Cape Breton Three: The Boys on the Tracks

A train strikes three boys who were lying on the tracks

In the early morning light of July 10th, 1970, a freight train chugged along its usual route on the Bangor & Aroostook Railway Line in the wilderness of Smyrna Mills, Maine, 15 miles from the Canadian border.

Its powerful locomotive pulled 19 rumbling boxcars along at a brisk 40 mph, and its heavy steel wheels thundered down the tracks.

Despite the roar of the massive machinery in the Aroostook Wilderness, the trees were sleepy and peaceful – a dewy summer morning in Maine. The only wind present was that created by the passing train. A typical morning on a typical route from Oakfield to Caribou.

As the train rounded a bend near Timoney Crossing, the conductor, Earl Capen, and on-board fireman, Ralph Fowler, spotted some debris on the tracks. Earl squinted trying to get a sense for what it was. It looked like a rubber raft.

Suddenly Ralph’s shouting broke his contemplation— “Sleeping bags! They’re sleeping bags!” he screamed.

Earl blasted the horn, but the sleeping bags were totally still.

With 150 feet to go, Earl frantically slammed on the train’s emergency brakes— hot steel screeched and sparks flew as the brakes worked in vain to stop 800 tons of steel machinery.

But it was too late. The train couldn’t stop, and all 19 cars ran over the three sleeping bags along with the people inside them.

The caboose finally came to a stop a few hundred feet after the point of impact.

The scene behind the train was something out of a horror movie: dismembered and crushed body parts strewn about on the grass and upon 100 feet of tracks, belongings and clothing shredded to pieces, tossed into the woods from the force of the train or dragged down the tracks.

Police contacted, arrive shortly

The train personnel contacted dispatch over the radio, and they alerted the police.

Local PD showed up and began the difficult task of trying to identify the victims. There appeared to be 3 men that they estimated in their 20’s; two of whom were completely unrecognizable, and they couldn’t find any of their ID’s.

Along with some Canadian cigarettes, police found some of the boy’s other possessions scattered near the tracks: Canadian canned goods, maps, camping equipment, and a piece of paper—bloody stationary from a New Brunswick motel. One of the victims had a wallet with a few Canadian bills in it—maybe $5 worth—and another had an empty Canadian envelope. No ID’s were found.

Police discovered a clue from the tattered sleeping bags: a hand-sewn label. It read Thierry Burt, 54 Connaught St., Sydney, N.S. confirming what they had already suspected: the boys were from Canada… likely Nova Scotia.

Two of the victims had long hair and wore beads. Hippie types, Deputy Socoby thought. The Aroostook County Sheriff’s Department reached out to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to help identify the boys.

Autopsy, boys’ bodies destroyed

In the meantime, their bodies were moved to Houlton—to Dunn’s Funeral Home—where they awaited an autopsy ordered by county district attorney Rogers.

The next day, on Saturday, the local medical examiner and the Sheriff of Aroostook County, Darrell Crandall, gathered in a clinical room, brightly fluorescent-lit, to perform the grim task ahead.

They began with the boy whose body was in the best condition. They believed he had been a teenager. He had light brown hair, about 8 inches long. The right arm was broken, white bone protruding from the compound fracture of his upper arm. The right lower leg was badly broken at the shin, the two shin bones clearly visible. All of the bones at the base of the skull were broken. The left shoulder was dislocated. Skin was torn, and there was bruising on the entire body. In other words, a rag doll, misshapen and deformed by the powerful locomotive.

The second boy’s body was in an even more savage state. The head was almost completely severed; the face was unrecognizable. Both the left arm and left leg had been sheared off by the train.

The third boy’s condition was comparable to the second – mangled and disfigured, brought to the funeral home in pieces.

