles

Various articles from Bangor Daily Commercial, Bangor Daily News, Biddeford-Saco Journal, Boston Record American, Evening Express, Kennebec Journal, Lewiston Daily Sun, Morning Sentinel, Portland Press Herald, Sun Journal, and Times Record, here.

Written by various authors including Bob Drew, Ken Buckley, Louis Barrows, Pat Sherlock, and Wayne Brown.

Online written sources

'Emil Andreas Martens' (findagrave.com), 8/11/2018

Where in the world is Wytopitlock (facebook.com), 3/31/2015

Official documents

History of Emil Martens, by Joergen Jorgensen

1963-04-12 - Autopsy report

1963-04-20 - Death certificate

1963-1964 - Case file from the Maine State Police

Interviews

Many thanks to Hilary and Bill Emery, Gerald “Gerry” Clifford, and Det. Chad Lindsey, MSP.

Photos

Photos as credited above.

Credits

Research, vocal performance, and audio editing by Kristen Seavey

Research, photo editing, and writing by Byron Willis

Additional research by Chelsea Hanrahan and Ericka Pierce

Murder, She Told is created by Kristen Seavey.