Boys identified

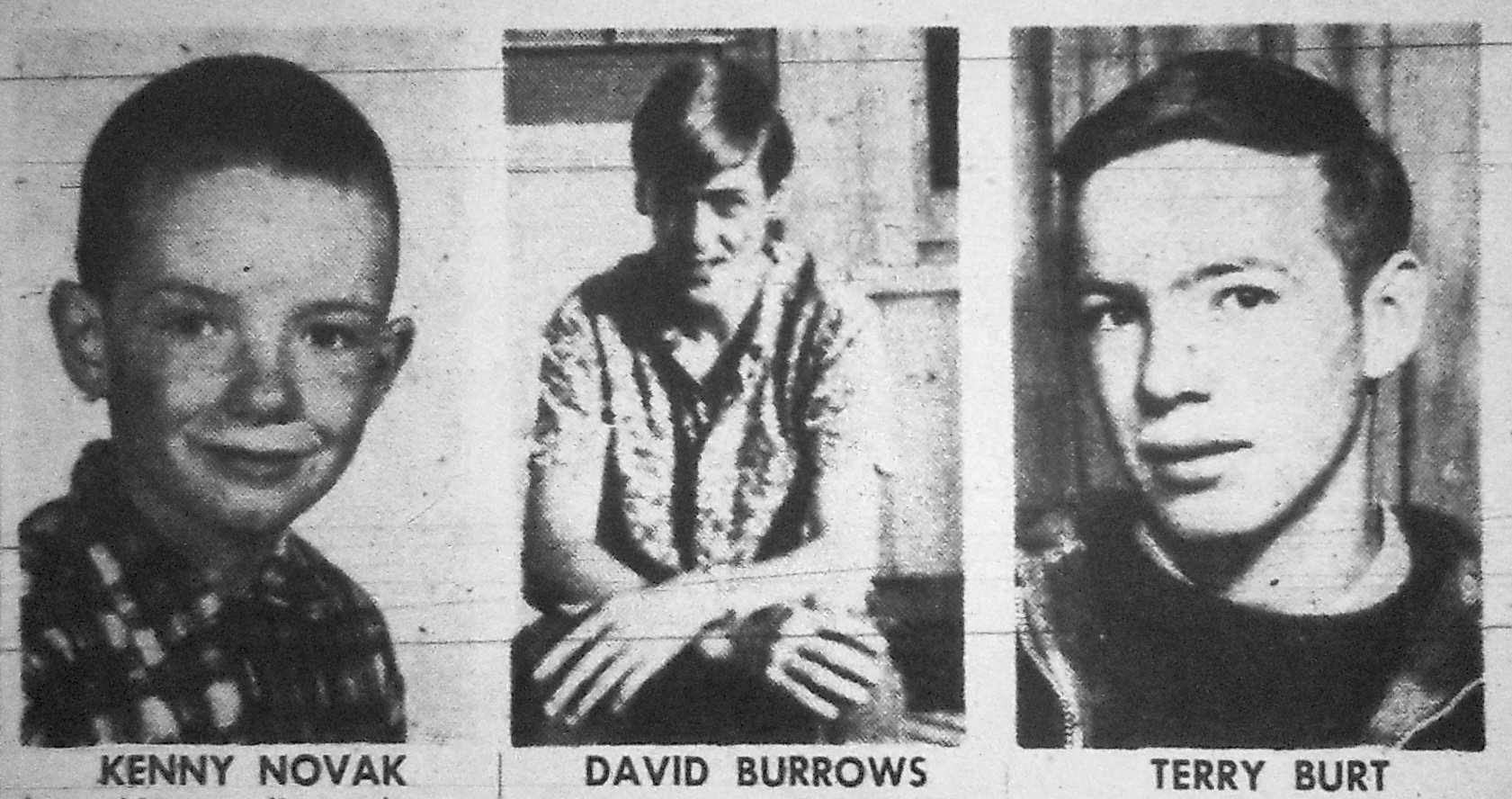

Canadian Mounties had determined the identities of the three youths.

The youngest victim was 15-year-old Kenneth Novak, who went by “Kenny”. He was his youngest of seven children—the baby of the family. The other two boys were 17-year-old David Burrows and 20-year-old Terry Burt. Terry sometimes went by Thierry, the name he had written on the label.

All three were residents of the large working-class town of Sydney in Cape Breton Island on the North East tip of Novia Scotia, a whole time zone away, which meant these boys were close to 500 miles from home. Their fathers, angry and afraid, traveled the same path the boys had taken just days prior, to identify their bodies.

Who were these boys?

According to Ken Jessome, the popular hangout spot for teens in Sydney, Nova Scotia was a two-block stretch from the Post Office to what they called “The Gym” (known as the Holy Redeemer Parish Center to the adults) where they’d play floor hockey and basketball, bowl downstairs in the basement, and attend the dances on Friday nights.

On those blocks, kids ruled the streets—bumming cigarettes, making plans, and chatting with friends. There may have been the occasional surreptitious swig of a flask, too.

“We were a pretty decent bunch, but we weren’t saints — we had our share of stupidity and badness. Bullying and sneakiness, irresponsibility and moral cowardice: they seem, to some degree or another, to be part of the adolescent journey.” Ken wrote.

The culture war of the mid-1960’s reached a fever pitch in the early 1970’s. It was an anti-establishment movement that extolled the virtues of free love, radical expression, and experimentation. Public support for the Vietnam War was waning, draft dodgers and ‘conscientious objectors’ were a hotly debated issue, and a line was being drawn between long-haired hippies and pro-war hawks.

Protest songs like CCR’s “Fortunate Son” and John Lennon’s “Give Peace a Chance” were playing on the radio.

In Sydney, the same cultural debates raged and the boys searched for answers and expressed themselves through music.

Terry Burt, 20 yrs old

Terry Burt was the oldest of the trio. He was 20 in July of 1970 and from Whitney Pier, a neighborhood in Sydney. He reminded Ken of John Lennon, sporting similar long hair and circle glasses. He was thoughtful and introspective, polite and wise—a gentle spirit searching for answers. Terry loved music, and like most young people in Cape Breton, the music of Jethro Tull, an avant-garde rock band led by an eccentric rock flutist.

He also loved his chopper—a motorcycle with the high handle bars, and drove it everywhere.

Ken wrote that after Terry had officially given up cigarettes, he would occasionally fall off the wagon—joking that cigarettes were poisonous drugs while sheepishly lighting up his own to smoke. Other than this vice, Terry seemed to take care of himself.

David Burrows, 17 yrs old

David Burrows was 17, and according to people who knew him, he didn’t change his appearance from junior high to high school. His appearance was more conservative than “hippie” like many of his counterparts. Apparently, David was growing out his hair—much to his parents’ chagrin—who threatened to kick him out until he got a haircut.

According to some, David was also a free spirit who wore his heart on his sleeve. Others who knew David chimed in with memories of him, calling him a well-liked and easy-going guy with a great smile. A woman named Janice wrote,

“We hung out together and skated together. He would visit my house. My Mom adored him... pretty sure she wished we would date. He was a hippie I guess, perhaps we all were... I'll always have a place in my heart for him.”

Kenny Novak, 15 yrs old

Kenny was described as tall and slender and had shoulder length light brown hair with soft curls that had a mind of their own and hid his youthful face. He was always flipping them back. Friends described him as sweet, energetic, and funny, yet contemplative and thoughtful. He was popular with girls and had a wide network of friends. He easily fit into any group. A friend named Karen said he wore a Burberry military style jacket in the winter and his army surplus jacket in the spring. His older brother Lorne, the closest in age to him of the 7 siblings, remembered that he had taken three years of Latin and was a bright kid.

Ken wrote about a memory another friend named Pat had of them both at a dance one night at the Gym: “A few of us had arrived early to put out the tables and chairs in return for free admission. It was about 9 pm, because the doors had just opened and Soul Sonny, the regular Gym DJ, was on stage getting ready to start the music:

I remember Terry was sitting by himself on the edge of the stage, having a smoke. People were just starting to drift in. Soul Sonny put on a rock song, ‘Mississippi Queen,’ that opens with cowbells, and Kenny jumped up on the stage and started dancing. Terry looked up at Kenny and burst out laughing. That’s the last time I remember seeing Terry. It’s a good last memory – Terry laughing with his friend and Kenny dancing.”

The boys hitchhike 500 miles from Sydney to Houlton, ME

It was summertime in Cape Breton, and the kids were out of school, and taking trips with their friends. On Sunday, July 5th, Kenny’s mother, Isabel, drove Kenny and his friend, 20-year-old Terry Burt, 90 miles up the coast to a beautiful Canadian National Park, called the Cape Breton Highlands where they stayed in a campground in Ingonish, likely spending time at the popular beach there. When his mother waved goodbye, she expected that he would make it home in about a week—hitchhiking—a common way to get around in 1970. Little did she know she would never see her son again.

According to Ken Jessome, another friend joined them there: Alan Crawley. He remembered hitchhiking to Ingonish to meet Kenny and Terry. It was his first experience camping, and he remembered how difficult it was to set up the tent and the metallic taste of cold beans in the morning for breakfast.

Shortly thereafter, 17-year-old David Burrows joined the group. Alan had never met him before. According to Alan’s account, David, for a reason Alan couldn’t remember, proposed the boys hitchhike to the states. There are rumors that they met some girls from Boston and DC while at Ingonish and they concocted a scheme to visit them on a wild 1,000 mile adventure. Three of the four boys decided to make the journey, but Alan turned down the offer to join and opted to head back to Sydney instead, perhaps saving his life.

Another small piece of the puzzle that suggested that this trip was a spontaneous choice was the fact that Terry made plans with a Sydney girl, Rose to see a local band, Pepper Tree at the “Sydney Forum” on Thursday night. She said that she went that Thursday and looked for him all night to no avail.

Unbeknownst to Kenny’s mother, the three US-bound boys returned to their hometown in Sydney within just a day or two of being dropped off in Ingonish, cutting their week-long trip short. They set off on their adventure before their families even knew they had left. David met up with a girl, Margie Burke, with whom he was close, to ask for her address, before they left Sydney. He told her of their plan and he wanted to be sure to be able to find her when they returned. She wrote down two addresses for him – one at her home and another in Halifax, where she might be visiting family later in the summer. She spoke regularly to David’s mother, and that’s how she learned of the boys’ plan of international travel.

The three boys hitchhiked 471 miles from Sydney to Houlton, ME, and along that trip, David gave Margie a call. She remembers it clearly. It was a sunny afternoon and the call was crystal clear, making her think that it was definitely not from a payphone – more like a house line. He said they were tired of the road, running out of money, and were coming home. Perhaps it was from the motel that they stayed at in Fredricton on the evening of Wed, July 8th.

Night of the tragedy

The Aroostook County Sherriff’s department said that the trio had crossed the border near Houlton without alerting the border patrol around 11pm on Thursday, July 9th, the last night the boys were seen alive.

The boys ended up at an ice cream shop near Drake’s Hill in Houlton, and as 21-year-old Royden Hunt was leaving with his friend Mike, Royden found himself saying yes when asked by a young man if he would give him and his 2 friends a ride down through town. The ice cream shop was only about a mile and a half from the Canadian border. He and Mike were leaving anyway, so why not, he thought. It was a nice night, about 70 degrees. Roy noted that the trio was young, maybe mid to late teens, and they looked a bit disheveled. Royden agreed, and all five young men hopped into his blue Pontiac car, the three hitchhikers stuffed into the backseat with their knapsacks.

During the car ride, the youngest, Kenny fell asleep. Long-haired Terry and David smoked 2 or 3 cigarettes each while chatting about their recent travels. Royden recalled Terry saying something about Washington DC and going to see a girl. They also joked that Royden shouldn’t worry because they weren’t carrying any drugs.

Around 11:45pm, Royden dropped them off at the Smyrna exit on the interstate, not far from where the train accident occurred. Royden dropped off Mike a little further down the road at his work – the Irving gas station in Oakfield, and then headed home to Island Falls, just a short drive further down I-95.

The boys thanked him for the ride and disappeared into the woods of Aroostook County, and what happened after that we may never know. The only thing we know for sure is that boys were struck on the tracks a little over a mile away from where they were dropped off.

Aroostook County sheriff rules it an accident

The earliest newspaper reports of this incident refer to it as an accident, as determined by local Aroostook County Sheriff, Darrell Crandall. Even before they knew their names, police concluded that the boys had chosen to camp on the tracks and were fast asleep when they were struck and killed by the train.

The autopsy report completed the following day further reinforced the police’s theory. It concluded the boys were killed on impact, and that they were alive before, ruling out the possibility of foul play in the investigators’ mind. Deputy Sheriff Socoby said that, based on the medical evidence, it was impossible the boys could have been placed on the tracks. Furthermore, he found it was impossible that if they were killed elsewhere that somebody would have moved and staged all their personal belongings with their bodies.

Could a train “sneak up” on you?

I wanted to understand how three boys could fall asleep on tracks and not wake up in time to save themselves from an oncoming train. Wouldn’t they wake up? The train conductor blew the horn. Surely if the rumble of the tracks didn’t wake the boys up a train’s horn would… right?

According to an article from The Philadelphia Inquirer, almost 1,100 Americans were killed in 2018 on train tracks. The majority being what is termed trespassers — in other words, pedestrians who are walking or sleeping on tracks.

I watched a video put out by The Rossen Report in 2016 on the Today Show that made me question what I assumed I knew to be true. It claims that trains are actually much quieter than we think they are, and said that oftentimes people don’t know they’re there until it’s too late.

According to an expert interviewed for the segment, it takes most trains at least a mile to stop after the emergency brakes are pulled. The video showed recent examples of young people accidentally killed by trains. Young people who were awake and standing.

The most unsettling example was an accident that killed 3 teenage girls in Utah taking group selfies on the train tracks. The train conductor saw them for about 12 seconds and blew the horn to no avail. Their ominous final photo from that day shows the oncoming train in the background seconds before impact. Couldn’t they hear the train?

The Rossen Report included an experiment to see if their reporter, could hear the train approaching. Standing in front of a train, the rumble you’d expect is much quieter than you’d think. The reporter didn’t hear the oncoming train until it would have been only a few seconds from impact, but once the train passed him, the roar was deafening.

It's a strange thing to think that such a massive piece of powerful machinery can be upon you with no warning.

Murder Theory

Despite the official ruling, doubts lingered. Why would three sound-minded boys choose to sleep on railroad tracks that are used daily by deadly trains? What if instead the boys had been killed sometime that night and their bodies were placed on the tracks…

All three boys were from the industrial, working-class towns near Sydney,—a region crisscrossed with railroad tracks. Kenny’s mother, Isabel, said her son “was sensible, and knew better than to sleep on the tracks.” Kenny’s father, Frank, was a steel plant diesel mechanic. Surely Kenny knew the dangers of giant machinery.

The distance between the rails was only 4 feet 8 ½ inches, and the boys were reported to be in between the rails, lying parallel to the tracks. For this arrangement to be possible, they would have had to been lying on their sides, spooning one another, huddled tightly together—an unlikely arrangement (especially for this group of teen boys). Moreover, they would be lying on the very uncomfortable track bed—tar-covered lumber beams and sharp granite rocks. Why not the soft earth in the nearby field?

Secondly, why wouldn’t have the boys moved in time, or at least stirred, showing some signs of life? Approximately one mile before the train struck the boys, it crossed Timoney Rd, a lighted crossing, where it would have sounded its very loud horn, perhaps 140 decibels, for 20 whole seconds, and it would have been audible, but distant, from the boys’ location. The train crew reported that they identified the sleeping bags from about 150 feet away and sounded the horn. At 40mph, that would be approximately 4 seconds of a blaring air horn plus the sound of the train itself—certainly enough to alert at least one of the three youths. But the railroad crew all reported no movement from the sleeping bags. There were even comments that the sleeping bags were zipped up all the way over their heads. Not only the sound of the train, but the light of the day could have awakened the boys. Sunrise was at 4:50AM that morning. They were struck around 7:00AM, 2 hours and 10 minutes after sunrise.

Third, there were things missing from the boys. No identification was found with their bodies. Perhaps the youngest, Kenny, at only 15, may not have been carrying ID, but certainly the other two —a 17 and a 20-year-old— both of whom drove motorcycles—would have had theirs with them. Also, there was money missing – only $5 dollars was found.

One of Kenny’s friends, Dan Smith, shared his story with Lorne.

“I was to go on this trip with Kenny. We were planning to pool some cash and source out “a buy,” state-side (in other words a substantial drug purchase), with the exception of David Burrows... he didn't partake. At the time, I was working part-time at CJCB (a Cape Breton radio station). I ended up being scheduled for work at that time and had to back out, but because of the initial plan, I hooked up with Kenny at the Casino to contribute $180.00 to the cause and off they went. I know—for a fact—that they had at least $500 or $600 between them, so I’m convinced—always have been—that they were murdered. As I told Lorne, I’m very much open to testify under oath with this information.”

The man who gave the boys a ride from Houlton, Royden Hunt, told Lorne that they had a roll of money with them and that they had been counting it in the back seat. What happened to it?

Lastly, police failed to do a simple forensic medical test. Police arrived within 15 minutes of the boys being struck by the train, and if they had taken core temperatures of the bodies, they likely could have answered the question on everyone’s mind: how long had the boys been dead? If they had in fact been killed by the train, their bodies would have still been warm. It was about 62 degrees that morning, and the human body’s core temperature is around 98 degrees – a 36 degree difference, and it take many hours for the body’s core to cool.

And suppose they were moved, how would their bodies have been transported? There are no paved roads that go to the spot where they were hit. The closest paved road is I-95, but it seems unlikely that the would-be murderers would have felt comfortable parking on a highway, even under cover of darkness, to carry out their plan. But on close inspection, I found that there is an unpaved 4X4 (Four by four) trail that runs parallel to the tracks that is accessible from Route 2, the road that they were dropped off on by Royden Hunt, which could have been used to transport their bodies. Also, where they found seems like a particularly good spot to leave a body—just around a bend in the tracks, in a place where the sun comes up over the trees around the time the train crew would be coming around the corner. Surely somebody with local knowledge may have known these things.

So, suppose that the boys were killed, what would the motive have been? Perhaps money? Perhaps the money was just an excuse to make an example of these long-haired hippie youths.

Lorne’s search for justice

A month after the tragedy, Lorne went to the US to visit the site. He remembers seeing tattered bits of sleeping bag still littering the field neighboring the tracks where his brother was found dead, and his death has remained fresh in his memory ever since.

Many of the important details that we know now have come to light because of Lorne’s tireless efforts to look under every rock to uncover the truth about Kenny’s death. Lorne was able to track down the original autopsies as well as the death certificates for the boys. He tracked down Royden, who gave the boys their final ride and was able to get him on the phone to tell what he remembered from that night more than 40 years ago.

Lorne and his allies have created a very active Facebook group that has become a clearinghouse for much of the information about this case, including newspaper clippings, maps of the areas, timelines, and even the autopsies themselves. Many friends who knew the boys have become members and have shared details that are nowhere else found. The comment history of the Facebook group is hundreds of pages long.

Lorne and his supporters have also created a petition which is addressed to the Aroostook County Sheriff’s office to reopen the investigation into the boy’s deaths. It has 2,800 signatures.

Though Lorne has made substantial progress, he’s had his share of roadblocks.

He’s looked into getting private investigators from Houlton to take his case, but they haven’t been interested.

Even within Lorne’s family, there is division. Some of his siblings, of whom there are 3 living, want him to let the case be, but Lorne will not be satisfied until he has answers. He wants the police case files from Houlton, which he has repeatedly requested, and he wants the incident report from the train company, B&A Railroad. He has yet to receive any of this.

What now?

Lorne created a memorial plaque for the boys. He made it himself—a thick steel plate with a welding bead spelling out the names of the boys and the date of their deaths. In summer of 2020, he had it installed on a rock ledge by the tracks so that the train crew could see it as they pass.

It has been 51 years since Lorne lost Kenny, and he still fights for him today, because Kenny is his brother, Kenny is his family, and family is forever.

Ken Jessome feels a duty to tell this story to right a wrong from his childhood. Though kids have limited power, Ken believes that he could have done more, that the community could have done more, for these young boys. His voice, heard through his writing today, betrays his own guilt from the past and proves that it is never too late to make a difference.

His writing has shined a light on this mystery and through the power of technology, a community, scattered in the wind, has reemerged, recollecting personal stories about the boys and the community that they all shared in Sydney.

We may never know what truly happened to Kenny, Terry, and David. We may never have the answers we wish we did. But their story lives on through the community who still remembers them and the community who still seeks the answers to the questions that haunt them.

If you are have any information about the deaths of Kenny Novak, David Burrows, and Terry Burt, I urge you to contact the Aroostook County Sheriff’s Office at 207-532-3471.

Links

Join the “SEARCHING FOR ANSWERS: the 1970 deaths of 3 Cape Breton Youth in Maine” Facebook page

Sign the petition to reopen the investigation

Connect on instagram @MurderSheToldPodcast

Click here to support Murder, She Told.

Terry Burt (center on red bike) with a group of motorcycle friends

Map of Smyrna Mills, ME, where boys last seen

Map where boys last seen (Bangor Daily News)

Where the boys were dropped off by Royden Hunt, Route 2 in Smyrna Mills, ME

Final page of autopsy (almost identical in all three autopsies)

B&A (Bangor & Aroostook) train engine

B&A (Bangor & Aroostok) train engine

Memorial Plaque, made by Lorne Novak in 2020

Sources For This Episode

Newspaper Articles

Various articles, from the Bangor Daily News, Cape Breton Post, Houlton Pioneer Times, The Gazette, The Ottawa Citizen, The Vancouver Sun, The Windsor Star, Times & Transcript, Times Colonist, written by Dean Rhodes, Ken Buckley, and various wire services.

Full listing here.

Online Written Sources

'Remembering a Mysterious Summer of ’70 Tragedy' (Cape Breton Spectator), 7/19/2017, by Ken Jessome

'Sleeping Victims: A Cape Breton True Crime Story?' (Lokol, your local everything), 6/6/2018, by Ken Jessome

'“An Unfortunate Mishap": Three Cape Breton Deaths' (Lokol, your local everything), 7/10/2018, by Ken Jessome

'Who Killed the Three Cape Breton Boys on the Tracks?' (Lokol, your local everything), 9/10/2020, by Ken Jessome

‘SEARCHING FOR ANSWERS: the 1970 deaths of 3 Cape Breton Youth in Maine’ Facebook page, various posts

Video sources

'QUEST FOR JUSTICE: The Cape Breton 3 (Interview with Lorne Novak)' (YouTube), 9/10/2020

Interviews

Ken Jessome

Podcast Sources

'The three cape breton boys on the tracks’ (Nighttime Podcast), 5/1/2019

'S1 E2 The Cape Breton Boys on the Track' (Anchor), 12/6/2019

Photo Sources

Various photos from online written sources, especially the Facebook group.

Credits

Created, researched, written, told, and edited by Kristen Seavey

Research, writing, photo editing support by Byron Willis